Dysplasia

Oral mucosal lesions associated with dysplasia

Leukoplakia

Oral leukoplakia (according to the World Health Organisation definition) is a white patch or plaque that cannot be characterised, clinically or histopathologically, as any other disease. There are a number of possible causes for white patch oral mucosal lesions and similar looking such lesions are quite common. Leukoplakic patches can appear in all areas of the mouth but the side of the tongue and the floor of the mouth (see Figure 1) are common locations. Leukoplakic patches come in a range of appearances and may be completely asymptomatic or cause symptoms. The overall risk for leukoplakic patches to become malignant has been quoted as 2 to 8 %.

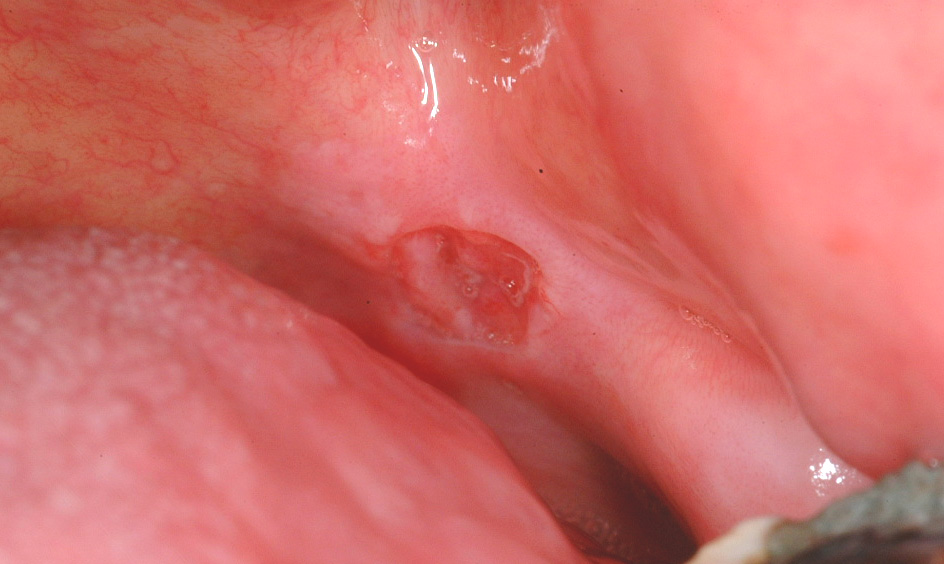

Erythroplakia

Erythroplakia is defined as a red patch (see Figure 2) that cannot be diagnosed as any other lesion. Erythroplakia is less common than leukoplakia but tends to display more severe degrees of dysplasia as well as a higher overall risk of malignant transformation; the overall risk has been quoted as 14 to 67 % (see below), and approximately 40 to 50 % of erythroplakic patches have high-grade dysplasia or carcinoma in situ present. The most common sites for erythroplakia are the floor of the mouth, tongue and soft palate.

Erythroleukoplakia

Erythroleukoplakia (also known as speckled leukoplakia) is the third of the oral mucosal lesions commonly associated with a risk of malignant transformation (see Figure 3). Speckled leukoplakia is an intermediate risk for malignant transformation.

Submucous fibrosis

Submucous fibrosis is a progressive lesion forming bands of scarred tissue (fibrosis) beneath the mucosa (see Figure 4). Submucous fibrosis is associated with epithelial dysplasia and a quoted risk for malignant transformation of approximately 5 %. The strands of scarred tissue (fibrosed bands) can lead to severe trismus (difficulty opening the mouth). Submucous fibrosis is strongly associated with chewing habits of areca nuts, gutka and betel – common on the Indian subcontinent.

Lichen planus

Lichen planus is a chronic autoimmune disorder of the skin and often affects the oral mucosa as well. It usually shows characteristic streaks or strands of white keratosis (see Figure 5). Lichen planus is sometimes associated with epithelial dysplasia, a so called lichenoid dysplasia. Of the fairly low malignant transformation risk (the incidence is approximately 1 to 3 %), the majority of cases is due to lichenoid dysplasia. It is important to note that the real risk of transformation of lichenoid dysplasia and erosive lichen planus warrants intervention whereas reticular pattern lichen planus that is symptomless doesn’t need anything in the way of intervention. This is fortunate given how common that condition is.

Other lesions associated with malignant transformation

Other oral lesions associated with malignant transformation include:

- chronic hyperplastic candidiasis (rare form of otherwise common oral fungal infection with typically candida albicans which may lead to persistent white lesions, even after treatment with antifungal agents; most commonly observed in conjunction with heavy smoking habits; such lesions have been reported to be associated with an increased risk for malignant transformation);

- sideropenic dysphagia (also known as Paterson-Kelly or Plummer-Vinson syndrome; a rare genetic iron-deficiency anaemia condition, leading to dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) and painful glossitis (a raw appearance suggestive of inflammation of the tongue); known to be associated with an increased risk for malignancy developing in the oral cavity, oesophagus (gullet) and hypopharynx (part of the throat linking to the gullet));

- dyskeratosis congenita and epidermolysis bullosa (two rare hereditary conditions affecting males; white patches on the back of the tongue may develop, similar in appearance to leukoplakia; malignant transformation of such patches has been reported in the literature);

- discoid lupus erythematosus (a chronic autoimmune condition; has been associated with lip cancer rather than cancers of the oral cavity);

- actinic keratosis (a condition of the skin, caused by long-term and/or intense exposure to UV radiation (sun light); also affects the lip, especially the lower lip (also known as farmer’s or sailor’s lip) and may transform to lip cancer).

Some general aspects of dysplasia

Grading and progression

Great caution has to be used when defining ‘premalignant lesions’ which affect the epithelial cells (the cells making up the lining of the mouth and other body cavities). The implication is that this can lead to and will often precede the most common form of oral cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, which originates from epithelial cells. This would be a useful, simple, understandable sequence of events which would enable, in fact mandate, early intervention to address every dysplastic lesion. Unfortunately (or arguably fortunately as they are so common) it’s not true.

There is some evidence:

- individual cases, where over time dysplastic tissue gradually undergoes malignant change;

- both leukoplakia and erythroplakia have been observed in the margins of confirmed oral squamous cell carcinoma;

- some typical changes in morphology as well as cytology are common between the premalignant lesions and established epithelial malignancies;

- some typical genetic and molecular fingerprints of invasive oral cancers are also found in premalignant lesions.

The fundamental problem centres around definitions of mild/moderate dysplasia and whether these histopathological conditions, whether or not they are clinically obvious as white or red patches, actually progress or are static or even spontaneously resolving.

Severe dysplasia is characterised by increasingly more severe levels of abnormality at cell and tissue levels. Whereas considerable controversy exists as to what exactly defines mild and moderate dysplasia and whether it is possible on histopathological grounds to meaningfully predict progress, severe forms of dysplasia, where in particular the characteristics at cellular level become increasingly abnormal, is a condition where greater consensus exists. In fact, some pathologists will argue that there is no, or hardly any, distinction between a severe case of dysplasia and a carcinoma in situ (an early form of establishment of a malignant epithelial lesion). Such blurred boundaries between developmental stages are illustrated in Figure 6.

Such a model of a perfectly orderly progression over time may well suggest that it is straightforward to assess the stage of the process and then select the most appropriate treatment option(s) accordingly. Unfortunately, matters are considerably more complicated. For example, there seems to be no direct correlation between the severity of the dysplasia and the risk of a malignant transformation of the lesion. Location of the lesion, environmental factors (smokers / non-smokers), age, diet and many more factors all contribute, making it difficult to predict the most likely course of events (and time scales of developments). It is more telling to observe how lesion and dysplasia evolve over time, rather than just thinking about the severity of the dysplasia as the only determining factor.

Many lesions with mild to moderate dysplasia never progress to a malignant condition. Even some cases of severe dysplasia may not progress. One possible explanation for this observation is offered by genetics, known as the two-hit hypothesis. It is mostly down to specialised genes, tumour suppressor genes (for example gene p53), to protect against the development and establishment of malignant cell lines. The chromosomes that carry all the necessary information are present in pairs in our cells, so there is always one back-up copy if one copy in one of the chromosomes is damaged by some kind of mutation and no longer provides an active tumour suppressor gene. As long as the second copy of the gene is not knocked out by another mutagenic event, cells and body continue to function normally and prevent malignancy from developing.

It is not surprising that the management and treatment of premalignant lesions can be controversial. The approaches vary considerably and range from ‘wait and watch’ policies all the way to far more aggressive policies that advocate the excision of all premalignant lesions wherever possible. It will be undoubtedly helpful if, in the future, better predictions will become possible based on grade and type of dysplasia than is currently possible.