Facial skin cancer

Irrespective of the type of malignant skin lesion (BCC, SCC or melanoma), the strategy for surgical removal is similar for all types with only minor differences (for example regarding margins of excision). The major determining factors about the best surgical resection and repair strategy are size and location of the tumour and risk of metastases.

Many of the general considerations described below are also relevant for the resection and repair of benign lumps and soft tissue wounds from trauma.

Excision of all skin cancers involves the deeper tissues as well as peripheral skin around the lesion, and this is of great significance in the head and neck region. Deep excision on the trunk or legs is straightforward as the subcutaneous layer of fat is considerable and will allow excision margins to be easily achieved without involving important nearby structures. This is not the case on the face, scalp or neck where margins of excisions will be affected by the close proximity of vital structures. These include the facial nerve, the eye and free margins (such as the eyelids), the lips and the alar rim of the nose. Another limitation is the limited depth of tissues available for excision such as on the scalp. Achieving an adequate margin of clearance around and beneath a tumour on the face may involve a smaller than recommended margin in order to preserve important structures and minimise aesthetic damage. It is, however, not sensible to plan an excision which will leave a macroscopically positive margin.

The majority of skin cancers on the head and neck may be surgically treated under local anaesthesia with or without sedation. A smaller group (about 30 % in major units) will require general anaesthesia for the surgery and reconstruction.

Repair of the surgical defects

Excision of a lesion unavoidably leads to surgical defects. Depending on size and location of the defect(s), there are a number of options in healing the defect(s). These include:

- Healing by secondary intention (no repair)

- Primary closure

- Local tissue transfer with random or axial flaps

- Skin grafting

- Remote tissue transfer with free flaps

A particular reconstructive technique may offer a clearly superior result, but if not the simplest choice is usually the best one.

Below we only discuss general aspects of healing by secondary intention (no repair), briefly comment on primary closure (more information about options and techniques is given in the sections dealing with the treatment and repair of trauma wounds) and finally discuss in slightly more detail surgical repair techniques involving local flaps. The latter techniques are of particular importance in the treatment of facial skin cancers.

Healing by secondary intention (no repair)

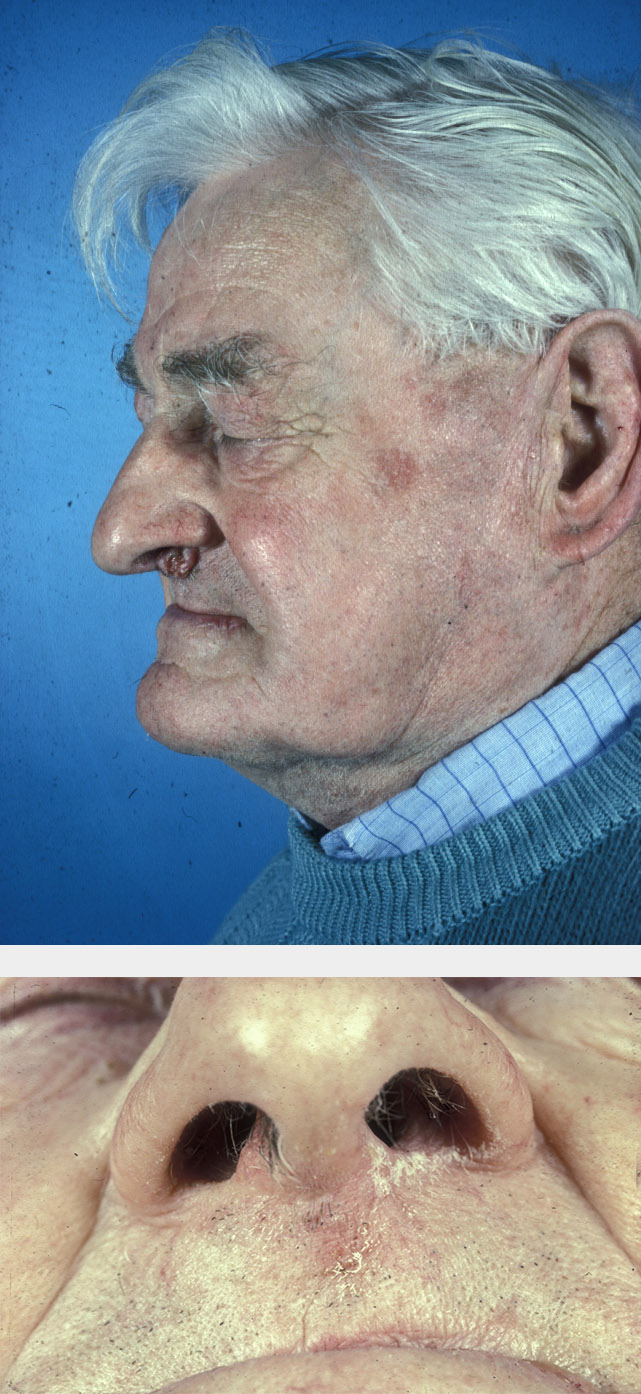

It has been shown that secondary intention healing can give excellent functional and cosmetic results, particularly if used for small defects in concave regions. This technique may also be useful in larger areas where contraction of the wound during healing is not cosmetically or functionally important. The longer healing time, increased wound care and poorer cosmesis must be taken into account when judging the appropriateness of this technique (see Figure 1 for an example).

Primary closure

Primary closure, for example by various suture techniques, allows quick reconstruction, rapid healing and a linear scar and is often the simplest reconstructive approach. If the technique can be accomplished without significant tension across the wound and with the suture line lying in the lines of relaxed skin tension or favourable skin line, then this approach may well be the best available.

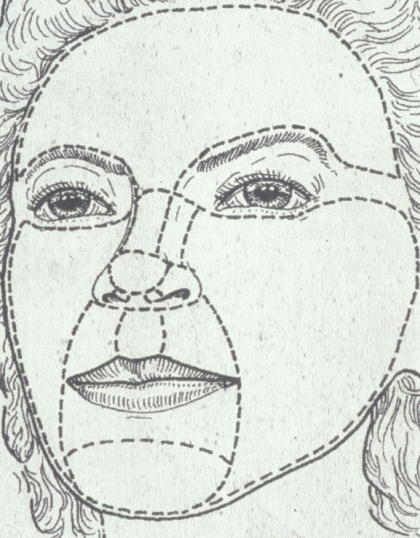

Any distortion of free margins or an anatomical subunit within the face, as well as the creation of long linear lines of poor aesthetic appearance would be an indication to consider another reconstructive option. Figure 2 outlines the (symmetrical) cosmetic units of the face.

With primary closure (and other techniques) it is important to keep in mind the stages of wound healing and the physical changes that will occur with time after the surgery: improvement will be slow as the wounds heal and the scars develop and mature over a period of about one year (there is an old proverb in German: ‘Die Zeit heilt alle Wunden’, meaning time heals all wounds, but indirectly pointing out that patience is required).

Local tissue transfer with random or axial flaps

A local flap is tissue from an adjacent area of surplus tissue (such as skin plus subcutaneous fat) that is moved such that it covers a surgical defect in such a way that still allows closure of the donor site. Flaps carry their blood supply with them, either from an identified major blood vessel (an axial flap) or randomly from multiple smaller blood vessels (a random flap). Local flaps offer significant advantages in facial reconstruction. Disadvantages are that flaps require additional incisions, and tissue movements can distort skin and may lead to increased complications. These flaps certainly require greater surgical skill, knowledge and practice. Potential disadvantages of local flaps are more than compensated for by their advantages:

- they can cover bare bone, tendon and cartilage

- tissue bulk can be restored, with similar tissue

- avoidance of distortion of free margins within the cosmetic subunits

- frequently aesthetically superior

When assessing a skin cancer for repair, the site and the resulting defect that will occur following its excision have to be thought through. The surgeon draws on the patient with a skin marker pen (before any local anaesthetic is given – it distorts the tissues) first the visible extent of the tumour margin and then the surgical excision margins. This gives both the surgeon and the patient a visual impression of the defect and clarity regarding the procedure.

Some of this planning may be initially disheartening because of seemingly excessive cut lines and large defects and flap. Documentation and photographs of medium and long term results for similar lesions and procedures will help to pick up the spirits.

Perhaps even more importantly, an understanding of the ideas and basic principles of using local flaps for facial reconstruction provides a good grasp of the likely reasonable functional and aesthetic result, as well as giving confidence and tolerance of such procedures for patients. With this in mind, we next discuss some basic principles of raising and moving local flaps.

Design of local flaps should take into account the natural facial lines, junction lines between cosmetic units (see Figure 2, above) and the lines of relaxed skin tension. Placing the resultant scars in these lines achieves camouflage wherever possible. An irregular pattern of scars is often less noticeable than a long linear scar and local flaps allow reconstruction with adjacent tissue of similar colour, texture and thickness.

Figure 3 represents the concept of reservoirs of facial spare tissue. Each individual varies, but the temple, cheeks, jowl, nasolabial area and glabella (the area between the eyebrows, above the nose) are characteristic reservoirs of excess tissue, available for local flaps.

The judgement involved in flap surgery is to assess how much tissue can safely be moved from one site to another whilst allowing closure of the donor site, preferably in a line of relaxed skin tension. Cosmetic or aesthetic units can be further divided into sub-units. Examples are the nose, eyelids, cheeks and temples (see Figure 2). From a surgical viewpoint, the importance lies in trying to reconstruct defects with tissue raised within the same unit and wherever possible avoiding moving tissue across a well-defined junction line from one unit to another.

The junction lines represent the areas between the cosmetic units and, along with visible wrinkle lines and those lines seen in facial expression, allow scar placement with maximum disguise. However, relaxed skin tension lines are not always visible and may not always coincide with somebody’s visible lines. These lines indicate the directional pull that exists in relaxed skin, and surgical incisions should be in parallel with these lines.

Tissue movement with local flaps

Classically there are three basic types of tissue movement in flap surgery:

- rotation

- advancement

- transposition

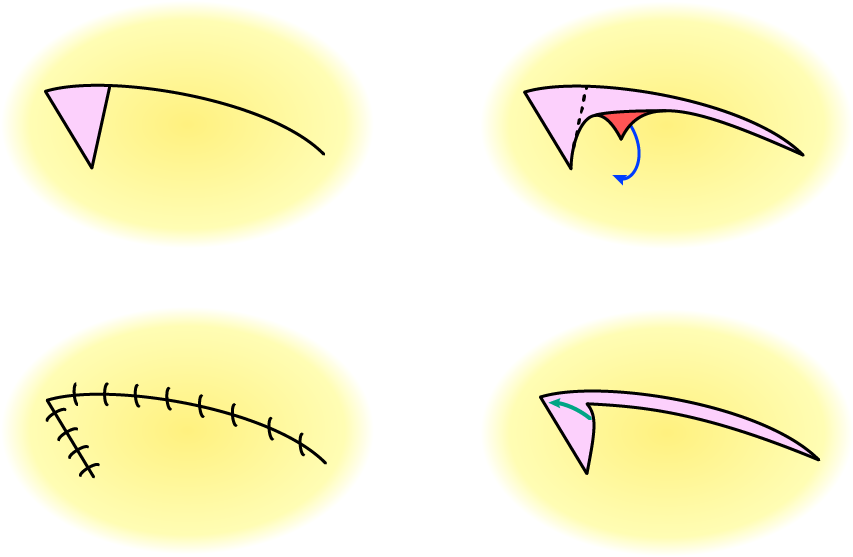

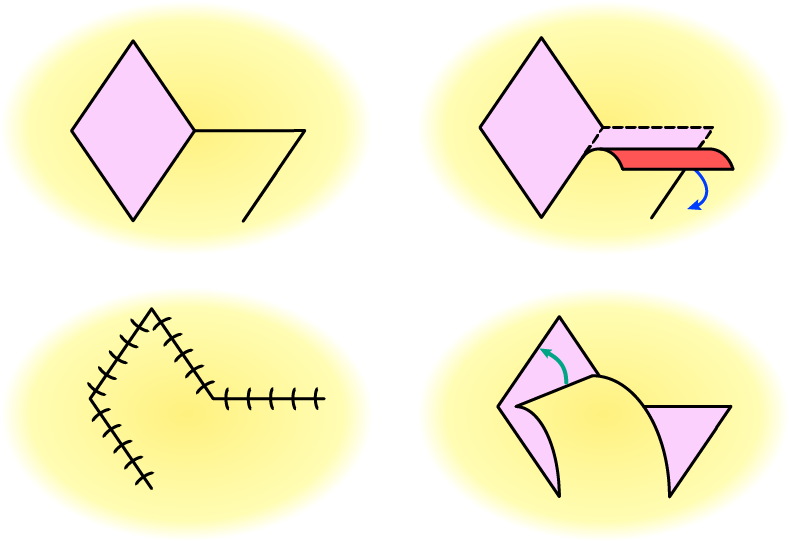

Figure 4 illustrates the principle of a simple rotation flap, suitable to cover a wedge-shape defect. The length of the incision line needs to considerably exceed the length of the short side of the defect (by about three to four times), the flap is rotated toward the far long side of the defect.

Figure 5 illustrates an advancement flap, together with a generally useful clever trick to ease movement of flaps and to ensure smooth wound closure – Burow’s triangle (named after its inventor Karl Heinrich Burow, a 19th century Prussian surgeon and ophthalmologist who had an interest in the treatment of open wounds), the additional excision of small triangles of tissue at suitable locations and angles to ease movement of the flap. An advancement flap involves movement of the flap in a straight line in order to cover the defect.

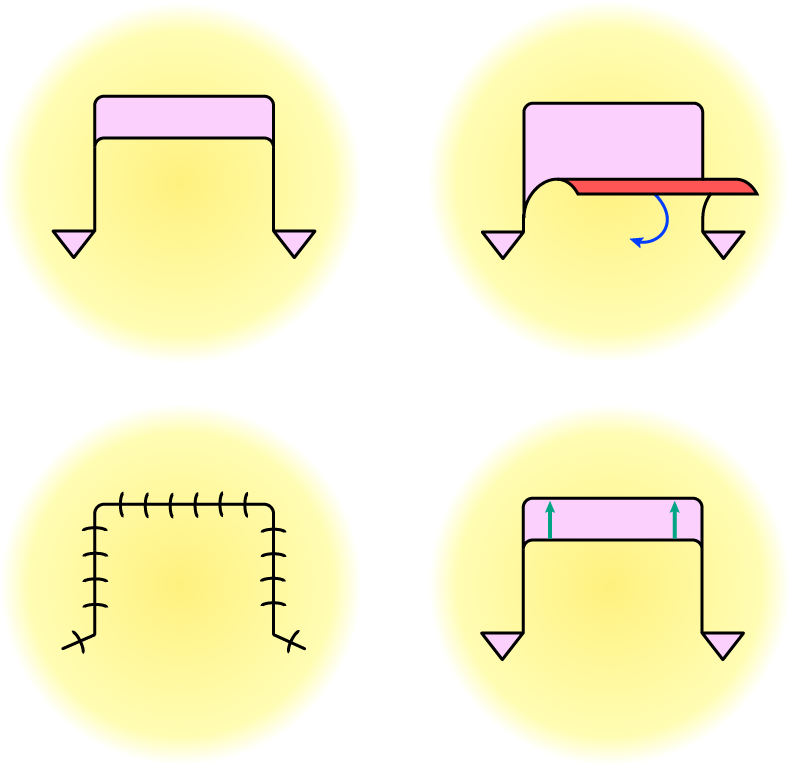

A rhomboid-shaped defect can be covered by a rhomboid flap (Figure 6). The geometry of a rhombus allows for a particularly versatile repair and coverage approach: the defect can be covered by a flap from the direction of any of the four sides of the rhombus. The flap movement involved is a transposition of the raised flap.

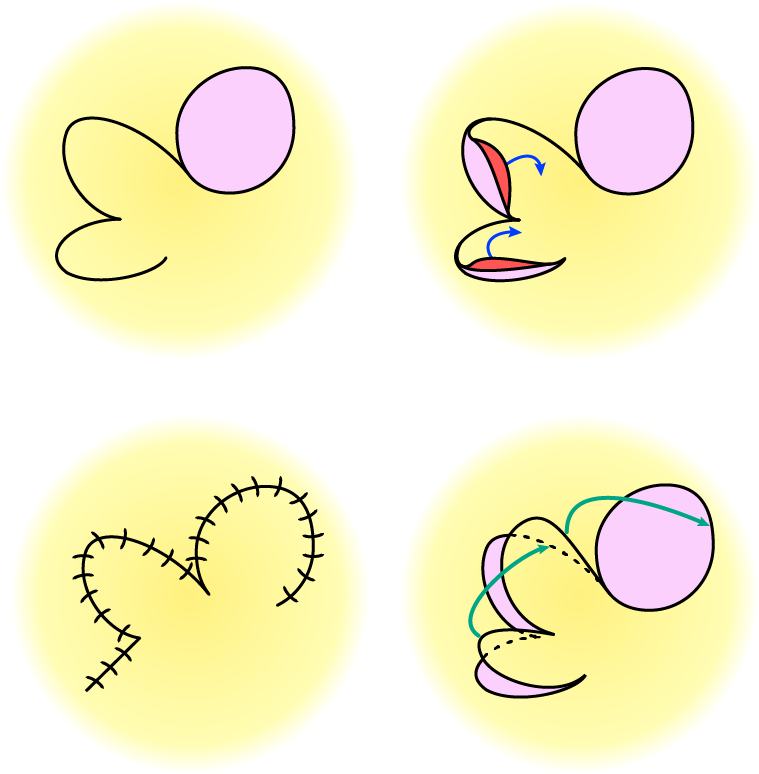

A bilobed flap is most suitable to cover circular defects (Figure 7). It consists of two (connected) sections, the larger of which is moved / rotated to cover the adjacent defect, the smaller section follows the movement and is used to cover the defect left behind by moving the first section to cover the defect. The defect left in the end by the second section is small enough and suitable for primary closure.

There are numerous, more elaborate local flap schemes, including combinations of flaps into sophisticated patterns that allow for equally sophisticated repair schemes.

Frequently flaps show combinations of different movements. When tissue is moved from one site to another, as well as the primary movement of the flap itself, there is a secondary movement of adjacent tissue to which it is sewn as the flap pulls that tissue toward it. The consequences of this pull and secondary movement are particularly important when flaps are close to free or distortable margins, such as eyelids (see Figure 8), lips or the nasal rim, so that this pull does not cause anatomical distortion.