Cyst

Here we describe both epithelial and nonepithelial cysts affecting different areas of the head and neck region. Cysts affecting the jaws are common.

Epithelial cysts

Epithelial cysts of the jaws can be subdivided according to the origin of their epithelial lining. This epithelium can either originate from the tooth-forming organ (odontogenic) or from other sources such as areas of inclusion of epithelium when the embryonic processes of the face fuse (non-odontogenic). Odontogenic cysts account for the large majority (90%) of jaw cysts.

A good medical history can yield a great deal of information about the likely nature of the problem. Signs and symptoms of the various types of jaw cysts are frequently similar. They usually present either as an incidental radiographic finding or as a chronic, painless swelling. Pain becomes a feature when the cyst becomes infected or is so extensive as to cause a pathological fracture, most commonly of the mandible.

Common physical signs of jaw cysts include:

- Swelling (intra- or extra-oral)

- Displaced teeth

- Mobile teeth

- Crepitus (peculiar ‘egg-shell’ crackling or grating feeling or sound under the skin)

- Fluctuation

Other signs may be more specific to particular cysts.

Many cysts affect other sections of the mouth or the neck.

Odontogenic cysts (jaws)

There are several different types of odontogenic cysts of the jaws:

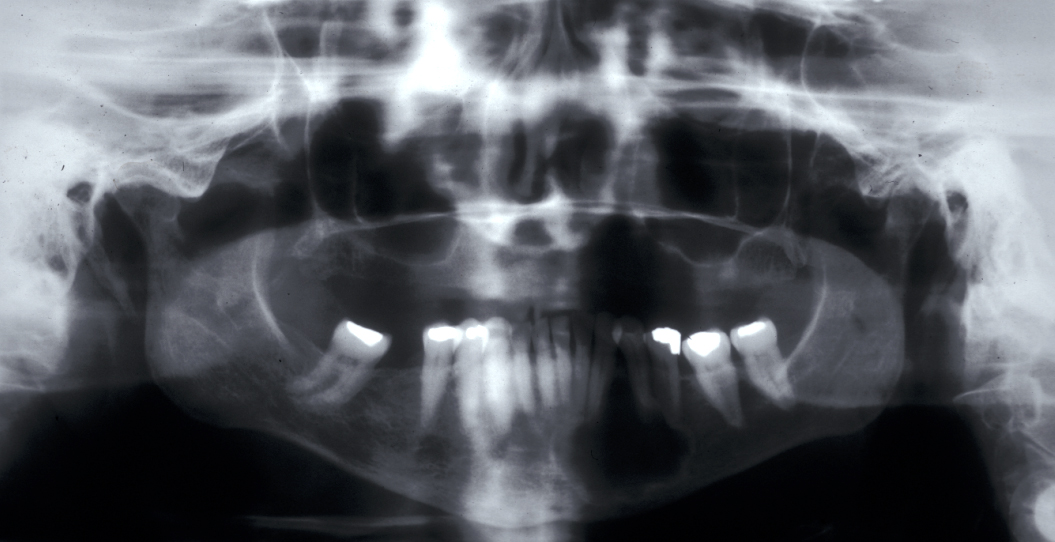

Radicular cyst – in a non-vital tooth, this cyst appears as a rounded periapical radiolucency in an X-ray radiograph, with loss of lamina dura (bone surrounding the tooth socket) and a sclerotic margin if it is a long-standing lesion. Figure 1 shows an example.

Residual cyst - a radicular cyst is left behind after tooth removal and continues to grow.

Dentigerous cyst – usually found as an incidental finding on radiographs. The cyst envelopes the crown of a tooth. Lower third molars (wisdom teeth) are most frequently affected, followed by upper canines and lower premolars.

Eruption cysts - these cysts are soft tissue analogues of dentigerous cysts and usually overlie unerupted teeth. They tend to affect children and involve deciduous teeth (milk teeth). They appear as a soft, translucent, bluish swelling (see Figure 3).

Keratocyst / keratoystic odontogenic tumour (KOT) – this cyst is thought to replace a missing tooth (may be a supernumerary). It is associated with unerupted teeth in 40% of cases. It appears radiographically as a uni- or multiloculated radiolucency with a well-defined sclerotic margin. These cysts tend to grow in an antero-posterior direction and therefore do not always cause bony expansion.

The lesion formerly known as the odontogenic keratocyst was redesignated by the World Health Organisation as the keroatocystic odontogenic tumour (KOT) in 2005. This change was based on the aggressive nature, histology, and genetics of the lesion. While this seems to be of interest to pathologists it makes little difference to the clinical management and certainly does not justify treating these cysts as ‘malignancy’. My personal bias against this change in terminology was confirmed by the WHO changing the name back to odontogenic keratocyst in 2017. It’s tempting to suggest some people have too much time on their hands.

However, multiple keratocysts are a feature of ‘naevoid basal cell carcinoma’ syndrome (Gorlin syndrome – multiple basal cell carcinomas, calcified falx cerebri, rib anomalies). This syndrome is characterized by new cysts appearing throughout the jaws over the lifetime of the patient (as opposed to locally recurring after treatment). The cysts do not need to be managed particularly radically; indeed as the cysts often start at a young age overaggressive surgical treatment can be a great disservice to the patient.

Non-odontogenic cysts (jaws)

Include nasopalatine (median palate, often between the roots of the central incisors - incisive canal), globulomaxillary (between maxillary lateral incisor and canine), median (middle of the hard palate) and nasolablial (soft tissue of upper lip) locations.

Nasopalatine cysts - palatal swelling with pain and salty discharge is commonly associated with tooth displacement and loss of vitality. Can be suspected radiographically when the incisive canal is greater than 6 mm in diameter.

Nasolabial cysts - soft tissue swelling which obliterates the nasolabial fold.

Dermoid cysts

These are developmental cysts and arise at various lines of fusion where exodermal tissue can become submerged in the development and fusion of the facial processes. These later secrete sebaceous material and appear as cystic swellings which are called dermoids.

Oral dermoid cysts - this developmental cyst is found in the midline of the neck, above the mylohyoid muscle where it causes swelling in the floor of the mouth. If it appears as an intraoral swelling, it can be confused with a ranula (see below). Oral dermoid cysts tend to present in young adults. There is a male to female ratio of 1:1.

There are three general variants:

- The common epidermoid cyst which tends to contain a keratinous material (material that normally makes up the surface of skin) similar to keratocysts (see above).

- The true dermoid cyst which is lined by squamous epithelium and contains skin appendages.

- The very rare keratoid cyst which may contain other external derivatives.

Angular dermoid cysts – this is an epidermal cyst arising above the lateral canthus of the eye at the zygomaticofrontal suture. It presents in childhood and may have an intracranial extension. Of all craniofacial dermoid cysts, the commonest site of origin is between the outer angle of the eye and the hairline.

Dermoid cysts can also occur on the nasal bridge, submentally (upper front of neck) without presenting in the mouth and very low in the neck, just below the sternoclavicular notch (near the collar bone).

There is seldom any need for a specific investigation with dermoid cysts. However, if there is any suspicion, particularly of an angular dermoid cyst of the lateral border of the eye being fixed to the underlying tissues, it should be investigated by CT scan as on rare occasions dumb bell phenomena can occur where two dermoids, one intracranial and one extracranial are connected.

Mucocele

Mucoceles are mucous extravasation (leakage) cysts where saliva leaks from a traumatised minor salivary duct and pools of usually mucinous saliva create a connective tissue capsule. They almost always affect the lower lip (see Figure 6).

Ranula

Ranulas are mucoceles of the floor of the mouth, usually arising from the sublingual salivary gland or the duct of the sublingual salivary glands. Plunging ranula cross the mylohyoid muscle (below the floor of the mouth) and can appear in the neck.

Branchial cysts (neck)

There are two theories of origin of these developmental cysts:

- The branchial cyst is a remnant of the second branchial arch which is a specific cluster of cells present in the foetus which go on to become other anatomical structures but this fails to explain why most branchial cysts present in adolescence or adulthood.

- The branchial cyst is actually an epithelial inclusion within cervical lymph nodes. This is supported by the fact that branchial cysts have no internal opening and most branchial cysts do include lymphoid tissue in their wall.

Other theories exist based around the embryonic development theory. There is no agreement as to which theory is the more favourable although in terms of popularity origin from the branchial apparatus is probably the leader.

Two thirds of these cysts lie anterior to the anterior border of the upper third of the sternomastoid muscle (large muscle either side of the neck near the surface), one third will lie lower than this. Branchial cysts usually present as a persistent swelling although pain can be a feature if the cyst is infected. These cysts are more frequent in males than females, and on the left than on the right side, approximately 2% are said to be bilateral.

Branchial cysts should be diagnosed clinically. Specific imaging, either by ultrasound or CT scans can confirm an isolated cyst in a classical position. Biopsy by fine needle aspiration cytology may demonstrate cholesterol crystals but is otherwise unhelpful.

Thyroglossal duct cysts (neck)

The thyroid gland develops from the tuberculum impar at the junction of the posterior and anterior two thirds of the tongue, which descends during foetal life to the neck. In some instances no migration occurs and the thyroid gland can develop as a lingual thyroid. On rare occasions this may be the only functioning thyroid, but more commonly the tract of descent is the source of pathology, usually in the form of a thyroglossal duct cyst (the persisting thyroglossal duct runs from behind the thyroid gland, through, around or in front of the hyoid bone and ends at the foramen caecum in the tongue). Thyroglossal fistulae may occur when an infected thyroglossal cyst discharges spontaneously onto the skin, or when inadequate surgery has been attempted to excise a thyroglossal cyst.

Thyroglossal duct cysts most frequently present in young children, although the age range is wide. The majority of these cysts lie in the midline of the neck (90%). These are mostly painless central neck masses which move on swallowing and elevate on protruding the tongue (see Figure 7).

These cysts are usually easy to diagnose on a clinical basis. If there is normal function of the thyroid gland (euthyroid with a normal thyroid stimulating hormone test), no further investigations are needed. An ultrasound scan of the neck may be recommended to image the usual position of the thyroid.

Cystic hygroma / lymphangioma (neck)

Cystic hygroma is the most common form of lymphangioma (a malformation of the lymphatic system) and is more common in the neck than in the mouth. It presents as a cystic mass which infiltrates through tissue plains and will not spontaneously resolve. They are divided into macrocystic (usually easily removed) and microcystic. There may be problems associated with completely resecting the non-malignant mass microcystic version.

Nonepithelial cysts

These pseudo-cysts (because these cavities do not have an epithelial lining) are fluid-filled cavities within the bone. They can be broadly divided into three types:

- Aneurysmal bone cyst

- Solitary bone cyst

- Stafne’s idiopathic bone cyst / cavity

Aneurysmal bone cyst (jaws)

These are benign bone lesions characterised by blood-filled spaces and are most commonly found in the long bones (98.5%). They are rare in the facial bones and when they do occur they are usually seen in the mandible.

The aetiology is unknown. The lesions can be divided into two categories. Primary (70%) aneurysmal bone cysts have no associated previous lesions and can be congenital (no history of trauma) or traumatic. Secondary (30%) aneurysmal bone cysts have a history of previous lesions such as fibrous dysplasia or a dentigerous cyst (see above).

Clinically, aneurysmal bone cysts present as a firm painless swelling, which expands slowly. Sudden expansion and pain is usually indicative of sudden bleeding inside the cyst, often following minor trauma. Although the teeth generally remain vital, there may be malocclusions (misalignment of teeth) or root resorption.

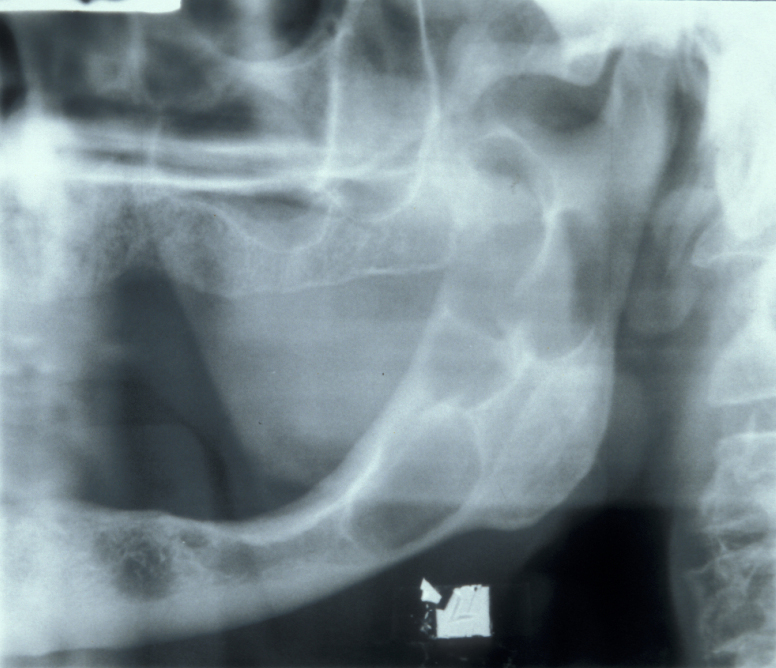

Radiographically, aneurysmal bone cysts form unilocular (consisting of a single chamber) or multilocular (consisting of multiple chambers) radiolucencies, which can be mistaken for ameloblastoma or keratocysts (see above).

Histologically, multiple blood filled spaces are seen which are separated by fibrous septa (walls) with scattered multinucleate giant cells.

Solitary bone cyst (jaws)

These are often seen in the humerus (upper arm) and femur (upper leg). They rarely occur in the head and neck region, and when they do they are almost always in the mandible.

The aetiology is unknown but it is thought to be due to a haemodynamic (related to blood flow) imbalance within the bone. It has been suggested that solitary bone cysts may be associated with a history of trauma. However, the link is not strong and the history of trauma may range from months to years prior to occurrence of the cyst.

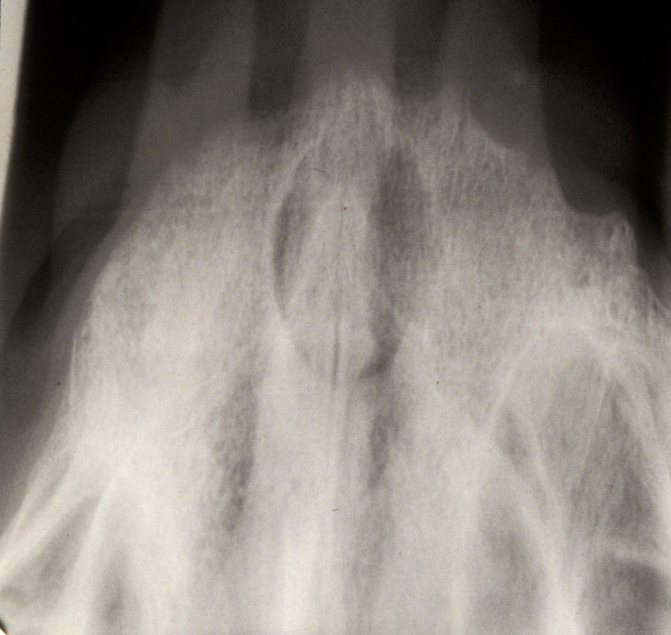

Clinically, solitary bone cysts are usually asymptomatic but there is occasionally bone expansion and radiographically there is an irregular radiolucency with well-defined scalloping between the roots of the teeth. Histological examination shows a thin layer of loose vascular fibrous tissue but no epithelial lining and there is no cyst fluid.

Stafne’s idiopathic bone cavity (jaws)

This is thought to be a developmental defect on the lingual aspect (facing the tongue) of the mandible that contains a portion of normal submandibular salivary gland (or sublingual salivary gland when seen in the anterior (front) mandible).

Clinically, these cavities are asymptomatic and are usually discovered as incidental findings on radiographs, where they appear as a well-circumscribed area in the body of the mandible with a sclerotic margin. Their location and lack of symptoms is often diagnostic. However, further investigation (such as sialography (X-ray investigation of the salivary glands, using contrast agent), CT or MRI scans can confirm the diagnosis.