Reconstruction

It is useful to take a systematic look at the theme of maxillofacial surgical reconstruction for an impression of the philosophy, the working and the limitations of this technically highly developed approach to restore form and function. Maxillofacial reconstructive surgery relies heavily on the exploitation of human anatomy and nature’s ingenious ways of incorporating resilience into living systems.

There are two aspects of classification: a systematic view of defects, and a systematic view of reconstructive techniques.

Classification of defects

In addition to the size, location and anatomical complexity, defects can be divided into types of tissue that needs to be reconstructed:

- soft tissue

- bone

- composite

- special tissue (for example, nerve).

In practice, bone defects usually have some soft tissue component involved as well. It is often easier to think of the dominant tissue that is missing in the defect.

Reconstructive techniques

Many different reconstructive techniques are available:

- open wound healing

- primary closure

- grafts

- local flaps

- distant pedicled flaps

- distant free transfers

- prefabricated flaps

- prosthesis.

Open wound healing can be the best option in certain circumstances, leaving a superficial open wound to heal. This includes laser wounds (see Figure 1), as well as some defects in young children.

There is clearly a limit to this option because deep or extensive wounds usually heal slowly with scarring and resulting deformity.

Healing by primary closure is the most common reconstructive method used when the defect is small and the surrounding tissue is slack enough to allow advancement for closure of the wound. It provides the best outcome because the adjacent area provides similar quality tissue without the need for a separate donor site wound. The wound should also heal faster and, apart from suture removal, requires relatively simple aftercare.

Healing by primary closure is not a viable option when there is inadequate adjacent tissue because closure under tension will simply break down.

A graft is the transfer of tissue by complete separation from the donor site to the recipient site. This potentially dead piece of tissue then gains a new blood supply by ingrowth of new vessels from the recipient bed. This process works on the principle that the tissue’s nutritional needs are initially met by fibrin attachment with oxygen diffusion from the plasma of the tissue bed (coined ‘plasmatic imbibition’). Capillary ingrowth with establishment of new vascular supply follows shortly.

A graft can be from the same individual (autograft), from another individual of the same species (allograft) or from a different species (xenograft). Autografts are better for several reasons, including compatibility with the person’s immune system, lower rates of infection and ultimately better outcomes.

A graft can consist of

- skin

- mucosa (lining tissue)

- fascia (strong bands of connective tissue)

- bone

- cartilage

- nerve.

A flap is transferred tissue that has its own blood supply. Reconstruction using grafts (see above) is limited by the need for a well-vascularised recipient site for a graft to ‘take’. A flap is much less dependent on the recipient site for ‘take’ because it brings its own, new, blood supply. The use of flaps with their own blood supply allows more tissue bulk and predictable healing and viability. The greater tissue bulk in flaps can provide better form, structure and character in comparison with grafts. The better the blood supply, the larger and more complex the amount of tissue will be transferable.

A flap can be

- local (using adjacent tissue);

- distant or local pedicled (using remote or local tissue, two-stage procedure, temporarily maintaining a narrow base of tissue with the donor site for continued blood supply before complete detachment from the donor site after an initial period);

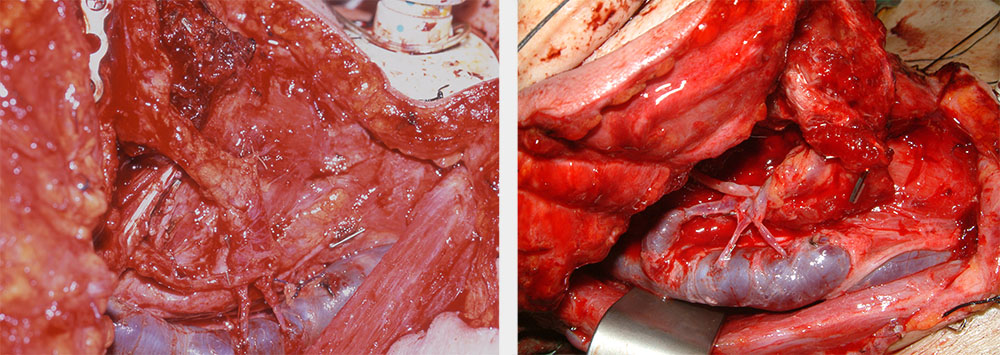

- distant free transfer (harvesting and detachment of tissue with its blood (and sometimes nerve) supply and transfer to the defect site; blood (and nerve) supply for transplanted tissue at recipient site re-established by re-anastomosis (reconnecting) of transferred blood vessels to suitable vessels (and nerves) using microvascular techniques; see Figure 2).

There are two main patterns of blood supply for flaps – random or axial. A random pattern relies on general subcutaneous blood flow. An axial flap supply is based on a specific vascular pedicle. Some flaps feature a combination of the two types of blood supply.

Free flaps can consist of soft or hard (bone) tissue, or a combination of both. Free flaps can be harvested from many different distant body locations.

The following two sections discuss in detail the different types of grafts and flaps and the reconstructive options for different types and locations of defects.

Table 1 gives an overview of reconstructive options for mouth, jaws and face.

Table 1 Options for reconstruction of the mouth, jaws and face

| Options | Advantages | Disadvantages | Indications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leave to heal (open wound) | Simple No donor site |

Contracture, scarring Wound dressings needed |

Superficial wounds Some laser wounds |

| Primary closure | Simple No donor site Linear scar Heal fastest |

Dehiscence (splitting) risk Adjacent tissue distortion |

Small defects with lax adjacent tissue Should be used whenever possible |

| Graft | Relatively simple Skills possessed by most surgeons |

Reliance on healthy bed to take Limited character and bulk (cosmesis) |

Superficial wounds where primary closure is not feasible |

| Local flap | Matching tissue characteristics Ease of harvest |

Can further distort local function if sizeable defect | A popular option for small to medium defects |

| Distant pedicled flap | Large tissue transfer from healthy region |

Poorer tissue match Donor site morbidity Additional larger procedure |

Medium to large defects |

| Distant free transfers | Can tailor best tissue available to suit defect Healthy tissue with good vascular supply allowing better healing |

Complex procedure requiring specialised expertise All or none phenomenon – failure will result in defect remaining Anastomoses (and flap) at risk if patient is unstable medically |

Reconstruction of choice for most significant defects in most patients fit for major surgery |

| Prefabricated flaps | Better flap quality with modification or prefabrication | Extra surgical procedure with prefabrication Can risk flap outcome with previous surgery |

Ideal for traumatic or congenital defects (less suitable for cancer patients with disease progression) |

| Prosthesis | No surgical reconstruction needed Allows inspection of defect for recurrence of malignancy |

Needs expertise of prosthetist Limited by patient’s compliance and dexterity |

Low-level maxillary defects |