Jaw disproportion

Contents

Where surgical intervention is thought to be the best way forward to deal with issues due to disproportionate growth of the jaws, this is purely elective surgery. Extremely careful assessment and diagnosis, underpinning an informed decision based on fully explored potential risks and benefits, plays a major role in these circumstances. Accordingly, below we outline the various general and specific assessments in the process in a little more detail.

Before we start, a brief comment on potentially confusing nomenclature about malocclusions may be useful. There are several terms, definitions and classifications (after E. Angle, the ‘father of modern orthodontics’; early 20th century) in use, all meaning essentially the same condition(s).

Angle class I (neutrocclusion): Normal occlusion of molar teeth but there may be some other issues with ectopic teeth (misaligned or wrongly erupted teeth), spacing or overcrowding issues. These conditions are largely the domain of orthodontics (see below) and will typically not require orthognathic surgery (although some other maxillofacial surgical interventions may be necessary, such as the removal of unerupted or impacted teeth).

Angle class II malocclusion (distocclusion, retrognathism): mandibular hypoplasia, a relatively too small lower jaw, causes this. This class of malocclusion has two further subdivisions, determined by the degree of overlap of the top teeth to the bottom teeth (overbite).

Angle class III malocclusion (mesiocclusion, prognathism, anterior crossbite, negative overjet, underbite): maxillary hypoplasia, a relatively too small upper jaw, or mandibular hyperplasia, a relatively too big lower jaw, can be the cause.

Significant class II and class III malocclusions may benefit from orthognathic surgery. There can be different classes of malocclusion on the left and right sides.

History

A prime reason for taking a detailed history is to identify somebody’s perception of the problem. It is also used to assess somebody’s fitness for surgery. This is entirely elective surgery it is therefore even more essential that any risks associated with the surgery are kept to a minimum.

Occasionally a cause, such as a family trait, congenital deformity, or trauma in infancy is identified, although usually there is no obvious aetiological factor. People present with various complaints. Most are concerned about their appearance; they may also be concerned about their ability to chew, bite or speak.

Occasionally people are referred for orthognathic surgery in the belief that their temporomandibular (jaw) joint (TMJ) dysfunction may be helped by surgery. There is little evidence that the correction of malocclusion can improve TMJ pain or dysfunction. It is inadvisable to promote orthognathic treatment as a treatment for TMJ conditions. People should be aware that pre-existing TMJ symptoms may worsen, persist or improve during and/or after orthognathic treatment, it is entirely unpredictable.

During the assessment all involved, clinicians and patients, must always be mindful of unrealistic expectations. Some people may have excessive concern for minor or imperceptible abnormalities and may produce diagrams or photographs showing how they would like to appear. Some people feel that an operation would improve their relationships or job prospects, providing an instant solution to their problems. To avoid serious problems, disagreements and disappointment later on, a frank and serious conversation at this stage is a reasonable and necessary way forward. It is, however, true that in carefully selected cases, paired with realistic expectations, surgical correction of jaw disproportion can bring about great satisfaction and improved social confidence.

Clinical Examination

The clinical examination should consist of a systematic evaluation approach to both the soft and hard tissues.

Profile

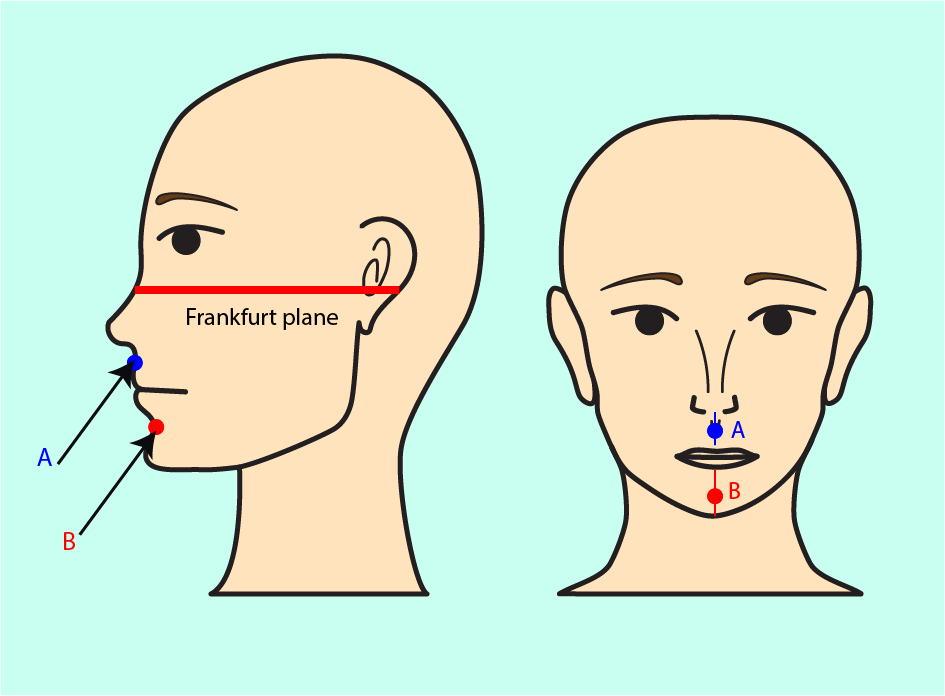

The patient should be sitting comfortably with the Frankfurt plane horizontal (the Frankfurt plane is also called the eye-ear plane, it is a descriptor in craniometry (measurements of the skull). This line, when adjusted as horizontal, corresponds to a posture where somebody is sitting upright such that a line taken from roughly the middle of the ear to the peak position of the cheekbone is horizontal; see Figure 1).

It is useful here to consider the concept of the face being divided into thirds; an upper, a middle, and a lower third. The lower third itself is divided into thirds; the upper lip being one third compared to the lower two thirds, which extend from the lower lip margin (stomion) to the chin margin (menton). Facial aesthetics is maintained when the lower face height is about 50 to 55 % of the total face height, when measuring from nasion (the depressed area on the nose, just above the bridge of the nose and below the glabella (the area between the eyebrows) to menton.

The relation of the maxilla to the mandible is noted (skeletal classification). In the maxilla, prognathism or retrognathism can be diagnosed, as the face will appear more convex or concave, respectively. In addition, the shape and size of the nose are examined.

The nasolabial angle (the angle between the surface of the upper lip, in the middle of the lip, and the inferion (bottom border of the nose) is normally about 90°. Retraction of the upper incisors (front teeth) may open this angle and lead to poorer aesthetics by potentially causing dishing of the lower face and making the nose appear more prominent.

The important horizontal relationship of the maxilla to the mandible is assessed. The most common problems are mandibular prognathism and retrognathism. By examining the maxilla first, apparent mandibular prognathism caused by a hypoplastic maxilla can be ruled out (see Figure 3). Some clinicians place cotton wool under the upper lip to mimic maxillary advancement. Similarly, the surgical correction of a retrognathic mandible can be visualized by posturing the mandible forward by the desired amount.

Some points to consider at the planning stage include:

- advancement of the maxilla increases upper incisor show;

- the alar base cinch suture (suture at the base of the nose)

- controls the transverse dimension of the alar base

- improves tip projection

- maintains the thickness of the upper lip

- decreases shortening of the upper lip;

- nasal tip moves relative to A point (see Figure 1) in a ratio

of approximately

- 1: 3 for Le Fort I osteotomies

- 1: 2 for Le Fort II osteotomies

- 1 :1 for Le Fort III osteotomies;

- chin, soft tissue-pogonion moves approximately 1 : 1 with either mandibular advance or setback;

- lower lip moves approximately

- 85 % of the skeletal move in advancement

- 60 % of the skeletal move in setback.

The data compiled in Table 1 can be used as a guide of common dimensions.

Table 1 Measurements used in orthognathic assessment

| Anatomical area | Measurement |

|---|---|

| Intercanthal width | 34 +/- 4 mm |

| Alar base width | 34 +/- 4 mm |

| Interpupillary distance | 65 +/- 4 mm |

| Upper lip length | 22 mm (males), 20 mm (females) |

| Lower lip length | 33 mm (males), 30 mm (females) |

| Upper incisor (front teeth) show | 0 - 3 mm (at rest), 7 - 10 mm (smiling) |

| Nasolabial angle | 90 - 120° |

| Labiomental angle | 115 - 135° |

| Lower face height | 66 mm (males), 60 mm (females) |

| Mid face height | 66 mm (males), 60 mm (females) |

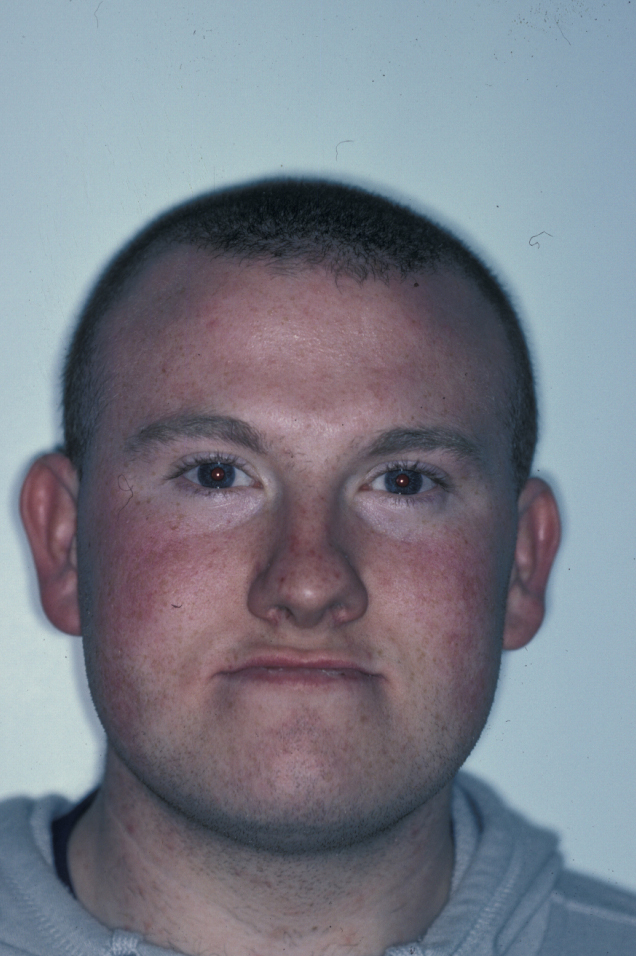

Full Face

Any asymmetry of the face is examined, including the level of the eyes. This is the time to compare facial and dental midlines, which can then be transferred to the study casts (see below). Any cant in the occlusal plane can be confirmed by placing a wooden spatula transversely between the teeth. Lip seal and incisor show both at rest and smiling should be measured. Over- or underbite can be measured directly, see Figure 4. This allows assessment of any excessive incisor or gingival (gum) show, an important baseline in surgical planning.

Intraoral Examination

The molar and incisal relationships are examined visually and are formally documented by photographs (see Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 for examples) and study models (see below).

A thorough dental examination should take place, especially noting oral hygiene and carious teeth. Routine dental care must be completed first, by the general dental practitioner.

Radiographic examination

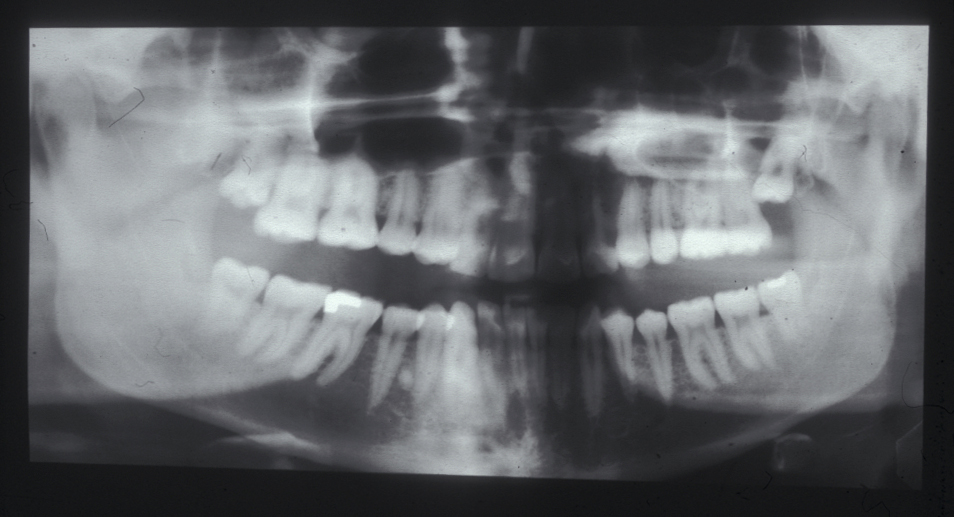

A series of standardized radiographs are studied as part of the assessment.

A panoramic radiograph, OPG, (orthopantogram; also referred to as a dental panoramic tomogram (DPT) reveals caries and periodontal disease, unerupted or impacted teeth, and the presence of coincidental pathology, such as cysts (see Figure 8 for an example).

A lateral cephalogram (a profile side-view X-ray image of the skull and soft tissues) is required. This view supplements clinical analysis with cephalometric analysis (a range of measurements of the head and skull). See Figure 9 for an example of a lateral cephalogram.

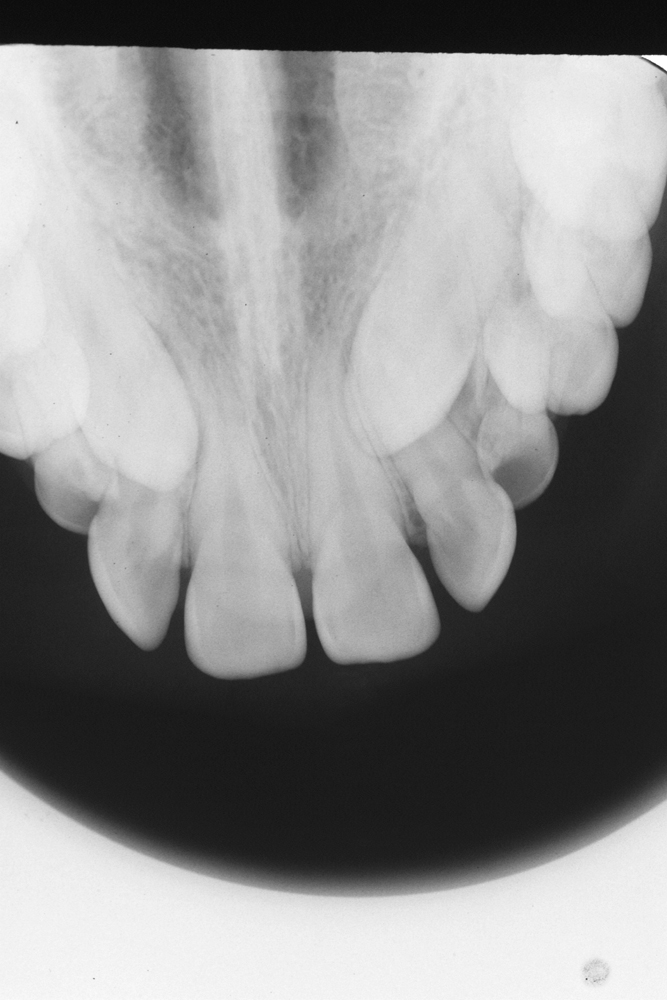

Intraoral radiographs are taken as needed, there are various such views (on intraoral films). The upper anterior occlusal radiograph is the most commonly used. This view uses an imaginary plane to focus on the maxilla and upper front teeth. It is essential for the assessment of unerupted canine teeth. Figure 10 shows an example of an upper anterior occlusal radiograph.

Cephalometric analysis is, in essence, the interpretation of measurements of the skull and facial bones using agreed angulations and linear distances to aid in determining the underlying aetiology of a particular problem. Many analyses exist with varying degrees of complexity. Some have a specific set of indications for use. However, most clinicians will favour a few analyses with which they will be familiar.

It must also be remembered that any such analysis is based on modelling assumptions and/ or small sets of model data. Thus, it is important to remember that a patient is being treated and not a radiograph. Whichever analysis is used, it is only a guide, even if the software used produces impressive-looking pictures.

Photographs

These usually consist of a standardized set of images. Extraoral photographs include the full face at rest and smiling, three-quarter left and right side views of the face, and a profile. Intraoral photographic views should show anterior (front) and buccal (side) teeth in occlusion.

Some clinicians like to construct a montage using the lateral cephalogram (see above) and profile photograph in a 1 : 1 ratio. This tries to mimic postsurgical soft tissue movement. This technique, like computer generated programmes which purport to simulate the variable impact of surgical movement of the jaws, has limitations and must be used with caution in order to avoid unrealistic expectations.

Study Models

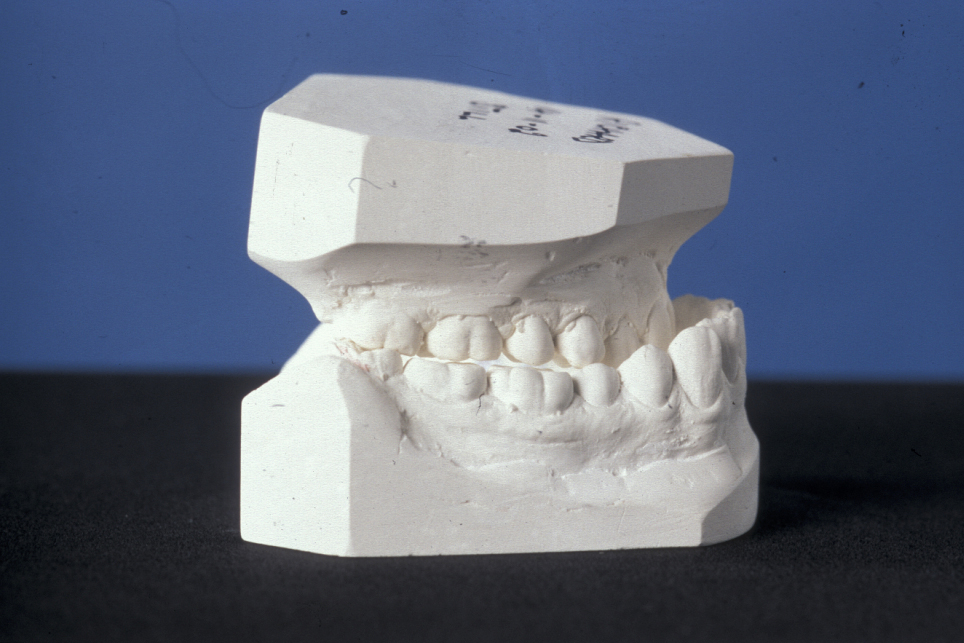

Records are taken at various stages of treatment, usually before and after orthodontic treatment (see below), before and after surgical treatment, and at review appointments at yearly intervals for up to five years after treatment. These records are combined with a record of the occlusion in the form of a wax squash bite (see Figure 11).

The models are trimmed in a standardized manner. On the models, markings can be made (for example, the facial midline in relation to the dental midline). Models can be taken at various stages of treatment, and are used for differing reasons (for example, clinical records, orthodontic planning, and model surgery).

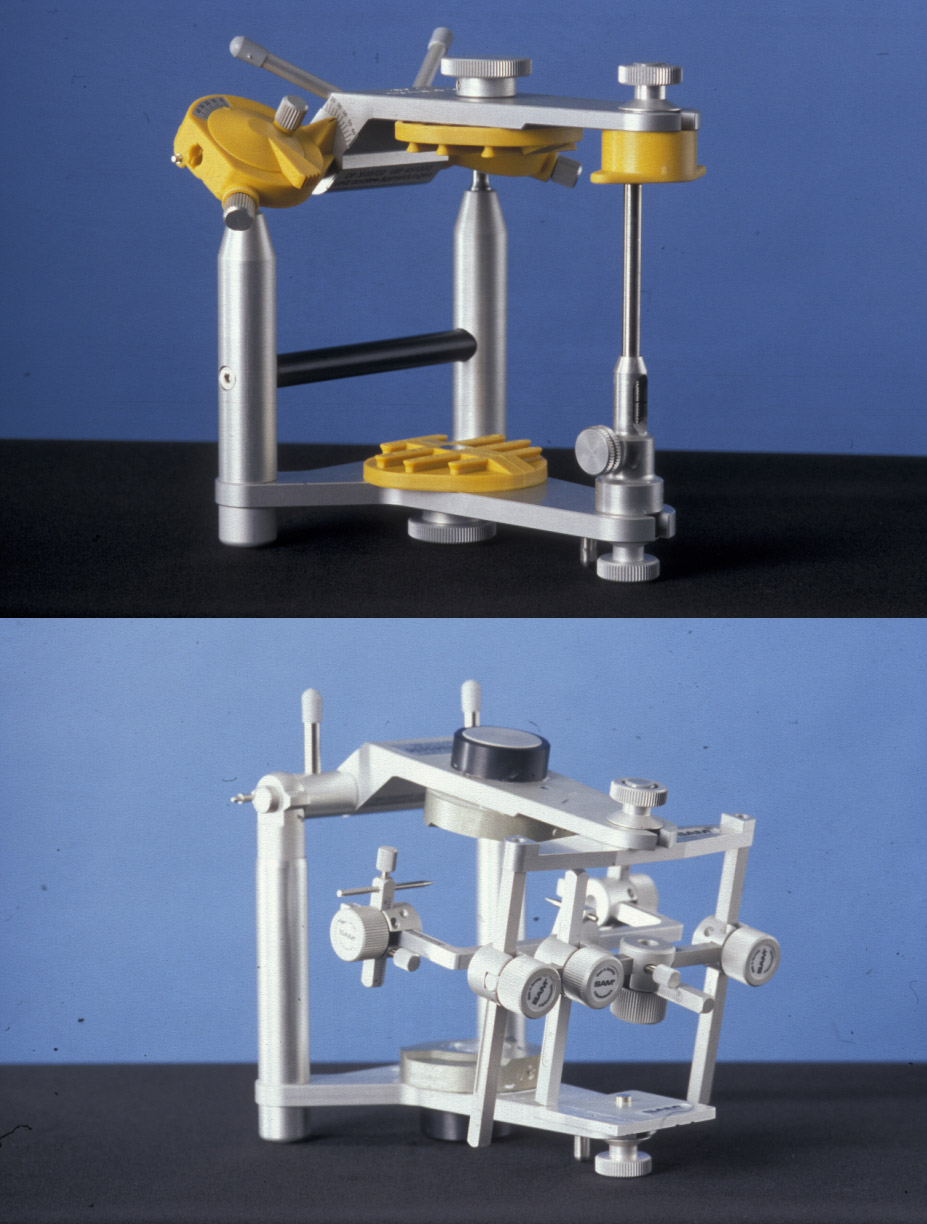

Prior to the orthognathic surgery, a facebow recording is made (see Figure 12). A facebow is a device to essentially translate geometric measurements on the face / head to a mechanical device, an articulator (see below).

The most recent study models are mounted on a semi-adjustable or fully adjustable anatomical articulator (see Figure 13). An articulator is a mechanical device where all parts can be moved in a reproducible manner in all three dimensions. These models are duplicated for the fabrication of occlusal wafers, which are essential for the perioperative localisation of the maxilla in bimaxillary procedures.

Model surgery is performed to gauge whether a satisfactory occlusion is attainable. Model surgery also gives a measure of the required surgical movements (see Figure 14).

Orthodontic treatment

The presurgical orthodontic phase is designed to place the teeth in their correct final position over the dental bases prior to surgery. This involves the correction of dental alignment (see Figure 15), arch levelling, decompensation of teeth in all three planes of space and arch coordination.

It is essential that both the patient and the orthodontic and surgical team are clear about this phase because orthodontic decompensation prior to surgery will make the occlusal relationships significantly worse. The presurgical orthodontic phase can last between 12 and 18 months (Figure 16).

It would be utterly inappropriate for a patient to then decide they did not want surgery as all the preceding treatment would have been moving the teeth in the opposite way from that used by orthodontic camouflage (orthodontic corrective treatment only) (Figure 17).

Postsurgical orthodontic treatment involves final detailing of the occlusion and should be kept to as short a period of time as possible.