Palliative & end of life care

We all need to learn to better accept our own mortality, rather than ignoring the one certainty in all our lives. Reflecting on and talking about death and dying does not kill us, but it may well help us to experience both a better life, and end of life, whenever or however this may happen.

In recent decades, we seem to have lost touch with some of the fundamental certainties of a human life. This includes death. This is in great contrast to the 15th to 17th centuries in Europe, when beautiful books were written about ‘ars moriendi’, the art of dying – with as much emphasis on the end of life as on ‘ars vivendi’, the art of living (well). In the middle ages in Europe, death was ever present in daily life, through wars, the plague, other epidemics and natural disasters. The emphasis of ‘ars moriendi’ was much inspired and guided by Christian faith and beliefs, and related forms of spiritual support. Triggered by need (in the absence of anything resembling modern western medicine), back in those times many such books were written for priests to help them provide support for the dying. The period of enlightenment and later, in the 19th and 20th century, social revolutionary movements reduced spirituality in the Western cultures. However, our drive to associate meaning to matters we cannot control or explain seems to be as deeply rooted in the Western culture as in any other culture on this planet.

Perhaps in the 21st century it is time for all of us to think about a contemporary version of ‘ars moriendi’. There are no simple answers, and certainly none that would be valid or relevant for every person. However, recalling some considerations and asking questions rather than aiming for answers may be the best approach to eradicate an unhelpful taboo. Eradication of this unhelpful taboo should include establishing much more open and accepting discussions and attitudes with regard to end of life, whether self-controlled, assisted in some way or uncontrolled. The latter is often seen by some as ‘natural’ although in most instances the influence of medication clearly renders that adjective dubious.

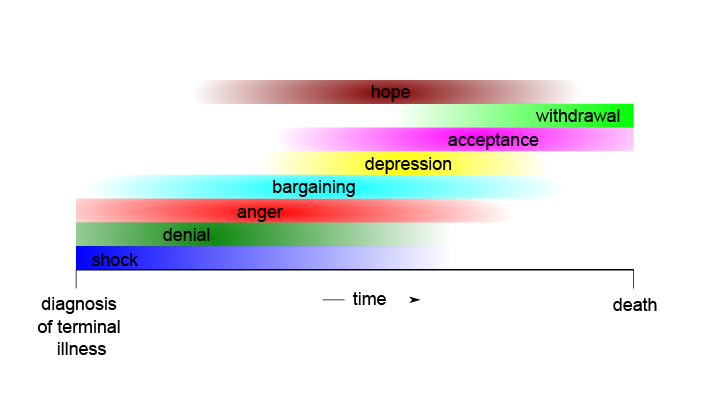

Some 50 years ago, the psychologist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross collated a large number of terminally ill patients’ discussions and reflections about death and dying (patient-centred research was quite revolutionary at that time). She summarised the overall trends from this rich material about death and dying as five ‘stages’ of grief (as a slightly artificial and overlapping set of categories, however, highlighting that the experience of dying is not solely one of grief), with some common patterns of developments over time (Figure 1).

Unsurprisingly, the initial phase comprises shock and denial, often followed by anger and/or bargaining. Sometimes a phase of depression precedes a prolonged period of increasing acceptance, and finally, withdrawal. Overwhelmingly, a general feeling of hope seems to be a broad theme throughout the entire experience. In clinical practice this reflects one of the ‘absolutes’ – one must never take away hope.

Some of Kübler-Ross’s observations chime with more recent research carried out in hospices – where a ‘good death’; as sometimes described idealistically by professionals, often seems to be quite out of touch with the actual feelings of many patients. Often there seem to be professional expectations that enabling a ‘good death’ is strongly associated with advocating acceptance and continued reflection. However, coming to terms with the end of one’s life and the fundamental interruption this means for the dying, alongside the continuity of life in general but in one’s own absence, there is undoubtedly a strong sense of vulnerability.

For example, in this situation many find comfort in the continuity of the banalities of one’s life, from watching one’s favourite soap opera, to indulging in one’s favourite junk food, to celebrating all kinds of everyday habits of a lifetime. This may well be interpreted as a form of continued denial. However, there is nothing wrong with insisting that a lifetime’s habits will simply continue until the end – perhaps this should be taken as a strong message of resilience: most parts of our lives are full of banalities, why should that be any different at the end of life?

This can also be an expression of the ‘somebody’ we still are at the end of life – despite the constant and urgent reminders of a failing body that all our existence depends on it, and on the support by others.

Some 30 years ago, the essayist Susan Sontag outlined some thought-provoking and useful observations. She criticised the prevalence of metaphor in all things disease and death, stating that the ‘healthiest way of being ill is one most purified, most resistant to metaphoric thinking’. Some metaphors are really not helpful, such as describing illness as a battle that one invariably is going to lose at some stage, thus qualifying a patient as a loser. Unfortunately, this concept is regularly misunderstood by carers, friends and family, often meaning well in describing someone as a ‘fighter’.

Similarly, military metaphors carry the danger of transforming the relationship between medical professionals, disease and patients into a muddled perception in which the patient is depersonalised, and simply the owner of a body that is the battleground to fight pathogens or disease. Military metaphor has largely been retired in recent years, although another metaphor, describing illness as a journey often replaces it.

Another common set of metaphors in relation to the end of life is borrowed from economics. For example, phrases such as ‘drawing the balance’, or ‘closing accounts’ are commonly encountered. We need to ask ourselves for whom metaphors are meant to be useful – for the dying person, for their nearest, for carers, for professionals? Why has everything related to death and dying become mystified and elevated? The use of metaphors should not be necessary – why do we not just spell things out as they are (for example, ‘cancer is just a disease’), why can’t we get ourselves to talk about somebody dying and instead refer to somebody passing away.

Sontag also observed that ‘master illnesses’ that change over time are the conditions most likely to be associated with unhelpful metaphors. For example, tuberculosis was the ‘master illness’ of the 19th century, cancer the ‘master illness’ of the 20th century, and many forms of dementia are likely to play this role in the 21st century.

The difficulties with reaching the limits of what we can express adequately in words are most probably related to our feelings of immense vulnerability when faced with pain, suffering, and the invariably finite nature of our lives. Therein may also lie the reasons that for many the language of music is deeply comforting. Music can be a powerful way to express, experience and overcome overwhelming feelings of negativity.

Some recent neuro-science studies present and support an interesting hypothesis that our brains may actually actively try to shield us from acknowledging our own mortality. This is despite the self-evident truth that we will die at some point. The brain’s decision-making mechanisms are thought to function like a prediction-based machine. These mechanisms face serious difficulty when presented with the need to predict disruption, nothingness – death – and may be the cause of fear of death. It has been speculated that this fear might be so powerful that humans could be too terrified to risk procreating. Hence, it may make evolutionary sense if humans’ brains somewhat negate our awareness of death and disconnect us from rational perception of reality in this regard. However, how the exact mechanism underpinning this down-regulation of our own-death awareness is manifested at a cellular/neuronal level is not yet understood.

The limitations of verbal communication impact and shape end-of-life care and support in so many different ways. Take well-meant attempts at providing consolation. The term ‘consolation’ has some negative connotations (a consolation prize – who would want to be up for that, in our remorselessly competitive society?). What consolation can words offer to somebody who lost the love of their life after decades of a shared life, or to somebody who will never see their children grow up. Consoling somebody is such a challenge because it forces everybody to accept our limitations and our losses. How can one trace (some) meaning for somebody else’s suffering and support their life to be as good as it can be? The art of consolation used to be a central theme of philosophy, in times long gone (Cicero and Seneca (letters to console widows) famously wrote about it) but now has, more or less, vanished from that discipline, mostly silenced by ever present medical treatments and technologies. All this makes it ever more difficult for all of us to acknowledge the realities of irreparable losses and grief; the impossibilities of consolation where there is none, and the acceptance that grief is not a disease but a part of human life.

Enhancing the technical abilities of medical care beyond it being simply an engineering-like discipline, requires us to remember some of the relationship between hope and resignation. It is all too easy to associate therapeutic options with hope, and consolation with resignation. There is no such binary distinction. Modern medicine has undoubtedly wiped out much suffering for mankind, but sometimes becomes the victim of its own successes. The successes of modern medicine in themselves represent a form of revolting against the passive acceptance of suffering, against the virtues of humility, reconciliation and submission as preached by most religions. It is not without reason that in the past people feared being buried alive, while nowadays many fear being kept alive for too long. Difficult questions too for the medical professions. When and what is too much? Who is to decide: legal paragraphs, patients, carers, doctors, economic circumstances? What behaviours do we consider to be in line with dignity? How can false hopes and illusions be avoided?

Perhaps we need to rethink some of our concepts of consolation and consider broader terms of support. Remaining silent together can be an enormous source of comfort and support. We should be more confident and not be afraid of doing or saying the wrong things. Support and care can take so many forms, a hug, a piece of cake, the mere presence of another individual – all just the opposite of indifference in the face of the most fundamental existential vulnerability we will all, sooner or later, experience. We should simply try to live life as best we can, and not exclude death and dying from our lives, our thinking and our communication with others.