Facial skin cancer

Contents

Having discussed general aspects of excision and repair of facial skin malignancies in the previous section, the following will provide some more specific comments about excision for basal cell carcinoma (BCC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and melanoma. Then we discuss repair strategies by local flaps in the different facial regions.

Surgical excision of BCC, SCC and malignant melanoma

BCCs are excised with a margin of 4 to 5 mm, although those with poorly defined margins are more difficult to judge and may need a wider margin. The use of Mohs’ micrographic surgery (after Frederic E. Mohs, 1938) can be useful in certain anatomical sites to determine clearance whilst minimising the extent of resection. Mohs’ surgery involves excision with chemical cauterisation and multiple repeat biopsies of the specimen until the margins are tumour free. Popular in the USA, the procedure is time consuming and costly, but it does offer advantages in the treatment of ill-defined morphoeic (infiltrative) BCCs and those encroaching free margins in the nasal and eye regions. Various modifications of this technique, using frozen sections or conventional histology, have been used to fit local resources. For example, in difficult cases a two-stage approach can be used leaving the wound dressed until histopathology is available. Final pathology results, looking carefully at the resection margins, can be reviewed prior to reconstruction as further marginal resections may be necessary.

In more straight forward cases, frozen section can be used to assess completion of resection. In these cases the resection and reconstruction can be performed as a one-stage procedure, following common clinical margin and reconstruction techniques.

Indications for Mohs’ surgery include:

- Tumour site (especially central face, around the eyes, nose, lips, ear)

- Tumour size (> 2 cm)

- Some histological subtypes (especially morphoeic, infiltrative, micronodular, basosquamous subtypes)

- Poor clinical definition of tumour margins

- Recurrent lesions

- Perineural or perivascular involvement.

For incompletely excised BCCs, there are various prospective and retrospective reviews that suggest that not all tumours will recur. Despite this, conventional wisdom decrees that tumours which have been incompletely excised, especially lesions incompletely excised at the deep margin, are all at high risk of recurrence.

SCCs and melanomas are excised more widely. The margin for excision for melanomas has decreased over the years as prospective trials have shown no disadvantage in the outcome with smaller margins. Current guidelines indicate margins of 1 to 3 cm, depending on the depth and size of the melanoma, and even below 1 cm in important anatomical regions such as the face.

Reconstruction of the scalp

The scalp is a relatively inelastic structure due to the presence of the galea aponeurotica (connective tissue that forms the middle layer of the scalp) and large flaps are required to reconstruct small defects. Should flaps be required to reconstruct large defects or maintain hairlines, then tissue expansion prior to flap surgery is an option (see Figure 1 for an example).

Alternatively very large flaps can be used bilaterally to allow sufficient laxity for closure (see Figure 2 for an example).

Many scalp lesions are treated with surgical excision below the galea layer. In this instance the pericranium (membrane that covers the skull) should be preserved to allow reconstruction with skin grafts. If this is not possible grafting onto bone can be successful if the dense cortical bone is removed and the graft placed in contact with diploe (spongy cancellous bone layer of the skull). Different types of skin grafts (full thickness of split thickness grafts) are available for large and small defects.

Reconstruction of the forehead

The forehead has characteristics of both the face and the scalp. In general, primary closure or local flaps are preferred in the management of defects here. As the skin is relatively tight, forehead laxity should be assessed prior to designing flaps as there is significant interpatient variation. Skin grafts on the upper forehead are acceptable, but flaps designed to match the horizontal lines of the forehead or the vertical lines that originate from the glabella region often give best results. Advancement flaps make maximum use of the horizontal creases and blend in, giving good aesthetic results (see Figure 3).

The anatomical position of the branches of the facial nerve can usually be predicted throughout the face, so that this structure can be spared whenever possible. It is acceptable to sacrifice the nerve if it is involved by the tumour (generally when it is not working). It is not acceptable for the facial nerve to be damaged in the flap surgery. Detailed knowledge of where the facial nerve branches lie in relation to musculature, the superficial musculoaponeurotic system layer and the other fascial structures of the face is vital. It is also good practice to lift facial flaps in the layers above those which contain sensory branches of the trigeminal nerve, so as not to create areas of anaesthesia beyond the surgical wounds.

If the facial nerve is damaged in the resection of the tumour, then the predicted deformity due to lack of muscle action can in part be corrected by careful design of the flap and/or suspension of the tissues with permanent, buried periosteal sutures (flap anchored to the membrane covering bone).

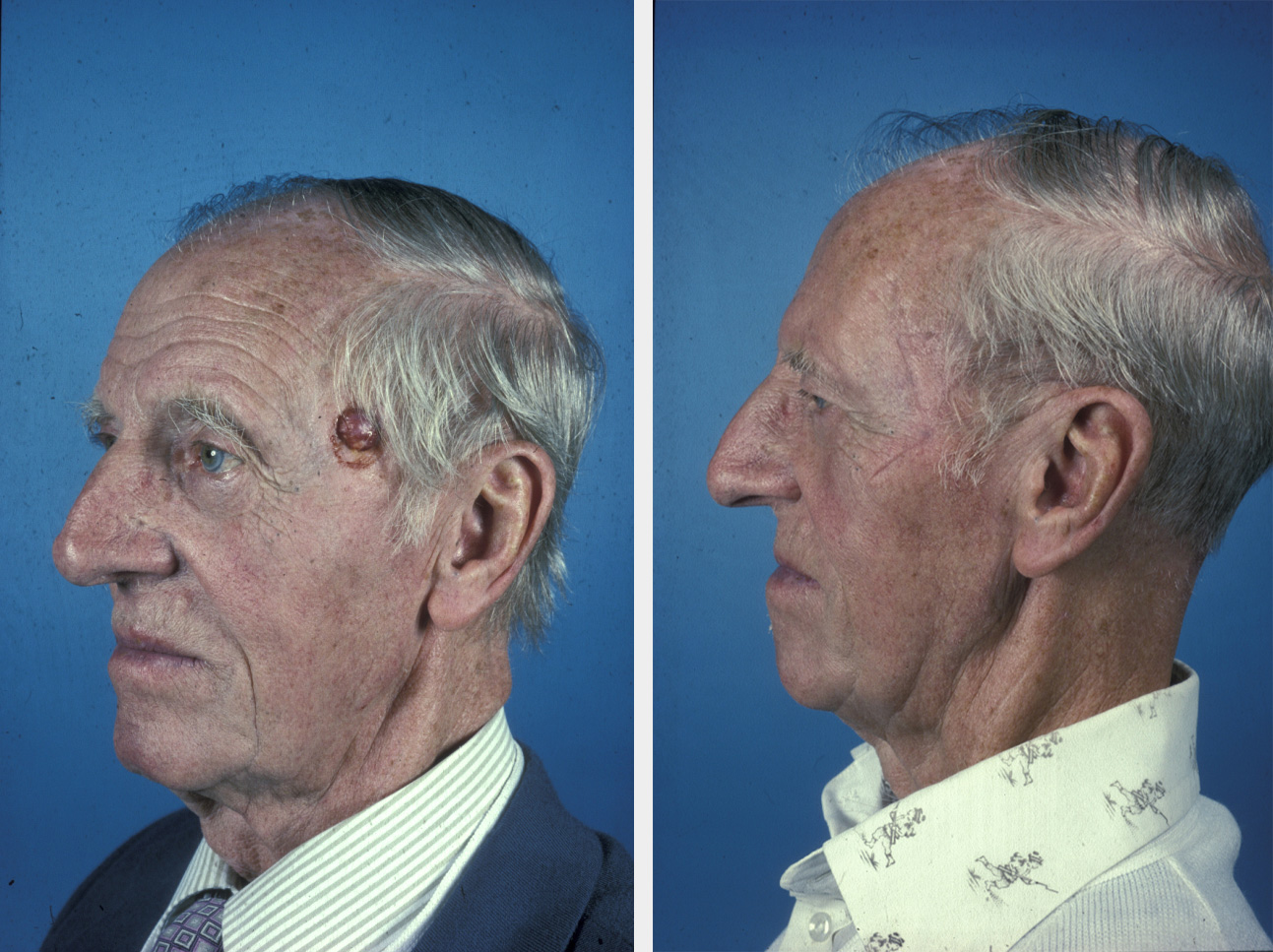

Reconstruction of the temple

The temple often has sufficient spare tissue for local flaps, such as the rhomboid flap (larger lesions may require skin grafting). Figure 4 shows an example before and after treatment.

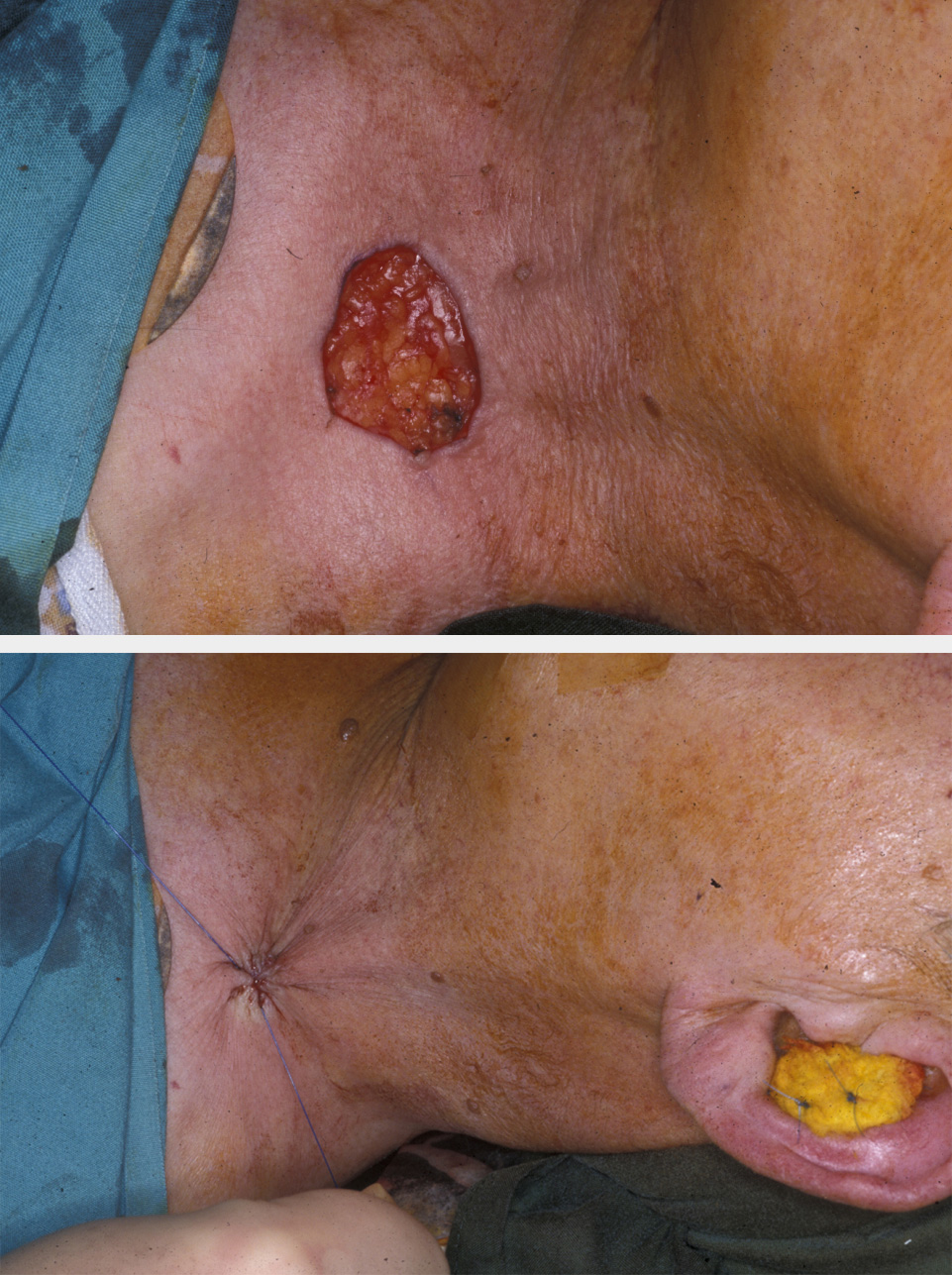

The use of the round block suture for larger lesions, particularly those that involve the hairline, can minimise the defect. This circumferential suture acts like a purse string in reducing the defect significantly when tightened (see Figure 5 for illustration).

Depending on tissue laxity this circumferential suture can either completely close the defect, or it can be used to reduce the defect by 50 to 60 %, so allowing a smaller skin graft to be used centrally. It has the advantage of pulling the hairline into a more anatomically correct position. The significant cutaneous deformities that result initially from this stitch gradually disappear as the skin relaxes. The stitch is usually retained for at least two weeks if a skin graft is used, or four weeks and more if complete closure is the desired result. This method of closure is a simple procedure that is particularly applicable in the temple, cheeks and neck with lax skin, typically in more elderly people.

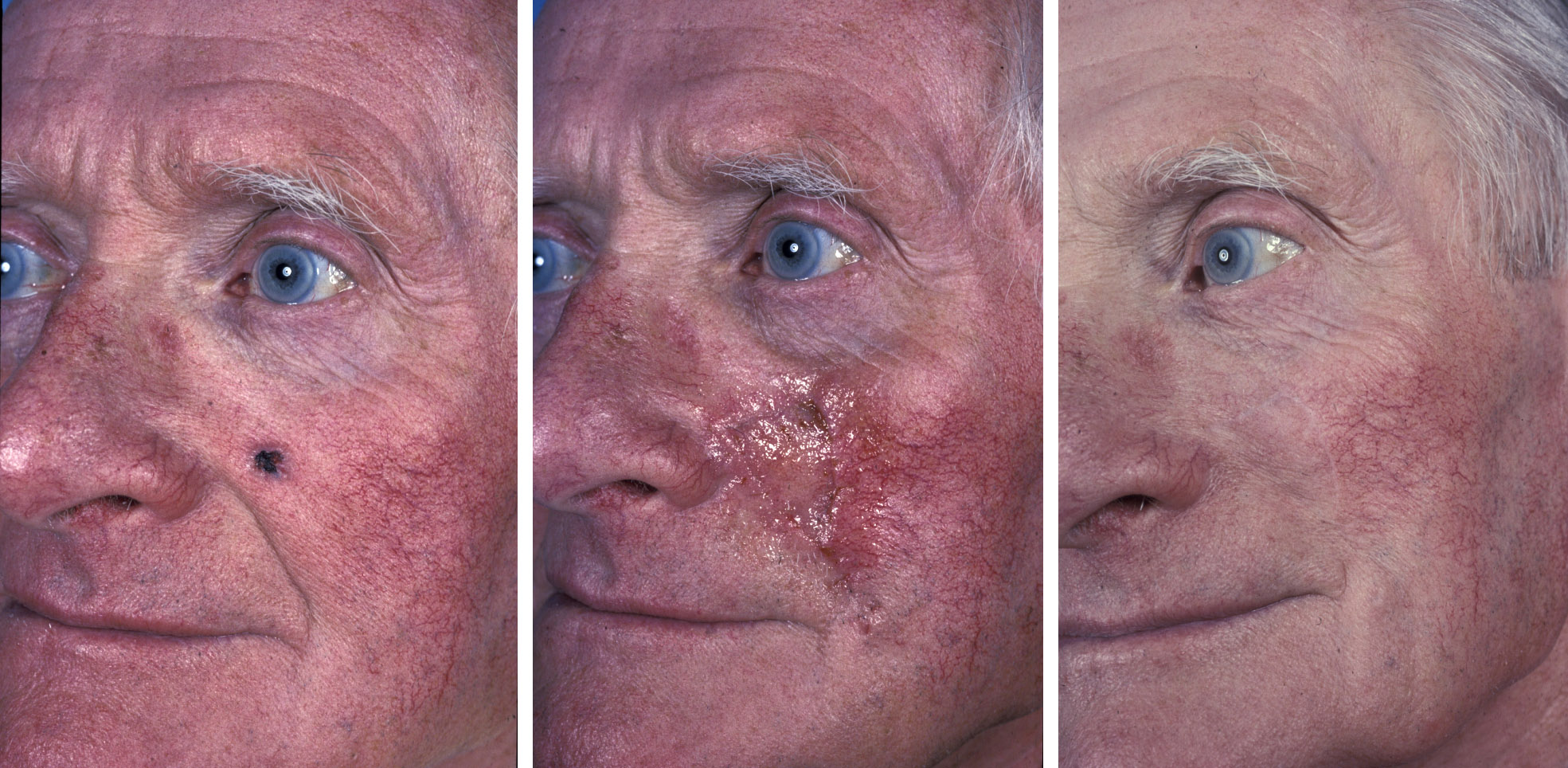

Reconstruction of the cheek

The cheek is a relatively safe area in which to practice cutaneous surgery as the skin is lax with favourable lines, particularly the junction lines, which hide scars well. These include the nasofacial, nasolabial and preauricular areas. The treatment of mid-cheek lesions has to take advantage of resting skin tension lines to minimise the aesthetic impact. This is particularly important in the younger cheek, which has fewer lines in which to hide the surgical incisions and resultant scars.

The cheek is frequently considered in three subunits: the preauricular cheek, the medial cheek, and the mid-cheek.

Reconstructive options vary according to these sites. In general the cheek has a significant amount of subcutaneous fat, which makes surgery relatively safe and the inherent elasticity of the cheek allows all forms of flaps to be undertaken, limited only by individual patient factors. The flaps are based on the vascular perfusion pressures of those vessels present within the flap base extending to its tip and not a simple length versus width formula (see Figure 6 for an example of a large rotation flap).

The medial cheek, as it meets the nose, is a common site for BCCs and the subcutaneously based triangular advancement flap is frequently useful (see Figure 7). This flap has the skin cut in a triangular fashion but with its deep connections via the subcutaneous fat being left intact. The laxity of the base allows advancement of the flap based on the subcutaneous pedicle and careful closure in a V-Y fashion.

Transposition flaps are frequently used on the cheek and careful assessment of where the scars will lie needs to be made to maximise the number of scars that will lie within the lines of relaxed skin tension.

Flaps in the region of the eyelid may need periosteal suspension sutures, which take up the tension within the flap to prevent excessive pull upon the lax tissue of the eyelid that can result in ectropion (drooping eyelid).

Reconstruction of the ear

The ear is morphologically complex, composed of skin and underlying cartilage, both of which are important for function and appearance. Significant tissue loss at the margins is particularly noticeable. Surprisingly, if the structure and shape of the ear can be maintained a reduction in size can often pass unnoticed.

Central defects of the ear should be repaired with full thickness skin grafting as a simple and effective reconstruction so long as the support for the margins is maintained.

Wedge excision of defects of the rim (helix) of the ear can be successful, but this should only be used for small defects which allow tension-free closure and no cupping or shape distortion of the ear due to tensions within the cartilage. Larger defects of the helix and other tissues of the ear are best addressed with rim or chondrocutaneous advancement flaps with an intact posterior skin pedicle providing the vascularity (see Figure 8). This allows reconstruction of the ear with a relatively normal shape, albeit somewhat smaller. One of the functions of the external ear is to act as a support for an individual’s glasses, it is easy to forget how important this can be.

Pedicle flaps from areas of lax tissue in the postauricular sulcus or the neck are possible and can reconstruct larger defects of the rim in two-stage techniques if rim advancements are not possible.

Reconstruction of the whole ear is a major undertaking and can either be addressed by a multistage surgical technique involving cartilage from another source, for example the rib, followed by soft tissue cover obtained from the temporoparietal region. This specialist service requires experience and is undertaken in only a few centres. Osseo-integrated implant-borne prosthetic reconstruction of the ear is frequently successful and is a cheaper and easier option.

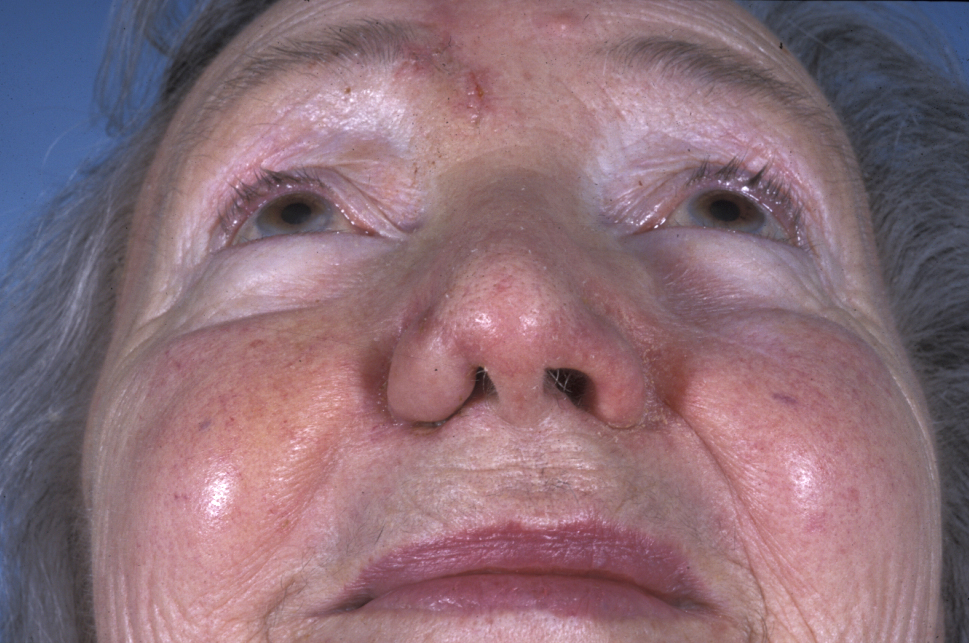

Reconstruction of the nose

This is one of the most challenging areas of the face to reconstruct and a variety of flaps may be used according to the site and extent of the tumour and which cosmetic subunits are involved in the tumour and the respective repair. Reconstruction should consider not only the skin of the nose, but the underlying structure including bone, cartilage and muscle, which are crucial for the maintenance of its respiratory function. Full thickness defects of the nose must involve internal and external reconstruction.

Mobile skin is at a premium on the nose with little being available towards the tip because of its fibrosebaceous nature and a relative absence of subcutaneous fat. The upper two thirds of the nose has slightly more mobile skin that may be used for primary closure or local flaps. Interpersonal variability in the amount of lax skin is common and every patient should be assessed by the simple method of pinching the skin to see what is potentially available. It is vital to maintain the free margins of the nose, particularly the alar rims, so that elevation or distortion does not occur. Despite the limited tissue available for local flaps, reconstruction of nasal defects is best undertaken with these procedures as this allows the return of normal contour, colour and texture. If a local flap is not feasible full thickness skin grafts are used.

Bilobed flaps (see Figure 9) and dorsal nasal rotation flaps are useful, but must be designed not to transgress the junction lines of the face or obtund the natural creases and hollows. The face, particularly around the nose and its junction with the cheeks, is a series of hills and valleys and flaps which cross the valleys, from one cosmetic unit to another, have the potential disadvantage of leaving a bridge across a sulcus which immediately catches the eye and appears abnormal in comparison to the unaffected side.

Large or structurally complex defects which cannot be reconstructed by grafts or local flaps call for a transfer of tissue from a nearby cosmetic unit utilising a two-stage technique where the tissue is transferred on a pedicle and allowed to regain a blood supply at the recipient site for several weeks before second stage division and insetting of the flap. The intervening pedicle is sacrificed and the site of donation of tissue is either closed primarily or with a skin graft.

This is illustrated very clearly by the paramedian forehead flap based on the supratrochlear artery, which is the flap of choice for reconstruction of large and complex nasal defects following cancer surgery (see Figure 10).

Cartilaginous grafts can be inset within the layers of the flap to give structural support to the nose. If a full thickness defect has been created, the inner aspect of the flap can be skin grafted or have a mucosal flap placed upon it from within the nose to complete the reconstruction. Division at 3 to 5 weeks occurs when the revascularisation has completed. The longer it is left, the safer sculpting of the flap will be. Alar rim reconstruction frequently (see Figure 11) requires a third stage for the in-turned flap which reconstructs the curved alar rim. This often needs delayed tertiary trimming, which cannot be undertaken at the second stage because of the risk to the vascularity of the flap.

Medial canthal or lateral nasal bridge defects can be reconstructed using transposition flaps from the glabella region, which are designed to adapt to the concave area of the lateral nose and the medial canthal region. The use of thermoplastic nasal splints to hold the flap into position until suture removal improves the appearance.

As with the ear, an implant-retained prosthesis following rhinectomy can have very satisfactory results and may obviate complex two-flap surgery.

Reconstruction of lip and chin

Treatment of cancers of the oral lip are discussed in the corresponding section about mouth cancer. Both lips are free margins; therefore avoidance of distortion presents the greatest challenge. Many landmarks exist on the lips which, if altered, may cause disfigurement. Wedge excision with primary closure will minimise deformity when possible. Similarly, facial grooves and folds (nasolabial, melolabial) can be blunted by otherwise effective and useful flaps (see Figure 12). This effect may be minimised by periosteal sutures to try to create a new groove.

Cutaneous defects are often treated with advancement flaps in the upper lip, such as bilateral advancement flaps or the subcutaneous triangular advancement flap (see Figure 13), which is particularly useful for lateral upper lip lesions close to the nasolabial or meliolabial fold. For centrally placed defects in the lip the best option is the perialar crescentic advancement flap, which can be used both unilaterally and bilaterally to reconstruct difficult larger defects.

The lower lip has the same problems and reconstructive considerations as the upper lip and any advancement flap should take note of the mentolabial crease in the design of advancement and rotation flaps.

The chin is a separate cosmetic unit. Flap design must take into account the inter-relationship between chin and lower lip, so that repair of one does not compromise the other (see Figure 14). Rotation flaps utilising the mentolabial crease or flaps utilising the crease at the cheek/chin junction offer the best results in this difficult and inelastic area. Design of these flaps must be considered carefully and often increased in size in order to diminish any vertical tension.