Damage

Contents

Types of soft tissue injury

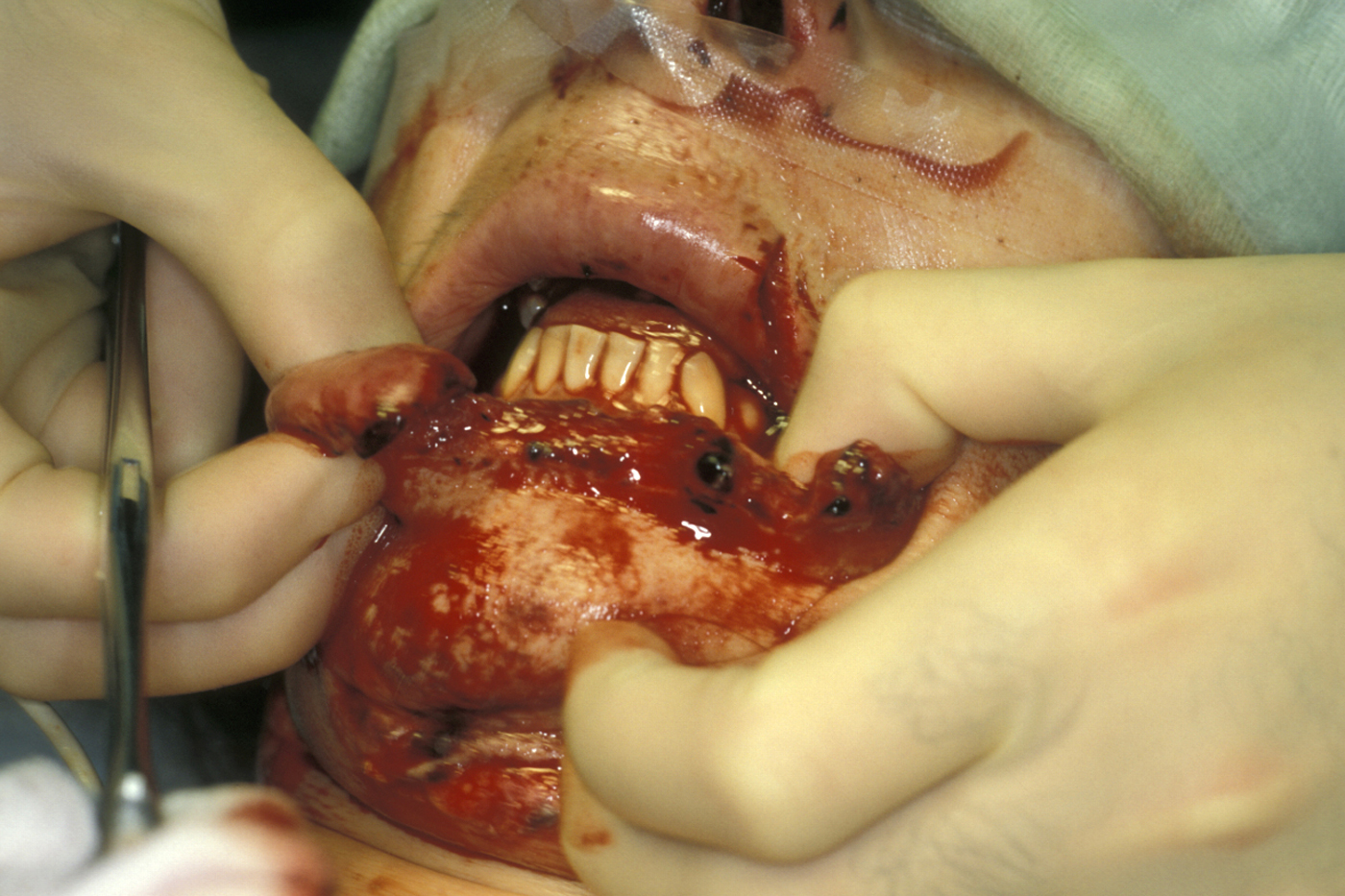

Soft tissue injuries may be divided into several types, these types being roughly indicative of the mechanism of injury. There may be some overlap between types of soft tissue injury or they may be found in combination (see Figure1 for an example).

Abrasions

Abrasions are caused by the force of an object rubbing on the surface of the skin. This results in detachment of the epidermis (the outer skin layer) and a ‘raw’ flat wound. The epidermis may be partially detached, heaping towards one side of the wound (following the direction of the blunt force), or totally detached leaving a raw surface. Most abrasions will scab over and re-epithelialize with minimal scarring provided there is no superinfection.

Contusions

These are bruises which occur due to rupture of blood vessels subcutaneously (under the skin) or deeper within tissue. The vessels rupture as a result of blunt trauma, releasing small to large amounts of blood into the tissues. The area of bruising will invariably be larger than the area of contact with the object causing the trauma. There may also be abrasion (see above) or laceration (see below) of the skin at the site of bruising. Contusions tend to resolve over a varying course from weeks to months, depending mainly on the extent of release of blood into the tissues. This is obviously influenced by drugs (aspirin being the most common) or conditions promoting bleeding.

Lacerations

These are splits in the skin and underlying tissues due to blunt impact, crushing the tissues over a site of bony prominence. The blunt trauma causes tearing of the skin, subcutaneous and deeper tissues, whilst blood vessels and nerves deeper in the wound may stay intact (see Figure 2 for an example).

There may be associated abrasion and contusion injuries (see above) at the site of laceration.

Incised wounds

These are ‘clean’ incisions through the skin and deeper tissues, caused by a sharp instrument or object such as a knife or broken glass. Nerves and blood vessels within incised wounds risk being partially or completely severed. Often these wounds are the result of an alleged assault, although some neck wounds may be self-inflicted. Although it is common to misuse the terms ‘laceration’ and ‘incised wound’, it is important to understand the practical difference between incised wounds and lacerations due to the increased risk of injury to underlying vital structures.

Avulsion

In an avulsion injury, tissue at the wound site may be displaced from the underlying tissue layers yet still partially attached (avulsion flap or ‘partial’ avulsion; see Figure 4) or may be totally detached from the wound site (complete avulsion).

Haematoma

A haematoma is a collection of blood within the soft tissues. A volume of blood released into the tissue, with no ‘break’ in the tissue to allow further escape, may collect to form a haematoma. In trauma this usually occurs when a blunt force ruptures one or more veins, releasing blood into the tissue spaces. The blood release tends to be self-limiting because, with no escape route, the tissue is limited in its capacity to expand which causes an increase in pressure within the collection. The pressure increase may reach the point where it compresses the vessel and resists further blood release (tamponade). Evacuation of a haematoma, therefore, may carry the risk of recommenced haemorrhage (bleeding). Haematomas may also form in areas where the tissue layers have been separated, creating ‘dead spaces’ for blood to pool. Haematomas, being stagnant collections of blood, are at high risk of infection.

High Velocity Missile

Injuries caused by a high velocity object, such as a bullet or shrapnel (which may include biological – human – body parts), may produce any combination of the above wounds. In some cases the damage superficially may appear minimal whereas deeper structures have sustained much more damage. In other cases, such as a close-proximity shotgun wound, large quantities of tissue may have been completely avulsed. In missile injuries the degree of damage is very dependent on the energy expenditure at impact. Small pellets from a distance at low speed will penetrate the skin but cause little underlying damage and are often impossible to recover (see Figure 5).

Larger pellets (for example high velocity airguns (for which a Firearms Certificate is required in the UK)) can penetrate significant distance and present an infection risk. Bullets create damage directly related to the degree of energy transfer, usually associated with composite tissue loss. Contaminated shrapnel containing body parts, such as that produced by suicide bombers, may also create the risk of microbial contamination (particularly hepatitis B or C, HIV or prions (small, infectious disease-causing proteins)). High velocity wounds may be self-sterilized at the point of departure from the weapon but can introduce virulent and unusual contaminants from victims’ clothing which can be contaminated to varying degrees (battlefield in comparison to civilian). In general, bullets cause tissue damage by laceration or crushing, shock waves and cavitation.

Assessment of wounds

History

The key questions to be answered are the following:

How and where did it happen? The cause of the wound must be identified. For example, if caused by a sharp object, deeper structures within the wound are more likely to be injured. If a weapon has been used, as much information about the weapon (including whether or not it broke in use) as possible should be obtained. If the wound was caused by broken glass, there is reason to suspect that the wound may contain fragments of glass (see Figure 6). Human or animal bites (or fragmented body parts in the case of explosions) indicate a high risk of wound infection, or indeed systemic infection (e.g. hepatitis B or C, HIV, rabies).

The location of the traumatic event is also important because it may provide further information. A wound sustained by a cyclist in a road traffic accident may contain gravel. A wound contaminated by soil carries an increased risk of tetanus (bacterial infection, though rare in the UK because of well-established vaccination programme; see below).

When did it happen? The older the wound, the more likely it is to become infected. Wounds that are more than 6 hours old are often assumed to be infected.

What is relevant in the medical history? The medical history will influence the treatment. Whilst a healthy young person may be treated uneventfully, a person who is taking warfarin (an anticoagulant, ‘blood thinner’) will have an increased bleeding time, and a patient who is immunocompromised may require antibiotic prophylaxis.

Important points raised in the medical history include:

- allergies (Latex, dressings, antibiotics, anaesthetics and so on)

- current medication (anticoagulants, antibiotics, steroids and so on)

- complicating medical conditions (diabetes, haemophilia, HIV and so on)

Tetanus status? Wounds considered to be prone to tetanus infection include:

- wounds with evidence of infection

- puncture wounds / stab wounds

- wounds contaminated by dirt / soil (common hosts of tetanus bacteria)

- old wounds (> 6 hours)

- wounds with necrotic tissue.

Immunisation with tetanus toxoid (+/- tetanus immunoglobulin) is required if a patient has not received a tetanus booster within 10 years or has never been immunised.

Clinical Examination

Notes should be made of

- the site and type of wound

- the size, shape, and depth of wound

- any tissue loss / avulsion

- the state of deep structures within the wound (nerves, vessels and so on)

- the condition of the wound (clean, dirty, infected, areas of necrosis and so on).

- the presence or suspected presence of foreign bodies.

A photograph or diagram can be useful to illustrate type and location of wounds; once the wound is photographed it should be covered with a sterile dressing and not further exposed until formal closure can be performed.

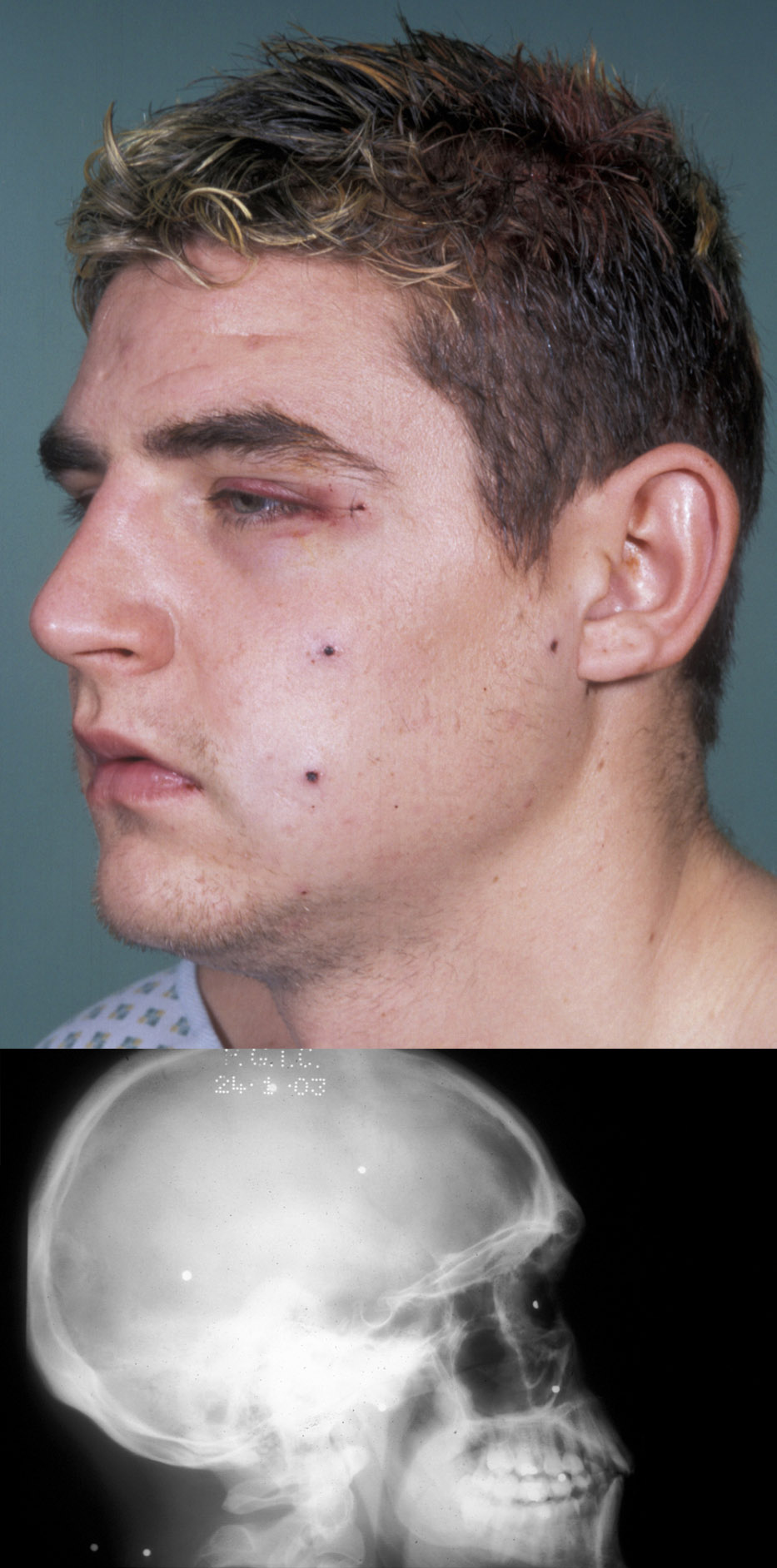

Special investigations

For the most part these are limited to plain X-ray radiographs, either to exclude underlying bony injury or the presence of a foreign body. Swabs for culture and sensitivity of contaminated or frankly infected wounds are probably worthwhile even though treatment will be started with ‘best guess’ antibiotics right away.