Medical examination

Background to, and purpose of, a medical examination

Together with the compilation of a thorough medical history and, as and when required, further investigations such as imaging scans or laboratory tests, a systematic medical examination forms the third pillar underpinning a diagnosis.

Whereas the medical history is concerned with and assesses the symptoms (as reported by the patient) of a condition, the medical examination is used to look for signs (that can be objectively detected) of disease, following on from the medical history. Positive findings (for example, a heart murmur) and important negative findings (for example, absence of a wheeze for somebody suffering from asthma) are equally relevant in refining the overall picture. It is sometimes said that there is an escalation from subjective (history) to objective (examination) to objective-quantitative (laboratory and other technical investigations) findings, and that these should be weighted accordingly. This is too simplistic a view – only all of the findings combined constitute the features of a particular condition in a particular person at a particular moment in time.

Below we describe the procedures and processes of a medical examination in non-emergency situations. The same principles and procedures apply for a medical examination in establishing a diagnosis and in preparation for surgery in a pre-operative assessment clinic.

In an emergency, these approaches to evaluation and assessment are not appropriate, instead internationally agreed protocols for dealing with emergencies are followed to quickly assess the situation and inform the most appropriate actions.

Obviously, the body area of the investigated pathology will be thoroughly examined.

However, the purpose of a medical examination is much broader than merely to focus on the symptomatic region: a medical examination is meant to give an overall impression and to put a localised set of symptoms into a more holistic context. This is achieved by systematically examining the various systems of the body in addition to the symptomatic region.

Below we describe the most common procedures in examining the various body systems (regions). The extent and nature of these examinations should be tailored to the individual, and this depends on the general health of an individual and, in a pre-operative assessment setting, the nature of the planned surgical procedure. A medical examination comprises a general examination and further systematic examinations by following a sequence – looking (inspection), touching (palpation), tapping (percussion) and listening (auscultation).

General examination

For a general examination, the patient must be comfortable, lying at about 45o and suitably exposed to allow complete examination of the chest and abdomen (see Figure 1).

When determining the general status, the following questions need to be addressed:

- Is the patient well or unwell?

- Is the patient orientated or confused?

- What colour is the patient? Pallor (pale skin) suggests anaemia, is there jaundice (yellowish skin) or bluish discoloration of the lips and undersurface of the tongue.

- What is the hydration status of the patient? Dehydration is recognised by a dry mouth with cool, poorly perfused peripheries, decreased skin and tissue turgor (elasticity), sunken eyes and a furrowed tongue.

Next, the hands may reveal tar stains from heavy smoking, peripheral cyanosis (bluish discoloration), clubbing (deformity of finger and/or toe nails; see Figure 2) as well as alterations in temperature of the hands and excess moisture.

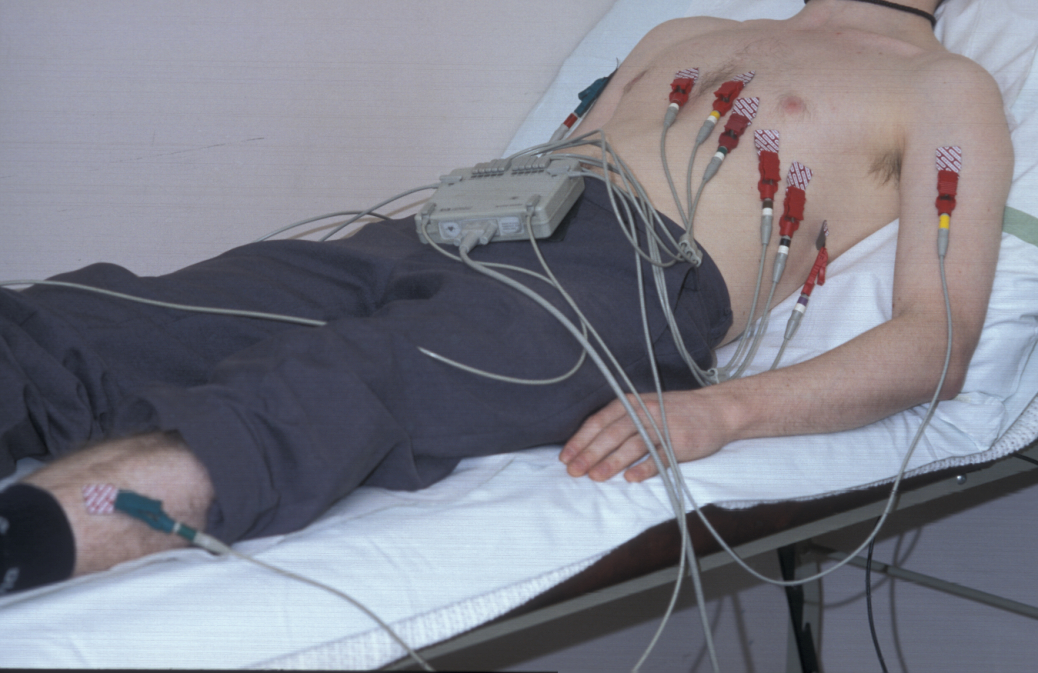

Working up from the hands, the radial pulse is taken, assessing the rate, rhythm and character of the pulse. Tachycardia (pulse rate above 100 beats per minute) may accompany pyrexia (fever), signify fluid depletion, or may simply reflect anxiety. Bradycardia (pulse rate below 60 beats per minute) occurs in patients on beta blockers or with certain cardiac arrhythmias (irrregular heart beat), but can also occur in young fit athletes. If an arrhythmia is suspected, it can be further investigated with an electrocardiogram, ECG.

The rhythm of the pulse can be regular, regularly irregular, or irregularly irregular. The character of the pulse can be weak and thready, or bounding after exercise or in the presence of a fever.

Another part of a general examination is to take the blood pressure (see Figure 4) and to take the temperature.

Systematic examination

Cardiovascular system

Inspection – general inspection may reveal corneal arcus (lipid deposits in the eye) and xanthelasma (lipid deposit in the skin around the eye), indicative of atherosclerotic disease, or clubbing (deformity of finger or toe nails) and central cyanosis (bluish discoloration) in patients with congenital cyanotic heart disease. The presence of central cyanosis indicates a reduction in the oxygen saturation of arterial blood and may be due to cardiac or respiratory disease, such as pulmonary oedema or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The jugular venous pressure is estimated (the jugular veins are the pair of large veins in the neck). The head is turned to the left looking for filling of the right internal jugular vein. A raised jugular venous pressure most commonly occurs in right sided heart failure and with fluid overload.

Palpation – the apex beat is the most inferior (lowest) and lateral (sideways) point where the heart can be felt beating. The normal position is the 5th intercostal space in the midclavicular line (see Figure 5).

The apex may be displaced inferiorly and laterally because of cardiac enlargement. In left ventricular hypertrophy (enlargement) the apex beat is more forceful than normal and is described as heaving.

Auscultation – of the heart looks for abnormalities in rate, rhythm and the presence of additional sounds in the cardiac cycle, using a stethoscope. Heart murmurs arise due to turbulent blood flow which can be due to regurgitation of blood through an incompetent or leaking valve, due to flow through a stiff or stenotic valve, or due to flow through a septal defect. Additionally, flow murmurs occur when there is increased blood flow through normal valves; such murmurs are common in pregnancy and anaemia.

Respiratory system

Inspection – may reveal signs of respiratory disease including finger clubbing, (often due to bronchial carcinoma), central cyanosis, laboured breathing, a cough or wheeze. The pattern of breathing may include respiratory effort, and the respiratory rate (normally 12-18 breaths per minute) may be abnormal. There may be asymmetry of chest wall movements; a diseased portion of lung leads to reduced movement on the affected side.

Palpation – the trachea (windpipe) is palpated by gently pressing the index fingers into either side of the sternal notch (the dip between the neck and the collarbone) feeling for deviation (this may be uncomfortable). Chest expansion is assessed by placing the hands around the ribs with the tips of the thumbs meeting in the midline at the xiphisternum (lowest part of the breastbone). The thumbs move apart with inspiration and the relative contribution of each side of the chest is determined. A similar technique is used when examining the posterior chest. Normal chest expansion is at least 5 cm.

Percussion – the normal percussion note of the chest wall is described as resonant. Percussion of the chest is performed by placing the non-dominant hand flat on the chest wall, with the fingers splayed and the middle finger positioned over the area to be percussed. This finger is pressed onto the chest and struck firmly with the tip of the middle finger of the dominant hand, with movement at the wrist. The anterior (front), lateral (side) and posterior (back) regions of the chest are percussed symmetrically, comparing sides at each level (see Figure 6). The sounds are described as resonant (normal), dull or hyper-resonant (both abnormal).

Auscultation – breath sounds are assessed by breathing steadily in and out through the mouth. Normal breath sounds (also called vesicular) are due to the transmitted sound of turbulent air flow in the larynx (voicebox), through the trachea (windpipe), bronchi (airways leading into the lungs), and lung tissue and chest wall (see Figure 7). The quality of breath sounds can be reduced in intensity by airflow limitation, for example in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Breath sounds become ‘bronchial’ when lung tissue becomes solidified by consolidation or fibrosis. This sound can be mimicked by blowing over the top of a glass bottle.

There may be additional breathing sounds, namely wheezes and crackles. Wheezes are musical, like a high pitched whistle, due to passage of air through narrow bronchi, and are characteristic of asthma. Crackles are non-musical sounds due to secretions (in which case they are reduced by coughing) or the opening up of collapsed small airways, usually in the lung bases, on inspiration (for example in pulmonary oedema). This sound is compared to the opening of Velcro.

Gastrointestinal system

Physical examination of the gastrointestinal system is confined to the mouth, abdomen and rectum. In order to examine the abdomen, patients should lie flat with their arms by their sides to ensure that the abdominal muscles are relaxed; nipple to knee exposure is required (see Figure 8).

Inspection – general inspection of the gastrointestinal system is used to look for evidence of malignancy, malnutrition and chronic liver disease. Signs include jaundice, palmar erythema (reddening of palms of hands), leuconychia (white nails), bruising and purpura, gynaecomastia in males and spider naevi (dilated small arterioles) on the arms, face and upper body.

Inspection is commenced from the foot of the bed, looking at the patient as a whole and at the abdomen for obvious asymmetry, distension, scars or herniae. Cutaneous striae are linear pink or white markings on the abdomen and thighs due to pregnancy (stretch marks), obesity, and Cushing’s syndrome in patients on long term steroids.

Palpation – the abdomen can be divided into nine regions to facilitate description. The right hand is used to gently palpate each area of the abdomen. Guarding is the term used to describe involuntary tensing of the abdominal muscles in anticipation of pain. Rebound tenderness, indicating peritoneal inflammation, is elicited by gently pressing on a region of the abdomen and then releasing the pressure, which causes the pain to increase. This can be simulated by coughing, particularly helpful in children.

Palpation aims to assess whether the liver, spleen and kidneys are enlarged. Palpation of the liver begins in the right iliac fossa (pelvic area): with the palm flat on the abdomen, the radial border of the index finger is pressed firmly inwards as the patient is instructed to take a deep breath (see Figure 9).

This is repeated moving the finger up at each breath. The smoothness of the liver edge, surface characteristics and any tenderness are noted. A common cause of liver enlargement is viral hepatitis, in which the liver is also tender. In cirrhosis, the liver is very hard and may be irregular (although in alcoholic cirrhosis the liver is often shrunken and impalpable). Secondary deposits in disseminated malignancy are associated with a hard, irregular liver surface.

The spleen enlarges towards the umbilicus (naval), and palpation is started in the right iliac fossa, moving up towards the left hypochondrium (upper abdominal region). The tips of the index and middle fingers of the right hand are pushed inwards and upwards on inspiration. Splenic enlargement occurs in a number of conditions, including glandular fever and leukaemia.

The kidneys are palpated bimanually in the loins, with one hand under the patient and the other on top, pushing the hands together to trap the kidney between them. Kidney enlargement may be compensatory after a nephrectomy (removal of a kidney), or due to obstruction, cystic disease, amyloidosis, myeloma or tumour. Generally an easily palpable kidney is abnormal.

Percussion – organ enlargement can be confirmed by percussion, proceeding from resonant to dull; the percussion note is dull over an enlarged liver or spleen, but remains resonant over an enlarged kidney due to the overlying bowel filled with gas. In the presence of ascites (fluid in the peritoneal cavity), fluid accumulates in the flanks, leaving resonant bowel floating centrally. To elicit ascites, percussion is commenced in the centre of the abdomen (see Figure 10), working towards the left flank until the percussion note becomes dull. At this point, the finger is kept in the same position and the patient asked to roll to the right. The fluid redistributes by gravity, and after a few moments the percussion note over the same area becomes resonant. This is known as shifting dullness (also an unkind reference to a group of students).

Auscultation – bowel sounds are due to peristalsis (contractions of muscles of intestines), commonly detected by listening over the abdomen with the stethoscope. Absence of bowel sounds occurs in paralysis of the bowel wall (known as ileus) - this is a fairly common post-operative complication or following opioid use. Bowel sounds are increased and tinkling in bowel obstruction.

Nervous system

Apart from these two tasks that belong in the maxillofacial task list, assessment of the nervous system includes:

- checking the peripheral nerves – checking the tone, power, reflexes, sensation and co-ordination of each limb assesses peripheral nerves;

- checking the orientation, intellectual function and speech, and any obvious neurological deficit, such as a facial palsy or hemiparesis. This examination requires co-operation and adjustmen to an individual’s problem, understanding, behaviour and intellect. If there is a suspicion of a dementing illness or confusional state, a short mental test may be in order.