Facial appearance

Contents

Below we give a brief description of some aspects of the most common procedures in aesthetic facial surgery:

- rhytidectomy;

- blepharoplasty and related procedures;

- otoplasty;

- rhinoplasty;

- genioplasty and related procedures.

Rhytidectomy

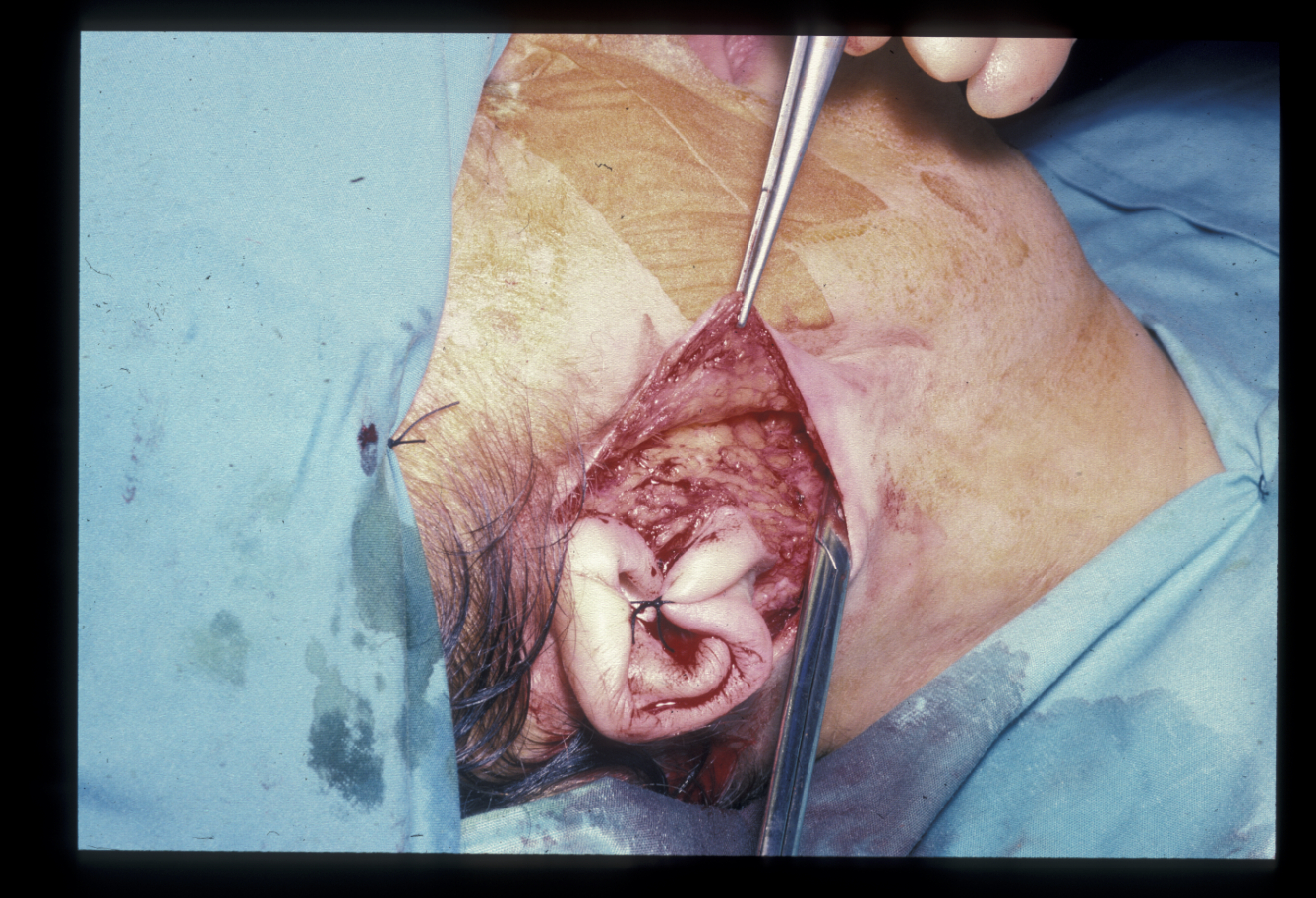

Rhytidectomy (face lift) involves an incision as illustrated in Figure 1.

The incision is made preauricularly (in front of the ear), underneath the lobule of the ear, over the posterior (back) aspect of the pinna (external part of the ear) and extended into the hairline at a right angle to it. A plane is formed in the subcutaneous (under the skin) fat (Figure 2) and extensive skin flaps are raised. These extend to the midline of the neck and to the modiolus of the cheek (a set of muscles located to the side and slightly above the angle of the mouth).

The sagging and ageing of the superficial muscular aponeurotic system (SMAS), a subcutaneous tissue layer, may be addressed by dissecting out the SMAS layer as separate flaps, dissecting it with the skin flaps, or not dissecting it but rather hitching it up and suturing it to the temporal fascia (a strong fibrous tissue layer in front and slightly above the ear) with nonresorbable suture. The flaps are pulled upward and backward (separate SMAS flaps allow a differential pull) and excess skin is excised.

Facelift procedures for the lower face and midface

The standard two-plane lift involves the elevation of a skin flap of variable length from preauricular and temporal incisions. After elevation of the skin flap, a SMAS flap is elevated, typically from below the zygomatic arch (cheek bone), then preauricularly, lateral to the anterior (front) border of the parotid gland (salivary gland in front of the ear), usually extended past the ear lobe and continued as a platysmal flap (the platysma is a flat sheet of muscle that runs from the collar bone to the angle of the jaw). The SMAS flap can be extended medially 3 to 5 cm, sometimes a little further along the jowls. More superiorly it ends before the level of the lateral border the zygomaticus major (the ‘smile muscle’, the muscle that pulls the angle of the mouth upward). SMASectomies and plication of the SMAS and platysma are common. The results of this approach are excellent for the jowls and the lower face, but they do little to restore a more youthful appearance of the midface.

The advocates of the extended superficial musculoaponeurotic system flap claim that by extending the SMAS flap medially well over the zygomaticus muscles, longer-term improvement can be achieved for the nasolabial fold and consequently the appearance of the midface. Although injury to the facial nerve branches of the zygomaticus muscles is unlikely, branches to the upper-lip orbicularis (the muscle that closes the mouth) are vulnerable under the malar fat pad (beneath the skin and the subcutaneous fat layer; see below). The SMAS is often so thin medially that postero-superior traction on it accomplishes little.

A two-plane lift with additional mobilisation or suspension of the malar fat pad requires a relatively extended skin flap to be elevated to reach and mobilise the ptotic (drooping) malar fat pad. It is repositioned and suspended with sutures to the temporal fascia. Problems are encountered with this method because of disruption of suborbicularis planes (near the rim of the eye socket and slightly above the ridge of the cheek bone) leading to prolonged oedema and possible distortion of the lateral canthus (where the upper and the lower eye lids meet at the outer corner of the eye). This operation has good long-term results but is not without risks.

In the extended supraplatysmal plane skin flap, a long, thick skin flap is elevated off the SMAS-platysma complex, thus leaving all the fat attached to the skin flap. In practice, this becomes difficult medially where the SMAS thins out. All the facial retaining ligaments are released and the skin flap is elevated. The SMAS and platysma are also generally plicated for additional support. Or, if thick enough, a SMAS flap or SMASectomy can be performed. The malar fat is in theory elevated, attached to the underside of the skin flap.

The deep plane or composite lift is essentially an extended SMAS flap technique but leaving the skin attached to the SMAS. This long, thick skin muscle flap is closed under tension. The neck flap and the face flap do not connect over the mandible, unlike in most traditional two-plane lifts. There are real risks of complications, including facial nerve neuropathy, long term skin discolouration, an ‘over-operated’ look and lengthy recovery.

The subperiosteal lift is primarily directed to the midface. In brief, the periosteum (layer of dense connective tissue enveloping bones) is elevated off the cheek bone. Once it is released inferiorly, the periosteal flap with all the overlying upper lip levator muscles, SMAS, malar fat pad and skin is repositioned more superiorly and posteriorly, thereby bringing the malar fat pad into its former position. There are variations of the technique (subciliary or intraoral incision, usually endoscopic subperiosteal temporal lift).

There are several other, simpler face-lift techniques, including

- Webster lift (shorter skin flap, simple plication),

- S-lift (short skin flap, small incision, simple plication);

- suspension lift (using sutures made from stretched polytetrafluoroethylene fibres);

- minimal access cranial suspension (MACS) lift (provides jowl correction);

- minimal preauricular access lift.

There are further, non-surgical procedures to achieve some degree of facial rejuvenation.

Blepharoplasty and related procedures

Blepharoplasty (eye lid correction) deals with sagging or puffy eye lids. Bags under the eyes are related to problems with fat distribution around the eyes, rather than lax skin. The incision for lower lid blepharoplasty is shown schematically in Figure 3.

The incision runs just under the lashes and extends out laterally in a crow’s foot. A musculocutaneous (skin and muscle) flap is raised, revealing the orbital septum (a thin but discrete layer between the lining of the orbital bone and the eyeball) and underlying fat. There are three fat pads: larger central and medial ones, a smaller lateral one. Where there is a prominent nasojugal groove (a groove in the region between eye lid and cheek), the fat is re-draped to fill this groove and even out the bagginess of the lower lid. Otherwise, the orbital septum may simply require tightening. This is achieved by bipolar diathermy burns that induce pinpoint areas of fibrosis (scarring) and tightening. Fat removal should be minimal because excessive fat removal can lead to a sunken appearance, which is difficult to correct. Skin removal should also be minimal.

In contrast to the lower eye lids, upper eye lid bagginess is largely the result of excess skin. Figure 4 illustrated the incision for upper lid blepharoplasty for the removal of excess skin.

Immediately postoperatively the eye lids will not meet, but this will settle in about two weeks. In addition to skin removal, a small amount of muscle may need to be removed. As with the lower eye lids, there may be a small amount of fat herniation that may require reduction, but there is no lateral fat pad (rather this is the lacrimal (tear) gland, and it should be left well alone).

In order to address sagging eyebrows, a number of different brow lift procedures and incisions are used, including

- Coronal incision – this incision is made well into the hairline (4 to 5 cm) and a strip of scalp is excised. This procedure tends to lengthen the forehead.

- Pre-trichial incision – this incision is made at the hairline, and scalp is excised. This tends to shorten the forehead. It can result in an abrupt change from skin to hair, thus giving a slightly artificial appearance.

- Midforehead incision – the incision is within the forehead and is suitable for people with deep rhytids. It shortens the forehead, and there will be a visible scar that will be red for a year or so.

- Direct brow pexy – this simply excises tissue directly above the eyebrow. Again, there will be a noticeable scar. This procedure is particularly indicated for people with damage to the temporal branch of the facial nerve.

- Endoscopic brow lift – five small incisions are made within the scalp, and subperiosteal dissection is carried out endoscopically. The scalp is pulled posteriorly and fixed to the skull with screws, which are removed after a few weeks. Although it can potentially lengthen the forehead, this approach is very popular.

Otoplasty (pinnaplasty)

There are various techniques for the correction of prominent ears, depending on the underlying cause.

In the technique of anterior scoring, skin is excised in the posterior pinna after assessing the amount of reduction required. The skin excision is purely to remove the excess that will be left at the end of the procedure. The cartilage is incised and dissected off the anterior skin. The cartilage is then scored parallel to the long axis of the pinna, and further scores may be made at right angles to these. This procedure allows the intact posterior elastic cartilage to pull the pinna back, thus creating a rounded natural antihelix (the thick vertical ridge of the ear). The pinna will be lying at a more natural angle and can be sutured into position.

An alternative is to thin the cartilage posteriorly with a burr and suture the cartilage to the mastoid process (an area behind the ear). This has the advantage of avoiding dissecting the skin over the anterior surface of the cartilage, but it works against the natural logic of using the elastic fibres.

An alternative, well established technique is direct suturing using permanent mattress sutures (traditionally white silk) to recreate the antihelix. An excessive concho-occipital angle (the angle between the bone behind the ear and the cup of the ear) can be reduced by excision of the appropriate of cartilage from a posterior approach (Figure 5, Figure 6).

Rhinoplasty

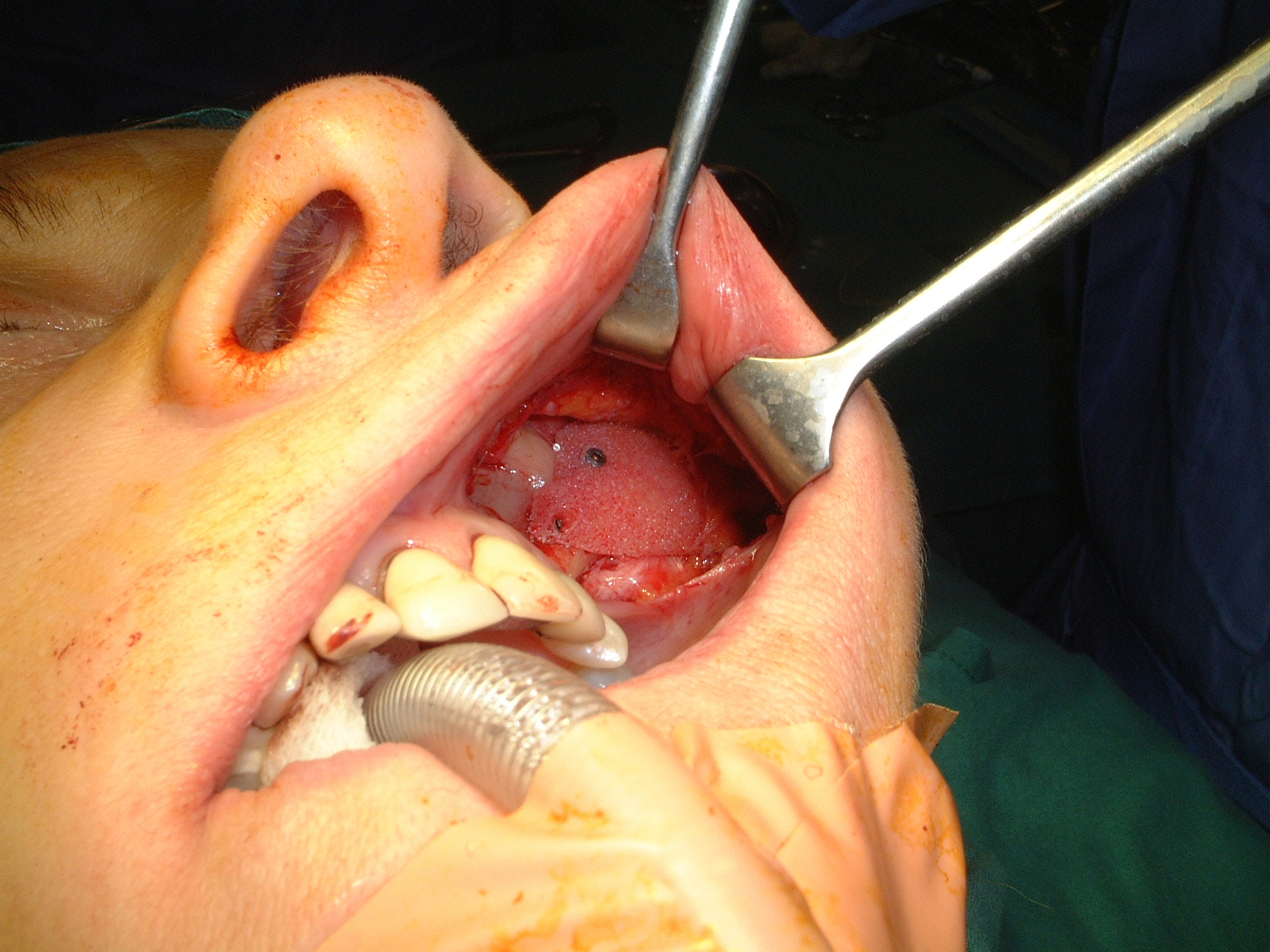

Vast arrays of incisions may be used in performing a rhinoplasty. However, there are essentially two approaches – open or closed. The closed approach remains the most popular method. It involves intranasal incisions either through the alar cartilages, or between the alar and the upper quadrilateral cartilages with a connecting preseptal transfixion incision (incision through both sides of the septum; Figure 7).

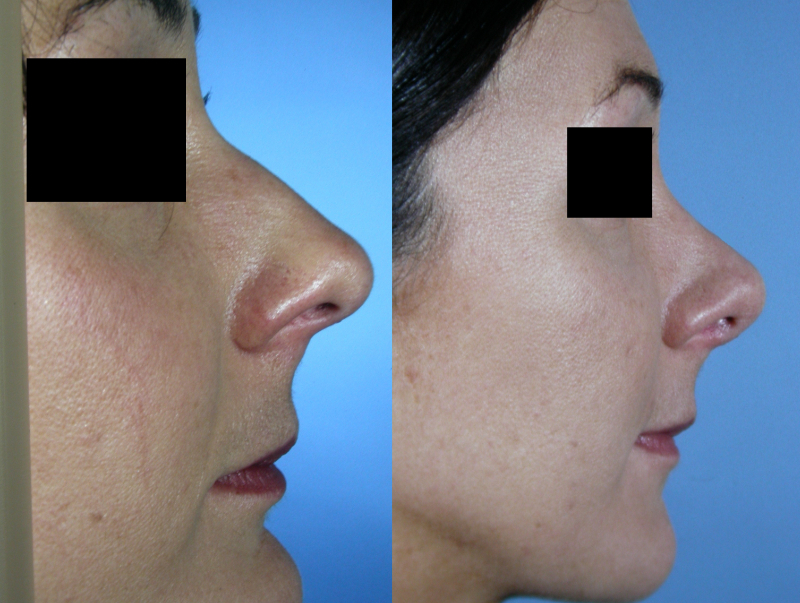

An open rhinoplasty leaves a small scar across the columella, whereas a closed rhinoplasty does not. The bony surgery usually involves removal of a dorsal hump (if present), thus leaving an ‘open roof’. Lateral osteotomies from the piriform aperture (opening in the skull, creating the nasal aperture) along the junction of the nasal bones to the maxilla allow this to be closed to leave a narrower dorsum with a smooth, straight profile (Figure 8).

The alar cartilages may require attention if the nasal tip needs to be addressed. This usually involves either trimming of the lower lateral cartilages or suturing the medial crura (structure extending below the septum and forming the columella and part of the nose tip).

Options for increasing tip projection include

- tip sutures – this procedure involves the removal of any intervening interdomal tissue and suturing the middle crura to one another;

- columellar strut – this places a cartilage strut into a pocket between the medial crura of the lower lateral cartilages to provide a supporting structure;

- tip graft – when even further increased projection is needed, an onlay graft can be sutured over the tip.

Options for decreasing tip projection include

- medial or middle crural release – this procedure is used for minimal deformity: release of ligaments and placement of sutures between the middle crura and caudal septum sets back the lower lateral cartilage complex to a certain degree;

- cephalic trim – this procedure is the excision of a portion of the cephalic margin of the lower lateral cartilage and thus disrupts the support of the nasal tip. A medial crural-septal suture may be used to secure the tip in a more posterior position.

Increasing tip rotation by a small amount may be achieved by simple excision of the cephalic border of the lower lateral cartilages.

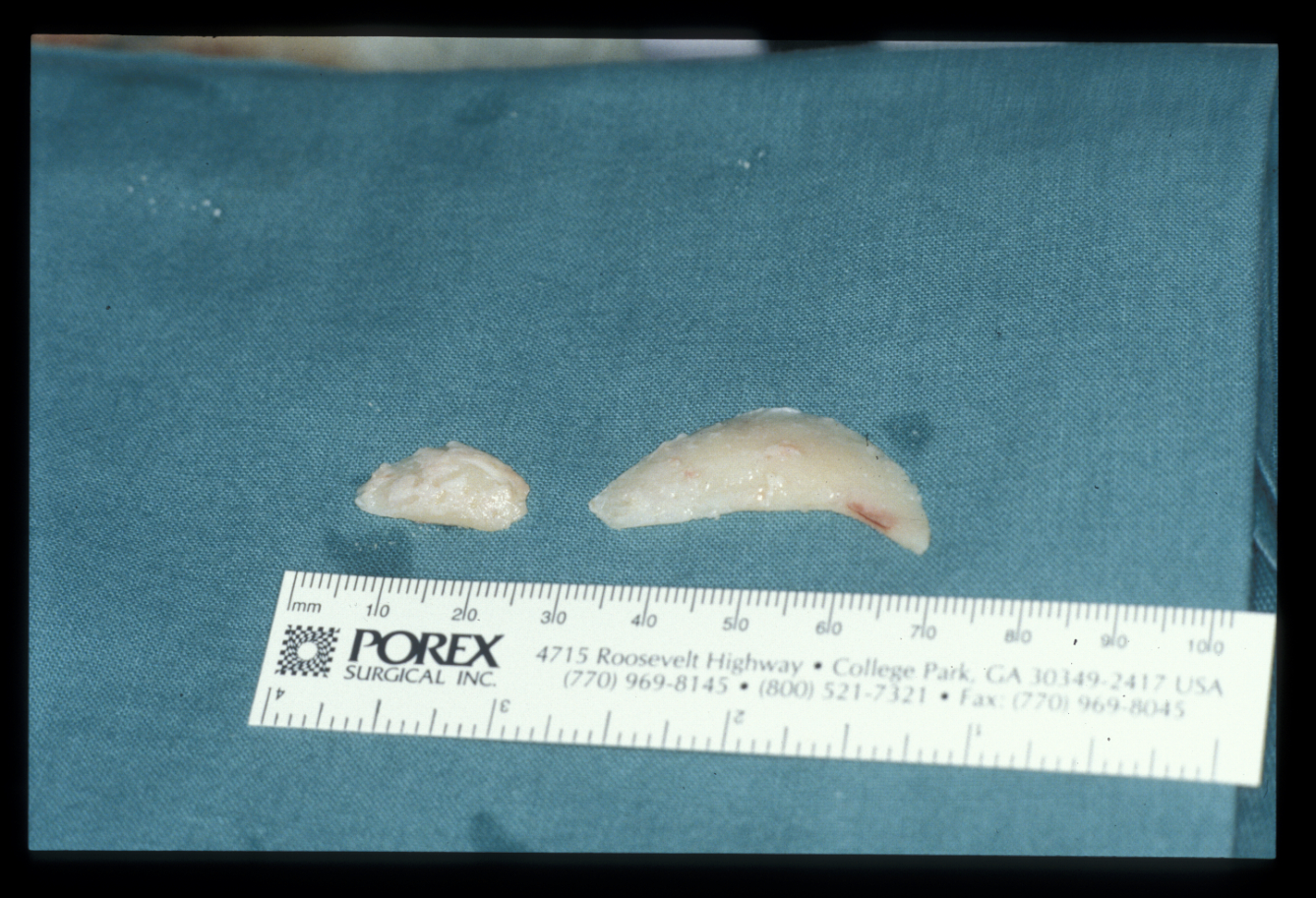

Decreasing tip rotation involves harvesting a septal extension graft of cartilage from either the septum or the rib, and fixed to both the dorsal septum and medial crura. This will serve to push the tip inferiorly and derotate the nose. The tip may be reduced or a submucous resection of the cartilaginous septum may be carried out. Straightening a deviated cartilaginous septum is difficult.

Where tissue is required to be added rather than removed, a graft from the pinna or septum can be used, for example to augment the dorsum or the projection of the nasal tip. Much time is spent discussing the best form of postoperative dressings and support, but the actual tissue manipulation is the crucial component of these interventions (Figure 9).

Genioplasty

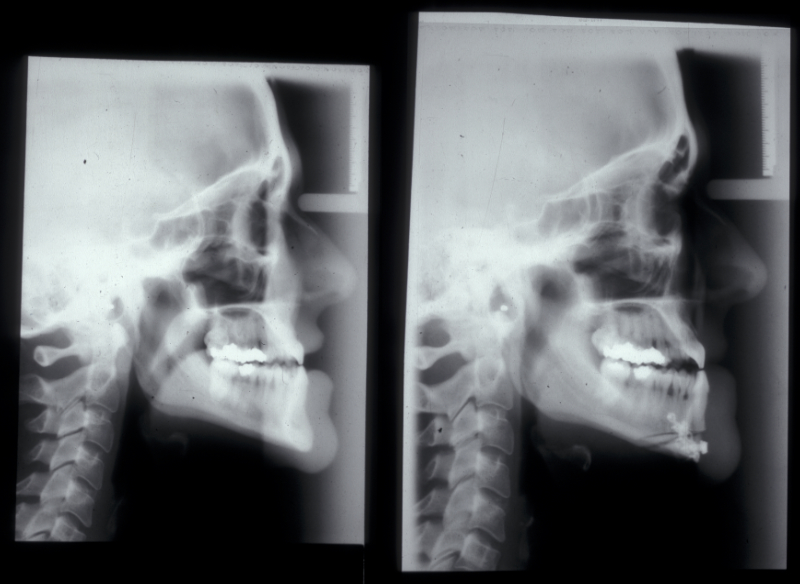

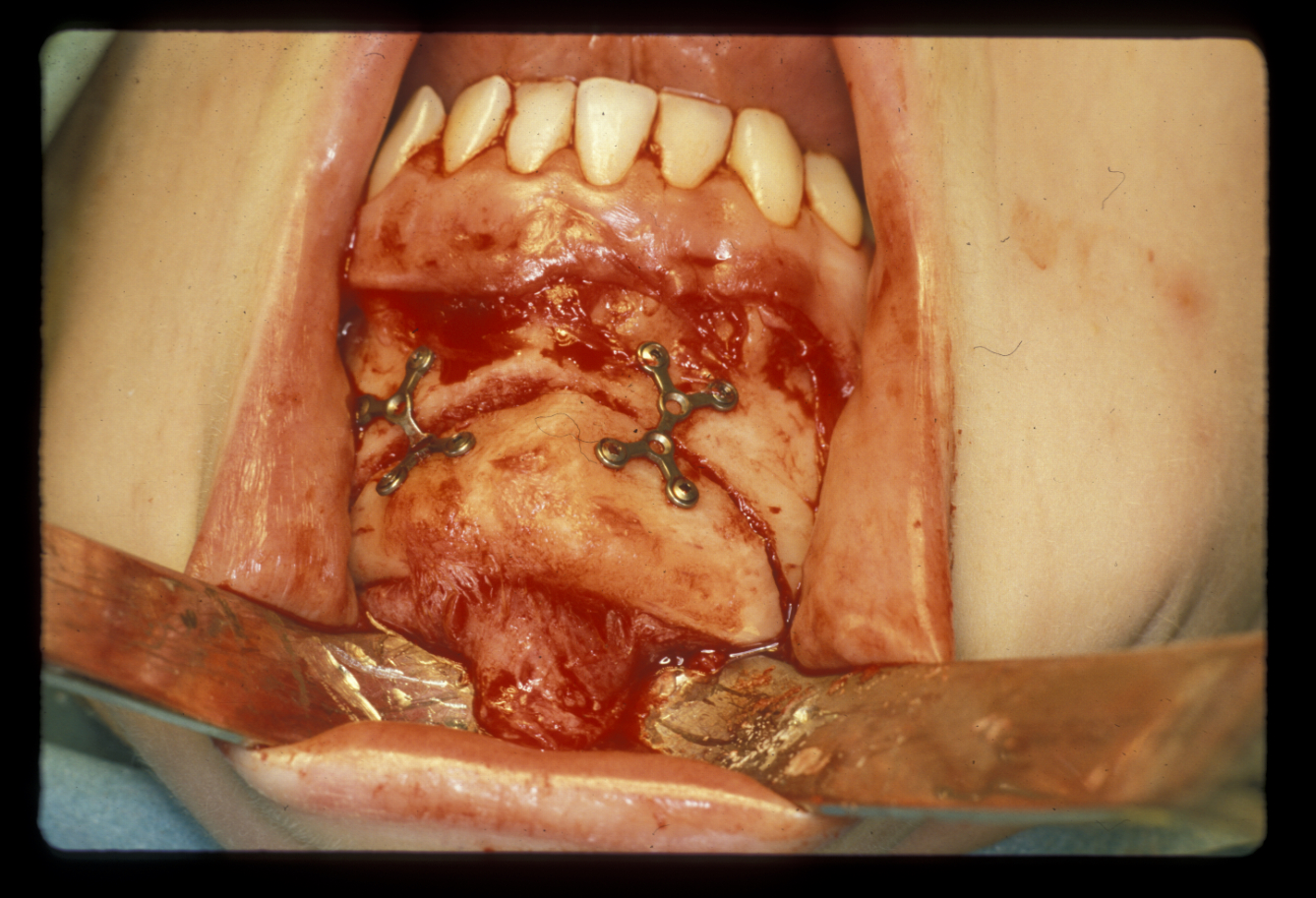

Genioplasty procedures use very similar principles to those of orthognathic procedures (Figure 10).

The chin is approached from an intraoral incision that exposes and protects the mental nerves. Bone cuts are made horizontally to retain the lingual muscle attachments. The chin is reduced by excising a middle portion of bone and inset to preserve the aesthetics of the cortical chin shape. It can be advanced by sliding forward. It is internally fixed using miniplates (Figure 11). Small asymmetries can be corrected in this way.

Augmentation genioplasty uses implants, either made from synthetic materials or a bone graft taken from the hip. The implant can be inserted by a skin incision under the chin (which is invisible from a front view) which is preferable for inert non-biological implants which have a lower inherent resistance to infection. Iliac crest grafts or sliding advancement genioplasties are far more common and a number of specific intra-oral miniplates have been devised to aid this surgery which also has a role in managing obstructive sleep apneoa. Almost inevitably, the aesthetic results using somebody’s own bone are superior to those achieved by using synthetic materials.

Genioplasty approaches, are used to correct other facial contours as well. If facial contours appear excessive because of underlying bone, this can in part be corrected by osteotomies (Figure 12).

This is particularly important in those areas where reduction of the outer cortical shape may result in a distorted contour (Figure 13).

It should be borne in mind that the postoperative appearance is unpredictable. There is not a 1 : 1 relationship between bone removed and reduction in final soft tissue contour. Similarly, where there appears to be a soft tissue deficit, alloplastic onlays may be employed for augmentation (Figure 14).