Fistula

We keep the oroantral communication / oroantral fistula as our worked example of treatment in a maxillofacial context. For this particular condition there is a timeline, with different treatment approaches.

Treatment of a primary oroantral communication

Treatment of a primary oroantral communication is to simply remove the tooth and any fragments of bone. Mobilising local gingivae and primary closure of the socket with a suture should allow a healthy clot to form within the area of communication. There is a high likelihood that this will heal. It is advisable to avoid nose blowing while the communication is healing. Temporary use of a nasal decongestant such as xylometazoline or oxymetazoline may be helpful, a course of broad-spectrum antibacterial medication, for example amoxycillin/clavulanic acid (effective against oral and nasal pathogens), may be required. The healing process needs to be reviewed to ensure that the communication has indeed healed and an oroantral fistula, with epithelial lining of the communication, has not formed.

Treatment of established oroantral fistula

Once a fistula is established treatment will require formal excision of the fistulous tract to gain healing both of the antral lining and of the oral lining. There are various surgical methods to achieve this.

The principles of treatment are:

- complete excision of the epithelial-lined tract;

- removal of any foreign bodies;

- mobilisation of tissue on the oral side and closure using an incision line that is capable of healing by primary intention.

This means that the incision line must rest on healthy bone or on another layer of vascularised tissue. There are three basic ways to achieve this:

- the buccal advancement flap;

- the buccal fat pad flap;

- the palatal finger flap.

Buccal advancement flap

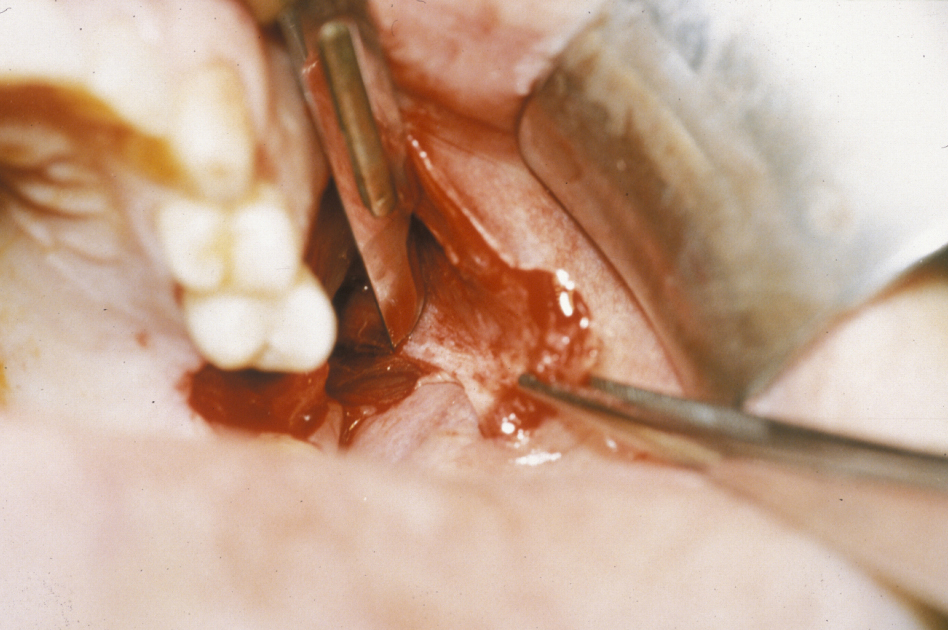

This procedure uses a three-sided advancement flap of buccal mucosa. The flap is mobilised by making an incision through the periosteum to allow the flap to be stretched without tension over the defect (Figure 1).

It is essential that the suture line rests on sound bone; otherwise this flap will inevitably dehisce (split). The disadvantages of the buccal advancement flap are a relatively shallow sulcus (groove between the jaw and the cheek) postoperatively and the risk of flap dehiscence because it is a single-layer closure and must be closed over bone (Figure 2).

Buccal fat pad flap

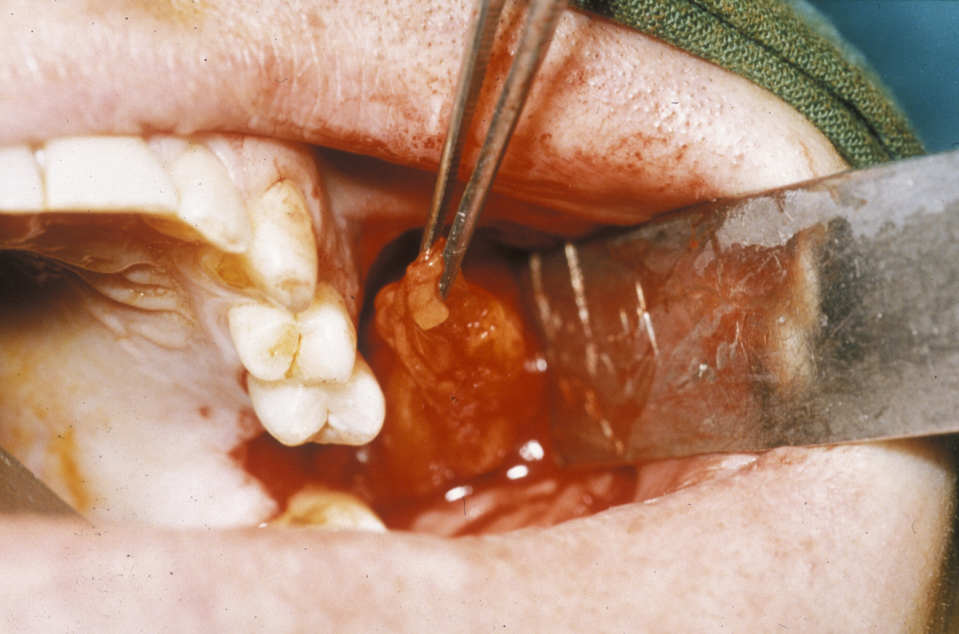

This procedure is approached using a similar incision to the buccal advancement flap (see above), but when the periosteum is incised, an artery clip is passed into the submucosa to identify the buccal fat pad (Figure 3).

This is an axial flap that lends itself beautifully to the closure of oroantral fistulae. It can be used as an isolated flap where the vascularised fat fills the defect and is held in place with vertical mattress sutures (common, interrupted suture technique designed for minimal tension and scarring), thus allowing the raised buccal flap to be repositioned in the buccal sulcus to maintain depth (Figure 4).

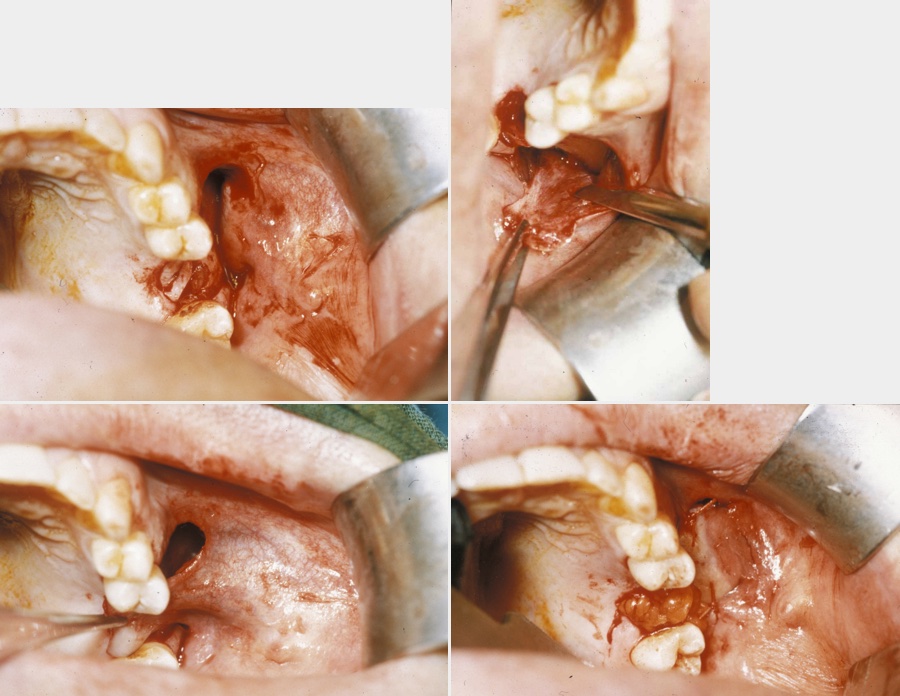

A combination of buccal fat pad and buccal advancement flap is probably the most effective way to close an oroantral fistula. The advantage of the technique is that the vascularised buccal fat pad fills the defect below the buccal advancement flap. This provides mucosal closure and thereby creates a double-layered vascularised closure that virtually has no chance of dehiscence and breakdown. The technique is illustrated in Figure 5.

Palatal finger flap

This is the third technique for closing chronic or persisting oroantral fistulae where buccal advancement flaps or fat pad flaps are not appropriate. The palatal finger flap is based on the greater palatine artery. The palatal flap is a very stiff and immobile flap, although it provides extremely robust, well-vascularised tissue. It is possible to isolate the palatal flap completely on the greater palatine vessels, which makes it much easier to suture into position but is more demanding surgically. The disadvantages of the palatal flap are that it leaves a raw defect on the palate that requires some kind of palate coverage because it is extremely painful for weeks afterward and it is difficult to rotate the flap into position. This flap is one of those procedures that look very straightforward when it is drawn on a diagram but in reality, because of the stiffness of the palate, is actually extremely awkward to achieve. For the palatal finger flap (indeed all these flaps) postoperatively nose blowing needs to be avoided. A nasal decongestant is useful, as well as a course of antibacterial medication.

Read about timelines of treatment and outcomes for fistula.