Ectopic (displaced) teeth

Contents

Impacted or ectopic teeth

Although any tooth may become impacted (its path of eruption is obstructed), those affected commonly are the lower third molars, upper canines, upper second premolars and upper incisors. These teeth may also be ectopically placed (their follicle develops in a remote position). Untreated, many impacted or ectopic teeth cause no problems and remain largely asymptomatic. However, a significant number may either develop complications or, if an anterior tooth is affected, may cause aesthetic or functional problems.

If a decision is taken not to undertake active intervention, the affected tooth must be kept under close observation, both clinically and where appropriate radiographically. Complications of impacted or ectopic teeth include:

- prevention of eruption of adjacent tooth;

- cystic change in associated follicle, a rare occurrence;

- resorption of adjacent teeth with loss of vitality; this most commonly occurs with upper canines resorbing the roots of upper lateral and central incisors. Initiation of this process is however extremely rare after 15 years of age.

In view of these rare complications, the value of routine radiographic screening of impacted or ectopic teeth is controversial, especially in view of recent radiation exposure guidelines. As complications are relatively rare the benefit of repeated radiographs is limited. Therefore, the decision to regularly radiograph such teeth is a difficult one, especially if they have been quiescent and asymptomatic for a number of years.

If ectopic or impacted teeth are partially erupted then they are at risk of the usual complications, particularly if their position prevents adequate oral hygiene measures:

- advanced caries;

- periodontal disease.

Third molar teeth (wisdom teeth)

The commonest cause for failure of a tooth to erupt is lack of space into which it can pass. Other reasons include malposition of the follicle or congenital absence. Rarely other associated pathology such as cysts, odontomes (irregularly grown dental tissue) or tumours will prevent eruption. Treatment is then directed at this underlying pathology. Developmental conditions such as cleidocranial dysostosis (a congenital condition affecting mostly bones and teeth) or cleft lip and palate are associated with an increased incidence of unerupted third molars. In the presence of an obstruction (such as another tooth), the unerupted tooth is said to be impacted.

Third molars normally erupt between the ages of 17 and 21 although later eruption can occur. Because they are the last teeth to erupt, they have the least space available and therefore they commonly impact. Soft western diets have also been implicated, as the absence of attrition between the adjacent lower teeth does not provide any additional space for the teeth to erupt into. It is often possible to assess the potential for eruption by the age of 16 on the basis of clinical examination and the use of radiographs.

Prophylactic removal of third molars is no longer considered justifiable in the UK (although this is not so clear cut in terms of recommendations by representative bodies in some other countries) and the concept of “lateral trepanation” (removal of the third molar as a follicle) has passed into history. The decision to remove third molars depends on a balance between symptoms or pathology and relative risks in removing them (such as injury to inferior alveolar and/or lingual nerve, risk of fracture). If one third molar needs removing under a general anaesthetic it may be worth considering whether the opposite side should be removed at the same time. This is a balance of avoiding a second general anaesthetic in the future and the risks of complications in otherwise asymptomatic teeth. Table 1 summarises indications and contraindications for removal of third molar teeth.

Table 1 Indications and contraindications for removal of third molar teeth

| Indications | Contraindications |

|---|---|

| pain, specific to third molars (myofascial pain is not an indication) | patient refusal |

| pericoronitis / infection | active acute pericoronitis (although evidence disputing this exists) |

| advanced caries | asymptomatic |

| periodontal disease | high risk of injury to inferior dental nerve (relative contraindication) |

| periapical pathology | uncontrolled clotting disorder |

| disease of follicle, including cyst / tumour fractured tooth | |

| resorption of adjacent teeth | |

| as part of an orthodontic/orthognathic treatment plan | |

| mandibular angle fracture | |

| prophylactic removal in ‘at risk’ person (for example, bacterial endocarditis) | |

| as an aid to denture provision |

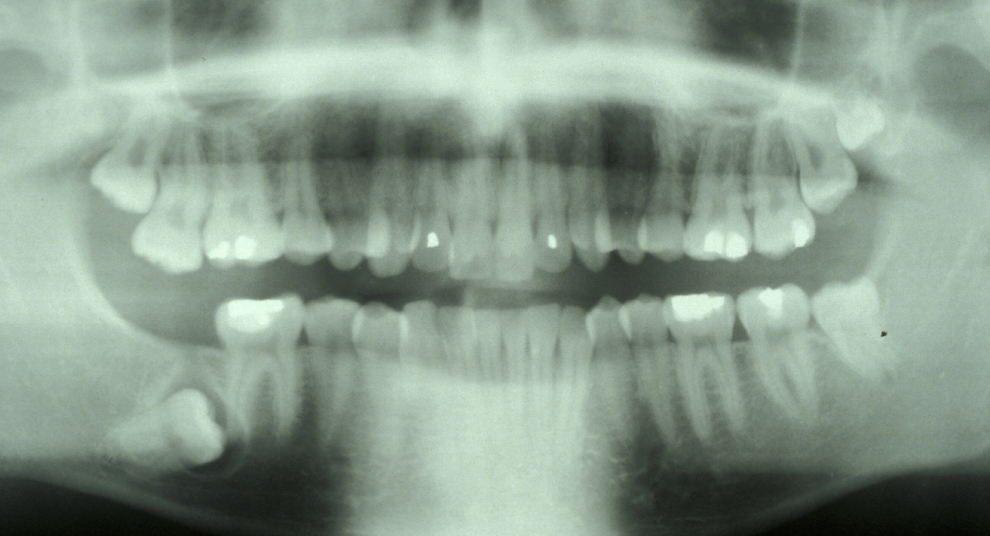

The commonest indication is recurrent pericoronitis. Pericoronitis is inflammation and infection of the mucosal flap (operculum) overlying a partially erupted tooth, usually the lower third molar (Figure 1). Pericoronitis may be acute or chronic.

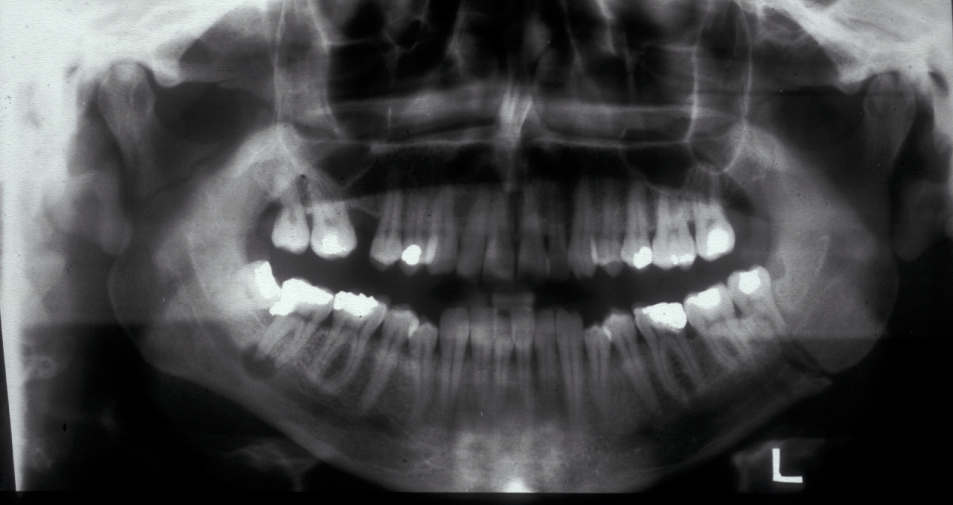

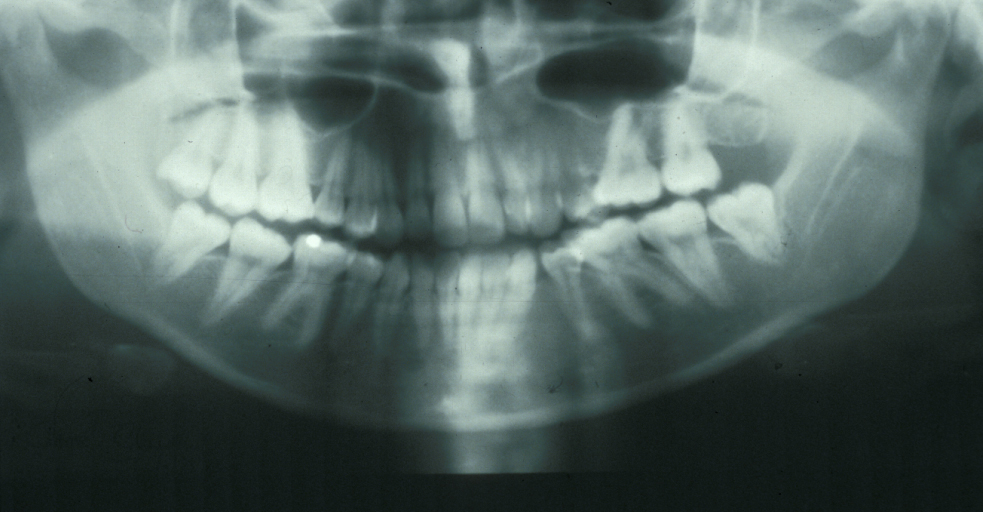

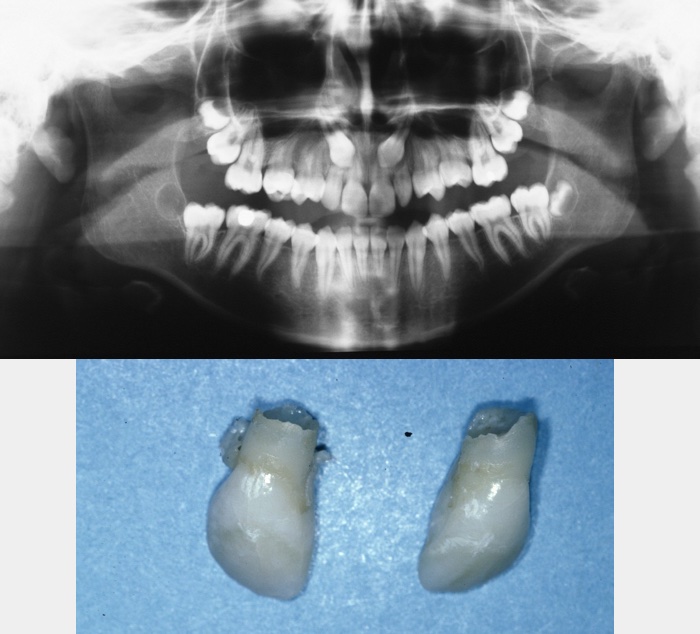

Figure 2 and Figure 3 illustrate examples of indications for removal of a third molar tooth.

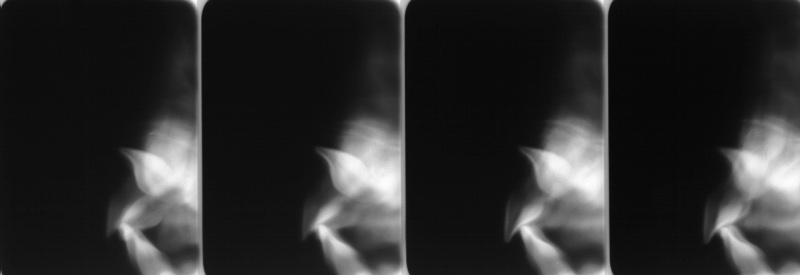

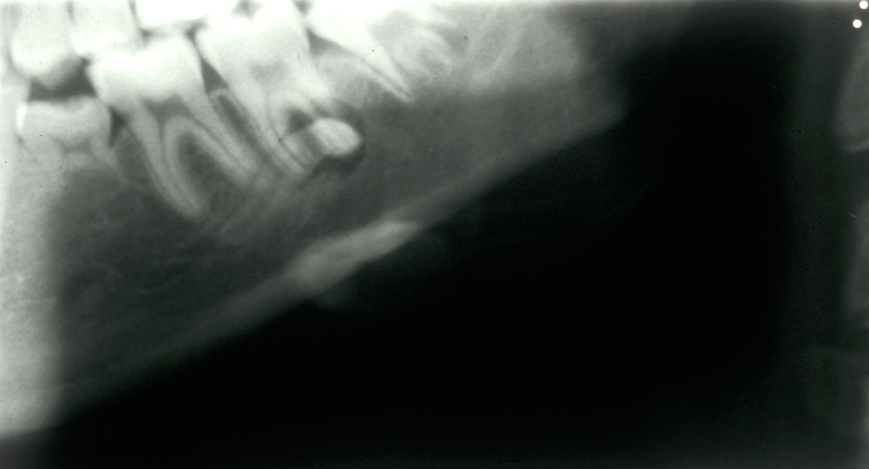

Assessment of the tooth is both clinical and radiographic. If somebody presents in pain, it is important to establish that this is coming from the third molar and not elsewhere. Pain is often vague, poorly localised and may be referred from another tooth, or as part of facial arthromyalgia (condition affecting the jaw joint). A dental panoramic radiograph is ideal as it helps to assess all the teeth at once. The health of the adjacent molars may influence the decision whether to remove the third molar or not. Large crowns or old restorations are all at risk of dislodgement during surgery. It is also worth considering whether alternative treatment options are available. For instance, pericoronitis due to an over-erupted upper third molar may be dealt with by extracting that tooth only, with or without operculectomy. In the presence of other teeth of poor prognosis, will it be better in the long term to save the third molar which may be used as a denture or bridge abutment in the future?

Having established that the wisdom tooth needs to be removed, other points in the assessment include:

- tooth position (vertical, mesioangular, distoangular, horizontal or across the arch).

- depth and degree of impaction;

- obstruction to eruption (what is the tooth impacted against?);

- root morphology (the curvature of the roots controls the path of withdrawal);

- relationship to the inferior dental nerve canal;

- associated pathology (for example, cysts);

- bone density;

- status of second molar tooth (in selected cases where this tooth has a poor prognosis it may be better to extract it and leave the third molar).

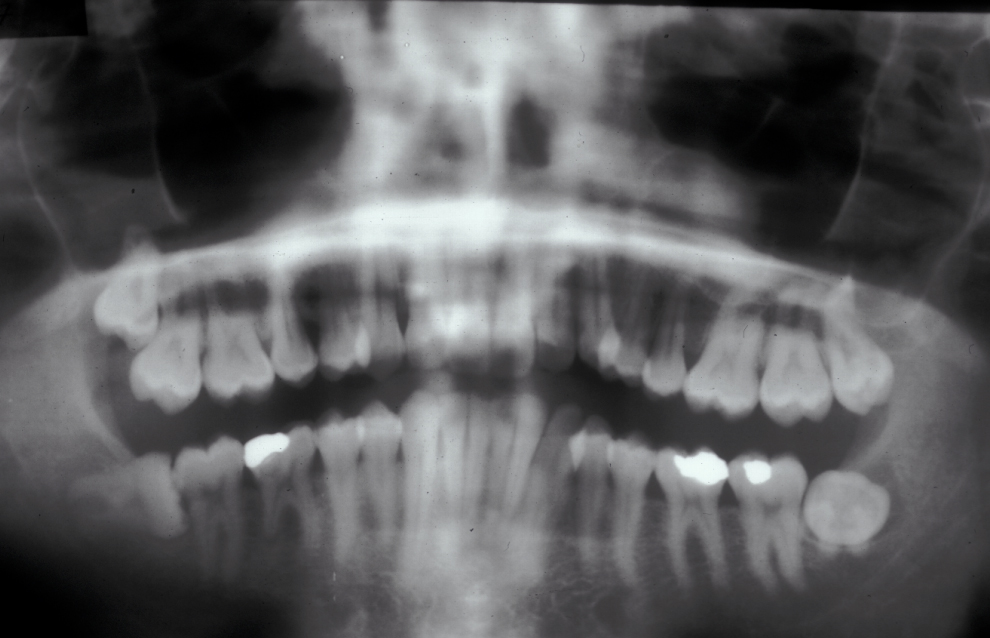

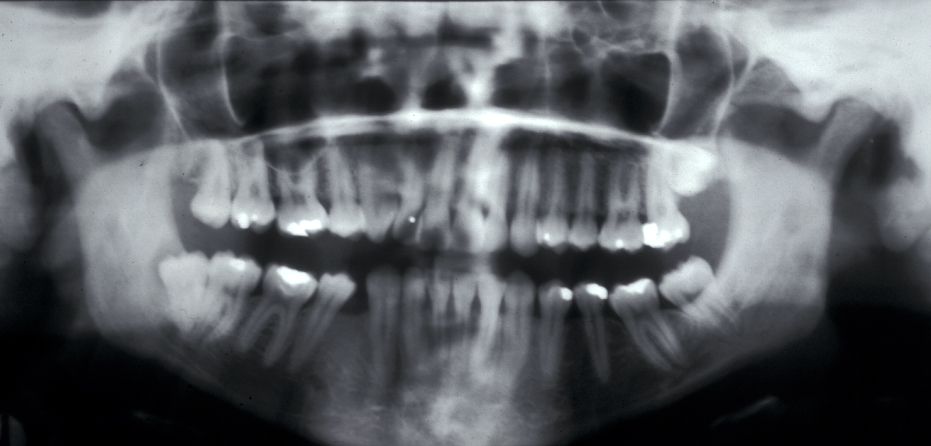

These points help to determine whether the tooth can be simply elevated or will need a surgical approach. A series of radiographs depicted in Figure 4 to Figure 8 illustrate these points further.

Canines

The incidence of impaction of the maxillary canine is between 0.9 and 2.2 %. It is twice as common in females as in males, and is much more common palatally (toward the palate) than buccally (toward the cheek). The incidence of impacted lower canines is low. Many aetiological factors have been cited including generalised systemic causes, crowding, prolonged retention or early loss of the deciduous canine, ectopic development of the tooth bud, presence of an alveolar cleft, ankyloses (joint or other bone fusion, including fusion of a tooth with bone), formation of cysts or neoplasms, or dilacerations of the root. Palatal impaction is known to be more common in individuals with diminutive or absent lateral incisors. This has led to the theory that the lateral incisor root is important to guide the canine into position, although this theory is unproven and perhaps simplistic. Impacted upper canines, both palatal and buccal, are often causes of lateral incisor resorption and this tends to be initiated relatively early before the age of 11 (Figure 9).

Permanent upper canines normally erupt around 11 to 12 years of age. If they cannot be palpated in the buccal sulcus by 9 to 10 years of age, then a thorough clinical and radiographic investigation should be undertaken to accurately locate them. If the canine is buccally placed it can usually be palpated and the lateral incisor may appear proclined, as its root has had to take up a relatively palatal position in order to accommodate the buccally placed root. If, however, the canine is palatally placed then the lateral root is usually in a normal position. A bulge may be palpable palatally, although this is often only present when the canine is relatively superficial in older patients. Radiographic investigations should be used in order to localise the canines and to assess the condition of the roots of adjacent teeth. In a significant proportion of cases some root resorption occurs, although this is rarely severe.

If ectopic canine development is identified at an early stage, interceptive treatment can be instigated in order to correct the canine’s eruptive path. This involves the removal of the deciduous predecessor and has a good success rate especially in less severe cases where there is no crowding.

Failure of incisor eruption

Failure of eruption of upper incisors is relatively rare and can occur for many reasons including previous trauma, root dilacerations (distorted shape; see Figure 10), presence of a supernumerary tooth, local failure of eruptive mechanisms, or the presence of pathology. If an upper central incisor is noted to be delayed in its eruption, then a thorough clinical and radiographic examination is warranted. This would be the case if it remains unerupted significantly after their expected time of eruption (at 6 to 7 years of age), if one incisor is unerupted over six months after its contra-lateral partner, or if it is unerupted after the eruption of the lateral incisors.

Clinical examination should note the status of the primary dentition, the position and angulation of adjacent teeth, and involve the palpation of the buccal sulcus and palatal vault. Primary radiographic investigation of the area should identify the reason for failure of eruption and an upper anterior occlusal is a useful view to do this. Radiographs should be examined for evidence of supernumerary teeth, root dilacerations, and to ensure an intact periodontal ligament. If failure of eruption is due to dilaceration of the root, orthodontic alignment will only be possible if the degree of dilaceration is not severe.

If failure of eruption is due to severe dilaceration, ankylosis or resorption (internal or external) then the only option is to extract the tooth. This should be undertaken in the same manner as for any unerupted tooth; accurate localization, adequate surgical exposure and careful removal. If the unerupted incisor(s) appear(s) of normal morphology with no obvious cause for their failure of eruption, then they should be exposed and given the opportunity to erupt.

Other ectopic teeth

The same principles used in the treatment of ectopic canines can be applied to other ectopic or impacted teeth. The underlying principle to consider is whether it is possible, desirable and necessary to align the tooth. If greater harm or little benefit will accrue, then it is probable that another course of action should be undertaken

Infraoccluded primary teeth

Infraocclusion (insufficient projection to reach normal occlusal plane) of primary teeth is relatively common and is caused by a focal area of ankylosis preventing normal eruption occurring during dentoalvelor development. It is often self-limiting with the tooth either re-erupting or being exfoliated prior to the eruption of its permanent successor.

Occasionally severe infraocclusion occurs. This is defined as when the marginal ridge of the primary tooth is below the level of the gingival margin. In these situations, the tooth should be extracted. These extractions are usually uneventful with the area of ankylosis not causing any significant problem. Occasionally, when the infraocclusion occurs early, the deciduous tooth totally submerges and not only prevents eruption of its successor but may cause adjacent teeth to tip towards the infraoccluded tooth, restrict development of the dentoalveolus (leading to lateral open bites), or, because of its continued communication with the oral cavity, may lead to decay, periodontal disease or periapical pathology. In these cases, it will be appropriate to remove the tooth and the technique employed will depend on accurate localization of the tooth by clinical and radiographic examination (Figure 11 and Figure 12).

Supernumerary teeth

Supernumerary teeth are relatively rare with an incidence of 1 to 3 % in the permanent dentition and 0.3 to 0.6 % in the primary dentition. The vast majority are located in the maxilla (90 to 98 %) with most of these found in the premaxilla.

Supernumerary teeth can be described by their morphology, being either rudimentary or supplemental. Supplemental supernumeraries tend to erupt and are then usually extracted to allow normal alignment of neighbouring teeth.

There are three types of rudimentary supernumeraries:

- conical – these have normal root development and can be inverted. They are usually positioned between the upper incisors but can become palatally placed as the rest of the dentition develops forwards and downwards;

- tuberculate – these are barrel-shaped teeth with little or no root formation:

- complex/compound odontomes (irregularly grown dental tissue).

The decision on whether treatment is required is dependent on the site of the supernumerary and whether they will affect the eruption or development of adjacent teeth. In order to localise the position of the supernumerary, X-ray images are required. This could be a panoramic radiograph in combination with a second plain film X-ray image to provide a second viewing angle, or a CBCT scan (Figure 13).

Conical supernumeraries often erupt and in these cases often have no effect on adjacent tooth eruption but may affect tooth position. They can also be a rare cause of a median diastema (gap between front teeth). If they erupt then they should be extracted. Inverted conical supernumeraries will not erupt and may, depending on their position, affect adjacent tooth development. If this is the case then they should be surgically extracted. Tuberculate supernumeraries often develop in the cingulum area (region at the base of the crown of the tooth) of the upper central incisors and are a common cause of the failure of upper incisors to erupt.

If a supernumerary is present and preventing tooth eruption it requires removal. The decision as to how and when to undertake treatment involves thorough assessment of the severity of the problem, general factors including somebody’s attitude to treatment, and what other treatment may be required. Both immediate and delayed removal of supernumerary teeth has been advocated.

Immediate or early intervention for all supernumerary teeth has the advantage that it prevents or minimises disturbance of the development of surrounding teeth. However, it does place adjacent teeth at risk of damage and may not be necessary as no problems may ensue. Delayed treatment ensures there is less risk of damage to adjacent teeth, a significant risk in younger patients with incomplete root formation.

The decision as to whether to undertake immediate or delayed treatment has therefore caused much debate. Conical supernumeraries should be left under observation unless they are causing developmental disturbance. Tuberculate and inverted conical supernumeraries should be removed immediately if this can be achieved with no harm to adjacent teeth. If, however, the upper central incisors have erupted, treatment should be delayed until after the eruption of the lateral incisors, as early treatment will not have any significant effect on tooth position.

Factors to consider in conjunction with orthodontic treatment planning

Orthodontic treatment is primarily concerned with the growth of the face, development of the dentition and the prevention and correction of malocclusion. As such, there is much that oral (and/or maxillofacial) surgeons and orthodontists can offer each other when treating patients, with very often a joint approach being necessary. Surgical techniques that may help the orthodontist include:

- removal of impacted or ectopic teeth (Figure 14);

- treatment of impacted supernumerary teeth;

- removal of infraoccluded primary teeth;

- exposure of unerupted teeth;

- tooth transplantation;

- single tooth osteotomy;

- orthognathic surgery .

The presence of a malocclusion as such does not indicate a need for treatment. Also, there are often many different treatment options and only by consideration of all factors can the most appropriate treatment be determined. These factors include:

- patient expectation, desire and co-operation;

- patient age;

- oral hygiene and diet;

- caries experience;

- teeth of poor prognosis;

- crowding;

- hypodontia (absence of one or more teeth) and microdontia (one or more teeth smaller than normal);

- other space requirements including levelling curves of Spee (curvature of the mandibular plane of occlusion), centreline correction, expansion or constriction of the arches (including overjet reduction).

In determining the most appropriate treatment when a combination of dentoalveolar surgery and orthodontics may be required, it is imperative that the patient and those undertaking both the surgery and orthodontics all have a full understanding of the aims of treatment. This is best achieved by undertaking a joint consultation where the risks and benefits of all options can be discussed and considered. While the age at which treatment starts seems to vary from country to country, there seem to be little differences in clinical practice.