Prasugrel

Prasugrel is one of several widely prescribed antiplatelet medications, used to prevent thrombosis (blood clots) in arteries and arterioles. A common reason for long-term treatment with prasugrel, often in combination with low-dose aspirin, is risk reduction for stroke and cardiovascular diseases.

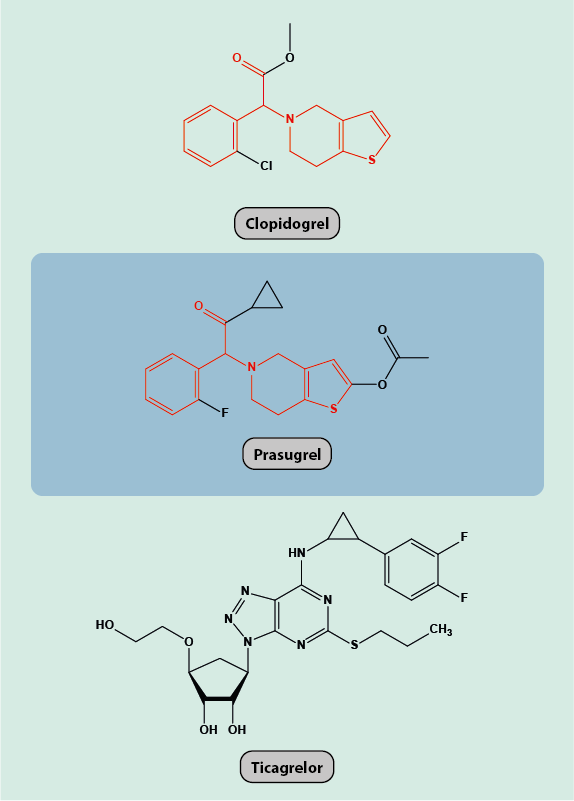

Prasugrel as depicted in Figure 1 is a pro-drug that first needs to be converted to its active form once administered. Other than for clopidogrel, for prasugrel this chemical conversion to an active metabolite only requires hydrolysis and does not depend on the action of liver enzymes. Accordingly, prasugrel may be a more suitable choice of antiplatelet medication for people with reduced liver function. Also, antacid medications (proton pump inhibitors, which suppress the production of stomach acid) do not reduce the antiplatelet activity of prasugrel (but antacid medications inhibit the activity of clopidogrel).

Once prasugrel is converted to its active metabolite, the active metabolite irreversibly blocks a receptor (a protein, P2Y12) that is found on the surface of platelets. P2Y12 is an important regulator protein in the cascade of reactions leading to blood clotting. Blocking P2Y12 prevents the aggregation of platelets and thus the formation of a blood clot. The resulting, most prominent adverse effect of prasugrel (and other antiplatelet medications) is a tendency for excessive bleeding. The overall effects of clopidogrel and ticagrelor are similar to those of prasugrel, as all three drugs block the P2Y12 receptors on the platelet surface. However, in most people prasugrel hinders platelet aggregation more rapidly and more profoundly than clopidogrel.

A tendency for excessive bleeding is obviously relevant for any oral and maxillofacial surgical interventions. As the effect of a dose of prasugrel persists for several days, wherever possible careful consideration needs to be given to modification of antiplatelet medication ahead of surgical interventions. This is possible for many elective procedures but obviously is not an option for trauma and other emergency situations leading to blood loss. In considering whether or not to modify antithrombotic or anticoagulant medication, an individual risk benefit analysis is needed. For most minor surgery local measures can control unwanted bleeding if the risk of modifying medication is high. The lack of effective reversal of these agents can also be problematic.