Jaw joint problems

Here we contrast the normal joint function with general signs and symptoms of abnormal temporomandibular joint (TMJ) function.

The TMJ is a synovial joint (a capsule connecting bones and filled with synovial fluid (lubricant for the joint)) in which the mandibular condyle (head of the mandible) articulates with the base of the skull at the glenoid fossa and articular eminence. Interposed between the two is the articular disc (or meniscus), the function of which is to contribute to the smooth action of the joint. The disc is also believed to be involved in many of the disorders commonly seen. The disk is divided into three zones: a thick posterior band, a thin intermediate zone and a slightly thicker but narrow anterior band.

The TMJ nerve supply arises from the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve. The auriculotemporal nerve innervates most of the TMJ mainly anterolaterally (front/side) and small branches of the masseteric and deep temporal nerves supply the posterior (back) aspect. The TMJ vascular supply arises from the external carotid artery via the internal maxillary artery and the superficial temporal artery.

Normal function of the jaw joint

Normal movement in the temporomandibular joint should be smooth and pain free. Both jaw joints are almost (bone does have some plasticity) rigidly linked together by the horseshoe-shaped mandible and therefore move together - it is not possible for one joint to move without affecting the other. Consequently, any disorder of movement involving one joint will by necessity effect the opposite one.

Initial mouth opening (up to 1 cm) involves a hinge-type movement, analogous to that seen in the knee or phalanges (the bones making up hands and toes). However, the remainder (and the majority) of mouth opening involves a bodily shift, or translation, of the condyle (head of the mandible) as it moves down the articular eminence (the opposite part of the joint, involving the temporal bone, underneath the temple). Closure is essentially the reverse of this. Side to side movements of the mandible involves a mixture of rotation of each condyle through a vertical axis and a minor degree of lateral shift.

In the normal temporomandibular joint the meniscus (the disc that enables smooth movements of the joint) is placed on top of the condyle and the two move in harmony as the mandible moves. Movement of the disc is possible due to its elastic attachments and the attachment of the lateral pterygoid - an important muscle in mouth opening.

Symptoms and signs of abnormal jaw joint function

Pain - this is probably the most common symptom. Pain may arise from the joint capsule, from ‘retrodiscal’ tissues or associated muscles such as the lateral pterygoid or masseter. Often the pain can be well localised to the joint, making diagnosis relatively straight forward. However, referred pain or pain arising within the muscles can be experienced elsewhere. Pain aggravated by chewing or stressing the joint points heavily to a musculoskeletal cause.

Joint noises – these are usually experienced as clicking and grating. They can occur in otherwise asymptomatic jaw joints. Grating noises may be experienced s a result of some destructive processes resulting in loss of the smooth articular surfaces and irregular joint movement. In mild cases no cause can be found, although arthroscopically (internal optical inspection) there may be evidence of mild degenerative changes with debris in the synovial fluid. The noises can be heard without the use of stethoscope amplification.

Limitation of mouth opening, trismus - it is important to draw a distinction between limitation of movement resulting from obstruction within the joint and that caused by muscle spasm.

Deviation on mouth opening – normal mouth opening should be symmetrical and pain free, interincisal opening should approach 40 mm although this varies with height, occlusion and dentition (see Figure 2).

Deviation may result from mechanical interference or pain. When deviation is prolonged, this new movement becomes subconscious and automatic and may continue after the initial cause has resolved (see Figure 3).

Clicking – distortion of the meniscus in the jaw joint prevents smooth movement of the condyle. The condyle may have to ‘jump’ over the periphery of the meniscus to continue moving. This is felt as a click.

Locking – untreated, clicking may progress to locking: the meniscus becomes so abnormally shaped and displaces that is effectively acts like a door stop. This results in ‘locking’ of the jaw.

Imaging studies of the temporomandibular joint

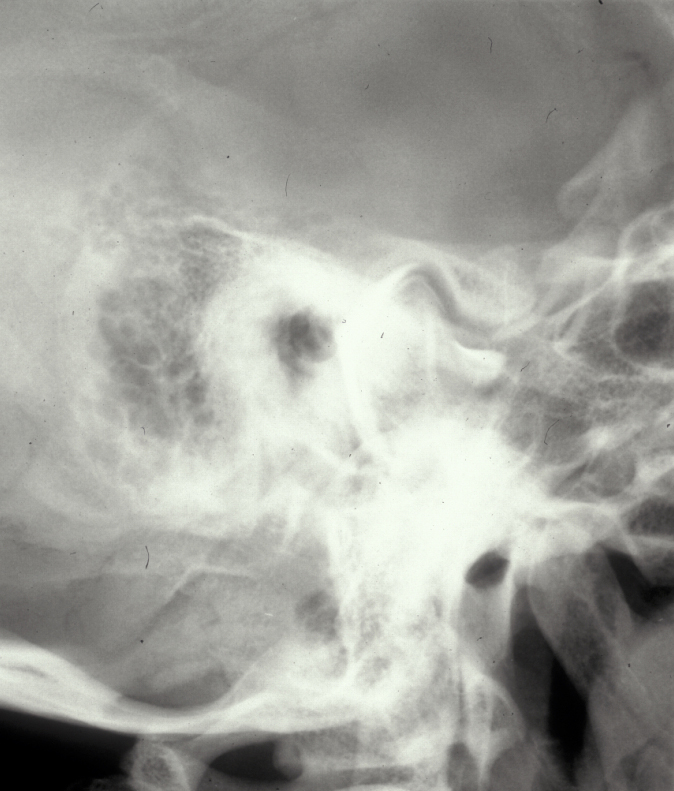

Plain X-ray radiographs are relatively easy to obtain in the clinic but they really play a minor role in detecting pathology of the jaw joint (see Figure 4 for examples).

The temporomandibular joint is a complex three-dimensional structure and conventional radiographs only show a two-dimensional projection view, taken through one part of the joint. Only gross pathology can be picked up in this way (see Figure 5 for an example).

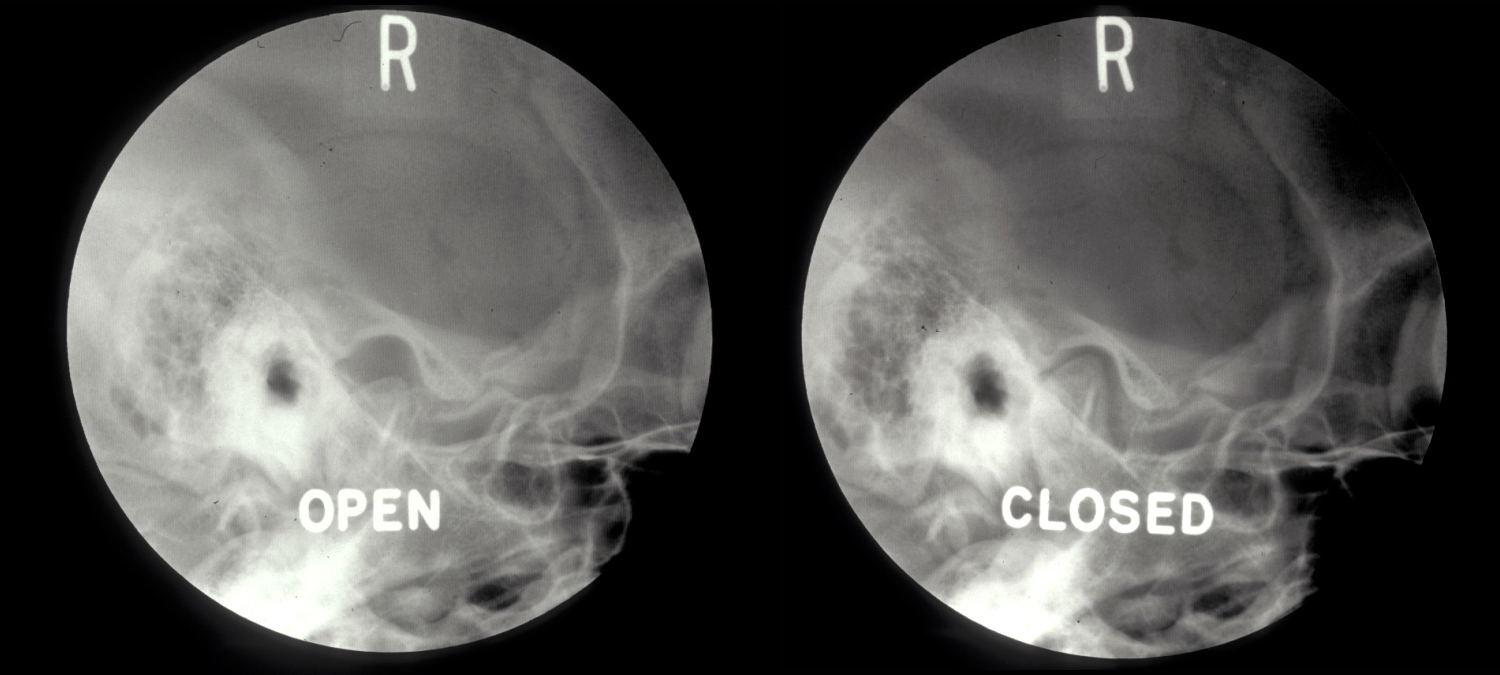

TMJ arthrography involves the direct injection of a contrast medium into one or both of the joint spaces and provides information on joint function, particularly that of the meniscus. TMJ arthrography is a technically demanding investigation (see Figure 6).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is increasingly used in the study of the temporomandibular joint because it is particularly useful for visualising the associated soft tissues (for example disc, lateral pterygoid muscle etc.). MRI is also useful in studying the vascularity of the condyle. Currently MRI is the imaging modality of choice, although recent reports suggest an increasing role for ultrasound scans in imaging of the temporomandibular joint.