Mouth cancer

Contents

Here we concentrate on surgical treatments for oral cancer. More extensive surgery will usually require reconstruction of the resulting defects. Reconstructive surgery in the head and neck region is a big topic of its own, not just in the context of surgical treatments of mouth cancer. Accordingly, there is a separate section dealing with reconstructive surgery.

Some general aspects of surgical treatment of mouth cancer

Surgery can be confined to tumour ablation alone, with or without reconstruction. Where there is regional lymph node involvement, neck dissection (see below) is carried out at the same time. In many instances, reconstruction is simultaneous. If so, the surgery will be more extensive, in the form of a series of procedures (such as tracheostomy, neck dissection, access surgery, dental clearance, tumour ablation followed by immediate reconstruction and closure of the donor site). In such instances, a two team approach is preferred because the workload is shared, and the total anaesthetic time is reduced, with the flap being harvested at the same time as ablative surgery is performed.

Airway

There are several issues to consider as part of tumour resection. The airway must be secured during and after the surgery. If there is a significant risk to the airway, such as likely oral or neck swelling, a temporary tracheostomy should be performed. Figure 1 displays the equipment needed for a tracheostomy.

Access for tumour resection

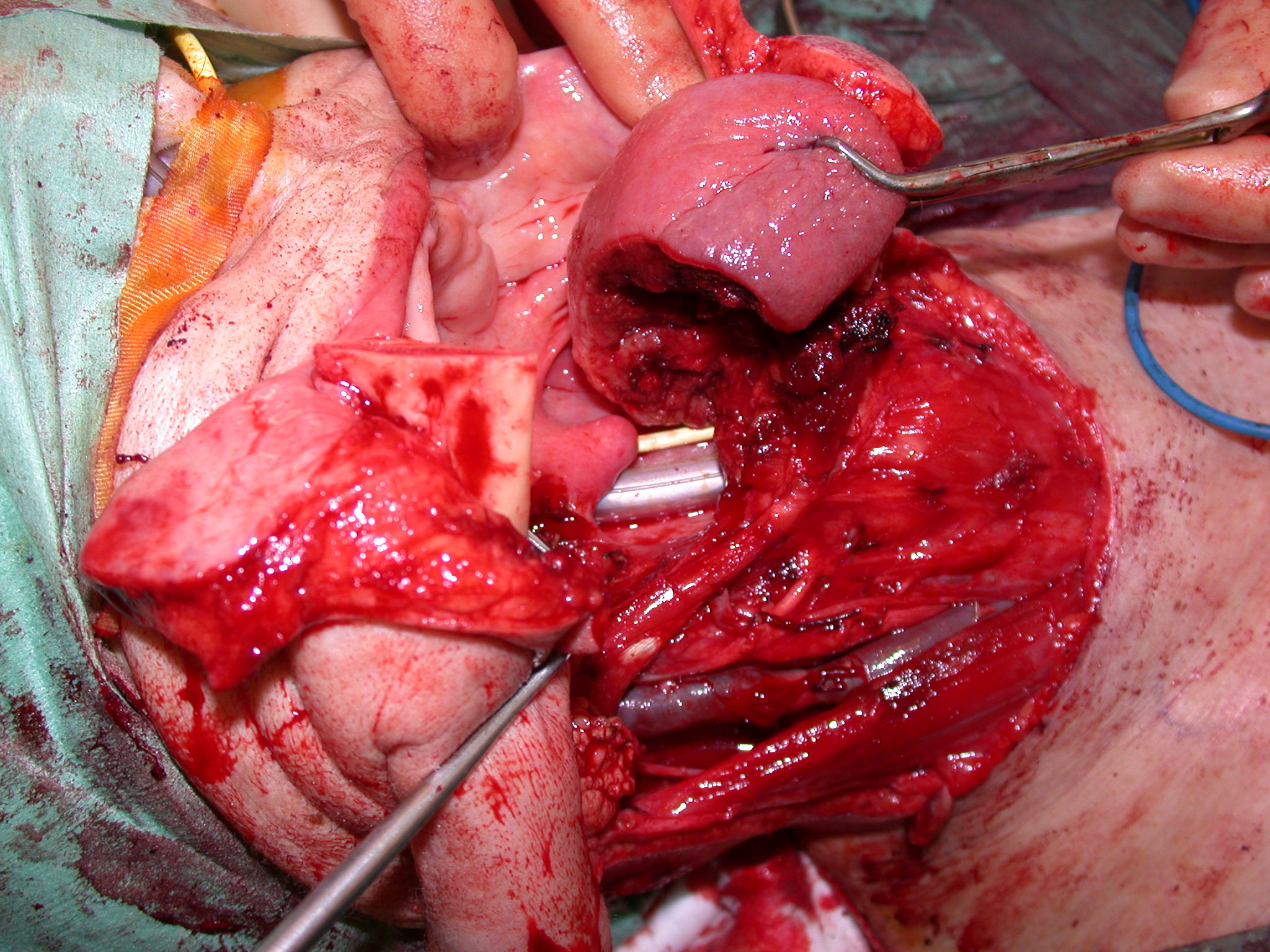

Adequate access is important as the presence of a positive margin adversely affects the outcome. Small anterior oral tumours can be approached through the mouth (peroral or transoral). Where better access is needed, surgical approaches such as lip split and access osteotomy (labiomandibulotomy, see Figure 2) or a visor approach can be adopted.

Tumour resection

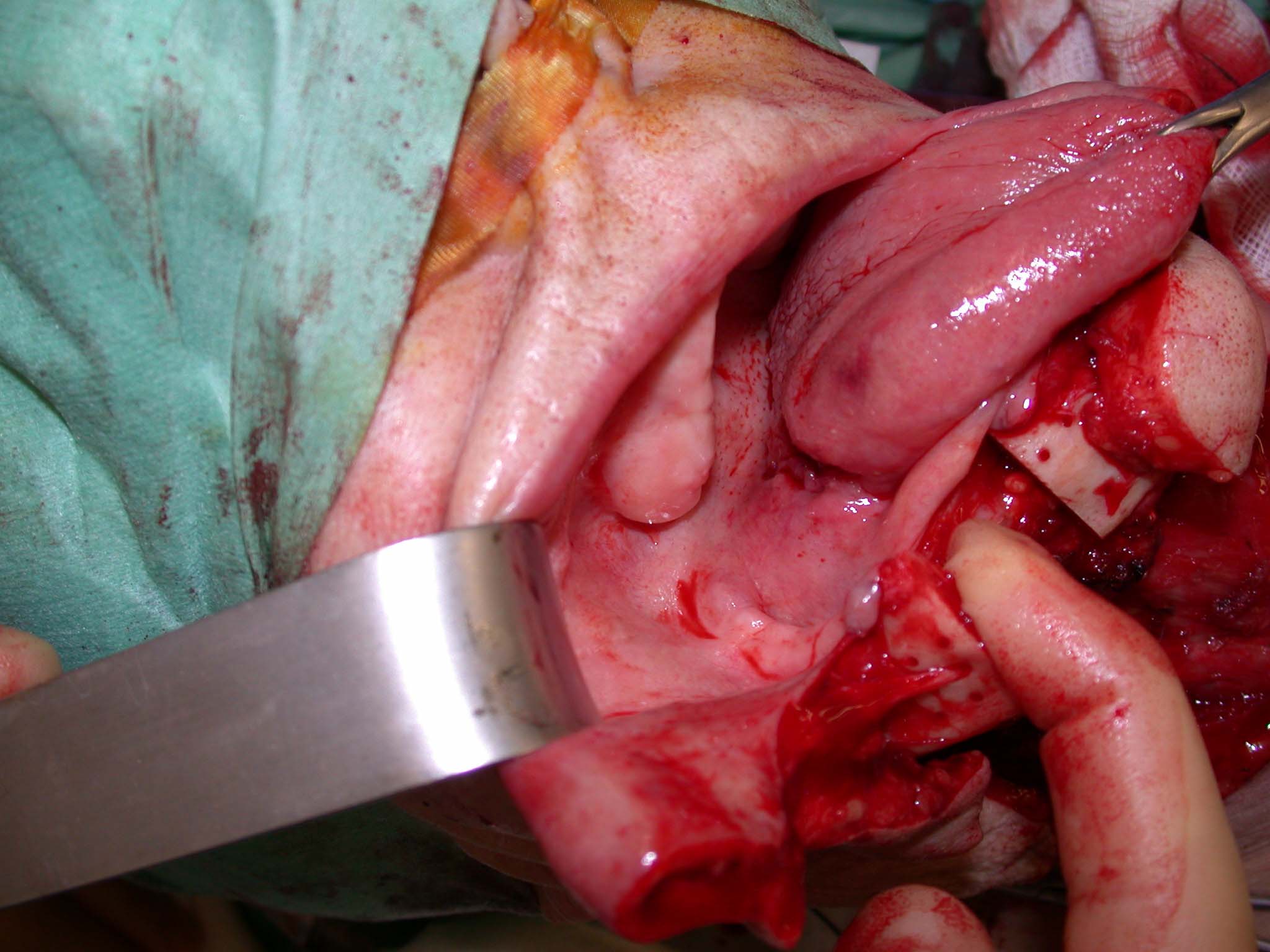

The principal aim of ablative surgery with curative intent is the eradication of local disease by taking a margin of clinically normal tissue from all around the palpable edge of the tumour three-dimensionally. This is usually possible for most tumours. There needs to be a balance between achieving cure with extensive radical surgery at the price of significant mutilation versus an overly conservative approach resulting in insufficient tumour clearance in order to achieve better function. Most surgeons take a 1 cm normal tissue margin all around the tumour. On completion of the tumour resection, some surgeons take small specimens at selective margins for frozen sections analysis. This analysis takes about 20 to 30 minutes. It is, however, dependent on the site(s) sampled. Moreover, frozen section interpretation is never as accurate as definitive histological (haematoxylin and eosin stains) examination, so the risk of false reassurance using this technique is ever present. Figure 3 shows an example of a defect left after resection of an oral squamous cell carcinoma.

Some 70% of oral squamous cell carcinoma occurs in a U-shaped area around the mandible, floor of mouth and tongue. In some instances, lesions close to the mandible can be difficult to assess in terms of bone involvement. If frank invasion has taken place (clinically or on periosteal stripping), then the tumour is likely to have involved the medullary space (central cavity of bone). If the mandible is involved (by the cancer), it will need to be included in the resection. The functional sequelae arising from a segmental mandibular resection with discontinuity of the mandible are considerable, even if the mandible is reconstructed immediately. Where the tumour is close but not involving the bone, a rim of the mandible can be taken, leaving a preserved lower border. The reconstruction is usually simpler and has a better functional outcome.

Certain vital structures need preserving (the common and internal carotid arteries, which have a ca. 20 % risk of stroke if they are ligated, although this can be assessed pre- or even perioperatively, and the cavernous sinus (cavity at the skull base, containing several vital cranial nerves), which is not resectable). Cancers close to or involving such vital structures are usually advanced disease with a poor prognosis. This helps illustrate the need for careful preoperative assessment.

Laser

This method of thermal surgery has a useful role in the treatment of premalignant lesions and early squamous cell carcinoma. A laser beam is used instead of a scalpel for the surgery. The laser beam can be projected in a noncontact manner through a handpiece with a focusing guide length (for example a carbon dioxide laser) or transmitted through a cable and cut on contact (a diode laser).

The laser wound is left unreconstructed (that is ‘raw’). Laser-technology advantages include a haemostatic effect (seals vessels smaller than 0.5 mm), less scarring and oedema and possibly less pain. The wound will epithelialize to leave a virtually normal-looking mucosa.

A similar result can be achieved using fine tip (Colorado needle) cutting diathermy (producing heat locally by means of high-frequency alternating electric current) at significantly lower capital cost. Both techniques share a risk in that the surgical margin suffers from thermal artefacts. The status of the surgical margin is an important prognostic outcome. The presence of a close or positive (tumour present) margin considerably worsens the prognosis.

Transoral robotic surgery (TORS)

There are a small number of surgical robots in the world market. These are inevitably concentrated in the developed world, most obviously in North America. These robots were developed to gain better three-dimensional access to hard-to-reach areas of the body. Unsurprisingly, there has been interest in their use for the treatment of oropharyngeal cancers. Currently at the phase of use and reporting by enthusiasts, it will be interesting to see whether these expensive and complex machines demonstrate benefits to patients in terms of survival and resulting quality of life to balance the obvious costs.

Neck dissection

The treatment, either to prevent spread of cancer to the lymph nodes or to remove established cancer, is some form of removal of lymph nodes. These nodes are present to act as a sieve to both capture and initiate an immune response to the cancer. There are many lymph nodes in the body and there is no evidence that the removal (of up to 100) of these nodes damages the immune response.

Over time views, both scientifically based and in terms of belief and experience of treating clinicians, have changed. Removal of all lymph nodes which carried substantial morbidity for the patient (radical neck dissection, see below) is reserved for extensive, proven spread of cancer to the neck. Selective neck dissection (see below), where only some of the lymph nodes are removed with preservation of other important structures, is used ‘prophylactically’ (when it may – or possible may not be beneficial) and for small nodal deposits. In cases where there is only a suspicion that the cancer may have spread a ‘sentinel lymph node biopsy’ (see below) may be carried out. This involves identifying the lymph node most at risk of a particular cancer spreading to it by radioactive tracer injection. If this node is not involved, no further surgery is needed. If the lymph node is involved, the patient has to return a week or two later to have a neck dissection. Although approved by NICE in the UK, there remains a great deal of uncertainty amongst clinicians about whether or not this is in the best interest of patients as both the logistics and the results have not been definitively established.

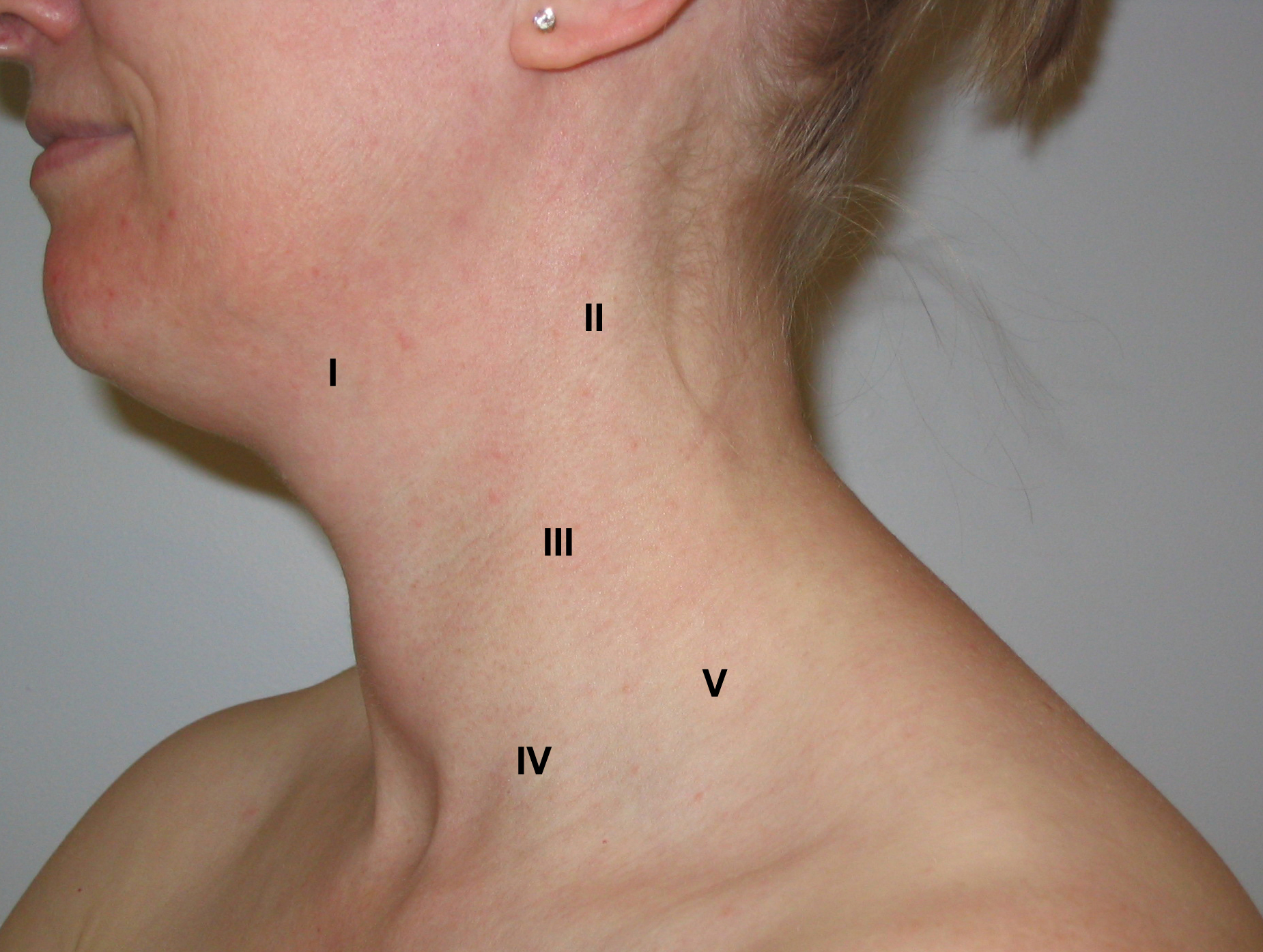

The gold standard technique to achieve regional control of the neck surgically is the radical neck dissection (removal of lymphatics and fat in all five levels in the neck, see Figure 5).

- level I - submandibular and submental nodes

- level II – upper jugular chain from skull base to level of hyoid (small bone below floor of mouth)

- level III – midjugular chain from level of hyoid to lower border of cricoid (cartilage around windpipe, middle of neck)

- level IV – lower jugular chain from cricoid to clavicle (collar bone)

- level V – from posterior sternomastoid (muscle along sides of neck) edge to anterior edge of trapezius (another muscle) from skull base to clavicle.

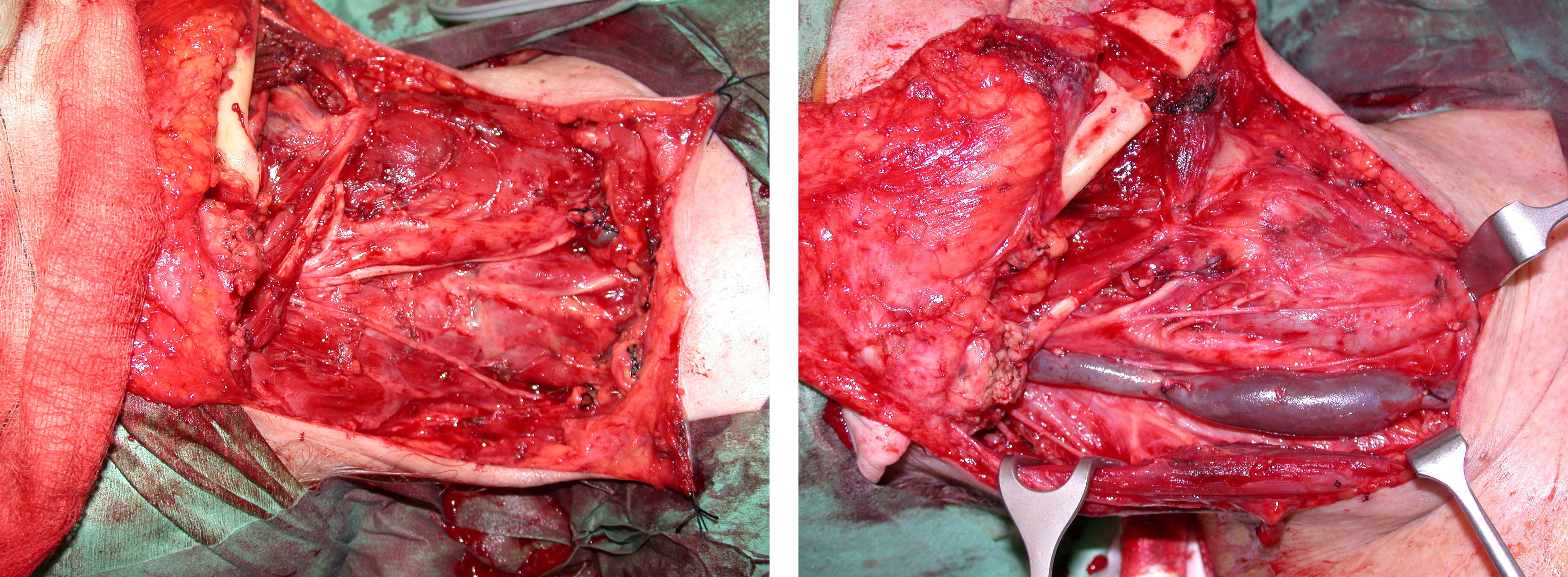

However, there are significant side effects associated with the radical neck dissection (see Figure 6).

Radical and selective neck dissections are illustrated in Figure 7.

The different types of neck dissection have been classified to standardize terminology. The surgical treatment of the neck can be divided into elective and therapeutic neck dissections.

The classification of neck dissections, relevant for oral cancer treatment, distinguishes two main categories:

- Comprehensive dissection (removes all five levels of neck lymph nodes)

- Selective dissection (removes only some of the levels of neck lymph nodes; preserves many structures)

These two categories have subcategories as is tabulated below.

| Comprehensive neck dissection (removes all five levels of neck lymph nodes) |

|---|

| Radical neck dissection (in addition removes accessory nerve, internal jugular vein and sternocleidomastoid muscle) |

| Modified radical neck dissections: Type I (preserves accessory nerve) Type II (preserves accessory nerve and internal jugular vein) Type III (preserves accessory nerve, internal jugular vein and sternocleidomastoid muscle) |

| Selective neck dissection (removes only some of the levels of neck lymph nodes; preserves many structures) |

| Supraomohyoid neck dissection (removes levels I, II and III) |

| Anterolateral neck dissection (removes levels I, II, III and IV) |

| Lateral neck dissection (removes levels II, III and IV) * |

| Posterolateral neck dissection (removes levels II, III, IV and V) * |

*Only used in the treatment of laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancers, not used for oral cancers

The most commonly chosen approach for the neck with negative clinical findings among patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma is selective neck dissection as a staging or therapeutic surgical procedure. The reason comes from Lindberg who demonstrated in 1972 that in patients with carcinoma of the oral cavity (tongue, floor of mouth) the lymph nodes most frequently involved were

- submandibular (level I)

- jugulodigastric (level II)

- midjugular (level III)

The low jugular (level IV) and posterior triangle (level V) lymph nodes were rarely involved. The same study demonstrated that the lymph nodes most frequently involved in patients with carcinoma of the oropharynx were the jugulodigastric (level II) in all sites, including potential bilateral involvement. The nodes of the submandibular or submental (level I) triangles were seldom involved in patients with oropharyngeal carcinomas. Lindberg also noted that the squamous cell carcinomas arising from the base of the tongue frequently metastasised to both sides of the neck.

A retrospective analysis in 1990 by Shah of 1119 radical neck dissection specimens reported the following:

- the submental (level IA), submandibular (level IB), jugulodigastric (level II) and midjugular (level III) lymph nodes were at highest risk for metastases from squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity

- the jugulodigastric (level II), midjugular (level III) and lower jugular (level IV) lymph nodes were at highest risk for metastases from squamous cell carcinoma of theoropharynx, hypopharynx and larynx.

Davidson in 1993 reported a 3 % incidence of histologically positive posterior triangle (level V) lymph nodes in a retrospective study of 1277 neck dissections in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

Elective neck dissection is performed when there is no clinical evidence of involved lymph nodes in the neck. It is a useful staging procedure. These procedures tend to be selective (only taking the high-risk groups of lymph nodes in order to minimise side effects and therefore improve function). As many structures in the neck which are not involved in the spread of malignant disease as possible are retained. Although originally introduced as a staging procedure, the selective (elective) neck dissection, removing levels I to IV has become the therapeutic standard in patients with N0 stage malignancy and low-volume node-positive neck when treating oral and oropharyngeal cancer surgically.

Interestingly this is not universally applied and may reflect the particular UK influence on the role of level IV lymph nodes – anatomical versus radiological definition, relationship to ‘skip lesions’ and consistency in technique and training in ‘selective neck dissection’.

German practice for squamous cell carcinomas consists of a neck dissection of levels I-III as a standard procedure. If the tumour is strictly on one side close to the body of the mandible or the lateral border of the tongue, it is performed only unilaterally and expanded to the other side and level V on the ipsilateral side only in cases of positive lymph nodes, proven by frozen sections. If the tumour is located anteriorly in the mouth or behind the molars, neck dissection level I-III is conducted on both sides and expanded to level V if the frozen sections in level II or III are positive.

This is clearly a different oncological strategy and based on a different premise and available resource (for example ready availability and reliance on perioperative frozen section).

Therapeutic neck dissection is performed when it is strongly suspected, or known, that there is disease in the neck (enlarged lymph nodes by clinical or radiological criteria, or positive findings from fine-needle biopsy). In order to achieve good control, some surgeons may perform comprehensive neck dissection (taking all five levels of lymph nodes in the neck and usually including at least some of the noninvolved anatomical structures; modified radical neck dissections types I to III; see Table 1). However, in small-volume neck disease, it is reasonable to perform selective neck dissection as described above: if postoperative radiotherapy is indicated, the survival and recurrence figures are no different and the morbidity of selective neck dissection is less than that associated with radical neck dissection.

In many maxillofacial surgical oncological practices it is now more common to perform an extended modified radical neck dissection (hyper-radical, including skin or other structures in one area but preserving a viable structure, perhaps the accessory nerve, in another) than the classical radical (block) neck dissection.

A ‘positive neck’ is the one with clinical or radiological evidence of disease in neck lymph nodes. There is no randomised controlled evidence that would clearly define the best treatment for patients with a clinically node-positive neck. Patients with clinical stage N1 disease should be treated by appropriate neck dissection, or by radical radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy. Patients with clinical stage N2 or N3 disease should be treated by comprehensive neck dissection and external beam radiotherapy, or by radical radiotherapy and comprehensive neck dissection. The difference in approach is very variable primarily because of logistics, not evidence. The only agreement is that both modalities together have a higher survival rate.

Elective neck dissection is a controversial area, in particular for early-stage oral cancer. A possible disadvantage of leaving a neck alone and operating only when it becomes involved clinically is that positive neck findings carry a poorer prognosis because the disease is more advanced, a consequence of the detection of disease in the neck often coming when it has reached the N2 stage. The disadvantages of neck dissection include unnecessary surgical morbidity (if found to be negative pathologically), a claimed 1% risk of mortality (this may well be a significant overestimate) and inefficient use of resources.

Alternatives to elective neck dissection (when no disease is demonstrable clinically or radiologically) include a watch and wait policy, close monitoring with regular ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy (problem with follow-up compliance) and, currently on trial, sentinel lymph node biopsy (only investigating the lymph nodes most likely to be affected), though this has been shown to have poor sensitivity in occult disease.

Adjuvant radiotherapy is given to the primary tumour site where there is tumour present at the margins, close to the margins, high grade dysplasia/carcinoma in situ at the margins on histological analysis, bone invasion (stage T4 by definition) or large tumours. Adjuvant radiotherapy is given to the neck following neck dissection where there is extracapsular spread, multiple intracapsular disease (more than two lymph nodes positive) or soft tissue disease or positive margins.