Mental health

Nothing is more ‘normal’ than being anxious or stressed by receiving bad news (or having to deliver bad news), being in pain, being confronted with an unknown situation, feeling helpless and thoroughly not in control, having to make far-reaching and life-changing decisions, or having to adapt to new and different, lasting life situations and permanent dysfunction or disfigurement. Individually variable levels of stress and anxiety are a natural reaction to all of these situations. In fact, to a certain extent these mechanisms have a protective function in that they can help to cope with such challenges by providing a certain focus to deal with an issue. But, as the old wisdom goes: too much of a good thing can be bad.

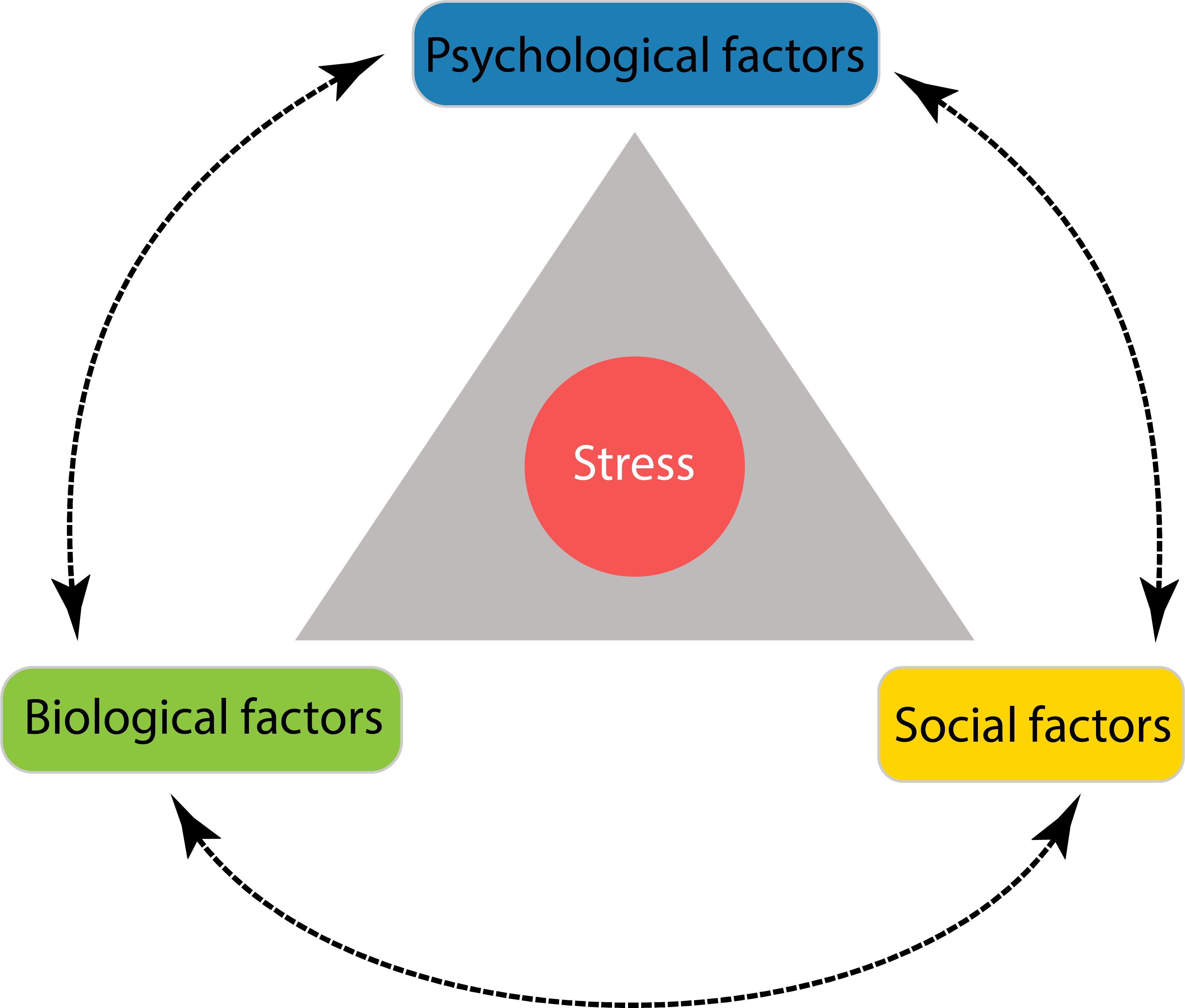

What amounts to a healthy and necessary stress / anxiety reaction is not only individually different, it is best seen on a spectrum and is composed of different contributing components. The multifactorial overlap of physical and mental health can be depicted in a triangular relationship (Figure 1).

This pictorial representation is in some bizarre sense a contradiction in itself. It looks crisp and clear and gives an overview of the main factors, being defined as biological, psychological and social, and their interconnectedness; and it places the individual at the centre. This pictorial summary implies simplicity, clarity, and separation of relations & reactions but nothing could be further from the truth. The best approach we can think of is to accept that we truly are all in it, all together engaged in some complex network of humans; patient, carers and clinicians. In turn, the best way we could think of discussing these matters is to provide a disorderly overview of known sources of stress and anxiety for different stakeholders at different stages of disease and treatment.

The main focus of our story is the overlap of physical and mental health in the context of maxillofacial conditions. However, the story does reflect many broader and general issues – maxillofacial conditions are merely a piece of the jigsaw puzzle commonly known as the human condition.

At the time of diagnosis / before treatment

At this stage, there are essentially three different sets of circumstances that give rise to, or are associated with mental health issues:

- underlying mental health conditions that present with physical symptoms;

- some relatively minor / common, benign condition in need of treatment;

- a serious diagnosis with life-changing outlook and urgent need to arrive at decisions regarding treatment options.

Some underlying mental health issues are known to lead to physical symptoms from the maxillofacial spectrum. Many of these physical symptoms broadly fall into the category of facial pain syndromes (often referred to as atypical or idiopathic pain), and after exclusion of underlying physical conditions, can be a symptom of depression (or some other, less common psychogenic causes). Anxiety is known to be associated with trismus and bruxism (grinding teeth) and related temporomandibular (jaw) joint problems. It may well be that a maxillofacial clinic appointment turns out to be a first step in tackling a mental health issue and leading to a referral to mental health services. Another situation in a maxillofacial clinic where a careful investigation into potential underlying mental health issues, motivations and expectations can arise when somebody complains about their facial appearance, seeking surgical correction(s). It is not uncommon that somebody managed to convince themselves that fixing a perceived (or even real) facial-appearance problem may be a magic fix for some other, completely unrelated problem. Body image is a highly subjective psychosocial matter.

Being apprehensive ahead of some minor intervention is surely a perfectly normal reaction when faced with an unfamiliar situation, especially when the situation involves having done something to one. It becomes more of a mental health issue when this turns into anxiety and fear, sometimes to the extent that people may forego necessary treatment and an initially minor problem escalates to a serious condition (an untreated dental abscess would be an example for such a situation). The fear of needles and claustrophobia are just two common examples of mental health issues negatively interfering with timely and necessary medical treatment. It is fair to say that most clinicians are well aware of anxiety issues and teams are well versed and skilled to help somebody through the process. It is a common outcome that, after the event, somebody will be quite overwhelmed by the observation that fear and anxiety were by far the worst part of the entire experience, much worse than any needles, interventions and so on. With a little bit of luck, therefore such an experience may even have some unintended positive side-effects by strengthening somebody’s confidence, resilience and willingness to trust others in future similar situations.

Being faced with a serious diagnosis, possibly of a life-changing or life-limiting condition, is an entirely different situation. Such situations in maxillofacial surgery include serious trauma, severe infections, head & neck malignancies and a few other benign conditions. In addition to the shock of diagnosis (even if not entirely unexpected), the situation presents with the need to make decisions about many unknowns and often involving lack of understanding of crucial background information. All of this taken together amounts to a highly stressful situation for patients and relatives/friends/carers alike.

Different people will have different coping strategies at this stage. A coping strategy is defined as the cognitive and behavioural effort & ability to deal with an essentially unresolvable problem. It is obvious that this has an impact on mental health and emotional wellbeing. The latter is a key aspect in lowering stress levels for all involved.

It has been found that the coping strategies of head & neck cancer patients at diagnosis are varied, with most people seeking social support, some resorting to rational operational modes (such as seeking out factual information), and only very few taking their stress out on others or following some cognitive escape/avoidance strategies. If anything, these findings indicate that clinicians should not make any global assumptions about resilience, compliance and engagement of this group of patients and their relations. It is known, however, that this patient group has higher than average depression rates before any diagnosis (in fact, some malignancies may release chemicals that can trigger depression). If unrecognised, this may lead to underreporting and undertreating mental health issues and result in a lack of compliance with physical treatment(s). It is an entirely different question which mental health / psychosocial interventions at this stage are most promising, appropriate and helpful.

Decision making about treatment options (where there are choices) for head & neck malignancies includes uncertain trade-offs about a range of immediate and late, often severe adverse effects, and sometimes about increased impairment or morbidity in exchange for higher survival chances. These are essentially impossible choices about unknowns to make, even if somebody is reasonably well informed. That in itself is a challenge for many, especially so because a state of emotional distress is for most people not the condition where clear and calm thinking is enabled. When asked about their priorities in decision making, at this stage patients and their relations seem to have similar priorities, with cure, survival time and absence of pain top of the agenda. There may be important decision-making effects at play here, when patients feel they should go along with the preferences of their nearest and dearest. Survival seems the paramount concern and overshadows all other aspects at this stage. Patients seem to be inclined to cope with short-term endurance of acute stress and treatment-related effects in the interest of long-term gain (where, at this stage, gain is seen as cure or extended survival). These reflections, ideas and opinions before treatment as reported in the literature are mostly derived from questionnaires and as such may have some bias and/or may especially underestimate pre-existing depression and anxiety and the corresponding clinical impact. Nevertheless, awareness of, and understanding about cognitive load and stress in the situation by all involved is crucial in enabling the best possible decisions to be made, and to cope and live well with the consequences of the decision. This is almost a trivial, everyday ‘wisdom’ about how to get on with ‘normal’ life, but it is obvious that in exceptionally stressful situations it is exceptionally difficult to exercise these life skills.

During treatment

It may appear slightly counterintuitive, but during treatment most patients faced with serious conditions are least stressed, whereas it is a period of high stress levels for their relations. This is broadly true for minor as well as for major conditions and interventions. In part, this pattern is explained by a well-oiled machinery that takes care of a patient and their needs in an all-encompassing way. For some, however, this condition of being taken care of is a source of distress because they feel they have lost control. This mechanism is similar to that causing stress for relations during that phase of feeling disempowered. A potential major source of stress and anxiety at this stage is lack of meaningful communication on offer from the clinical team. Patterns of mental health issues vary with length and type of treatment modalities for serious conditions. Having realistic expectations about recovery, timelines and outcomes from the start is helpful for most people – which brings us back to the importance of proper communication between all involved at all stages.

Specifically for people undergoing prolonged treatment schemes for head & neck cancer, there are a number of potent stress factors during that period of time, and as a result typically depression and anxiety occur together and reinforce each other. In fact, some have said that cancer treatment as such may be an under-recognised but reversible cause of severe mental illness. For example, a number of chemotherapy and immunotherapy drugs as well as corticosteroids are associated with depression as an adverse effect. Radiotherapy applied to the head & neck region may lead to hypothyroidism (underactivity of the thyroid gland) with low levels of thyroid hormones giving rise to depressive symptoms. In addition, many find that they have to deal with / endure acute toxicities such as pain, mucositis, dysphagia, xerostomia, tracheostomy, or enteral (tube) feeding. Looking back on it, many recall and describe this period in their life as an emotional rollercoaster, for themselves and their nearest and dearest.

After treatment, short- and long-term issues

It comes as a big surprise to many, patients and relations after major interventions such as in the treatment of head & neck malignancies or major trauma, that often the post-treatment phase is perceived as the most challenging in terms of mental health. After discharge is probably the time with the greatest need for support so that this step will not feel like falling off a cliff edge. For many this includes the need for long-term supportive care (especially after radiotherapy) with regard to lasting oral dysfunction.

If one thinks about the course of events, it makes perfect sense that prolonged periods of intense treatments basically delay the necessary cognitive adjustments of a serious diagnosis and the enormity of the following events until after the acute treatment phase. Only then reflection on the severity and significance of events kicks in, in parallel to the necessity to adjust to long-term changes and impairments, sometimes referred to as the ‘new normal’. It is at this point when depression and/or anxiety often emerge, not least if discharge amounts to a sudden cessation of regular support. The effect is similar to posttraumatic stress disorders following other traumatic events but it typically includes a distinct element of grief about the lost ‘old normal’.

Depression is not a marginal or rare event for head & neck cancer patients, estimates are around 30 to 50 % of patients experiencing at least one episode of significant depression. This needs to be clearly distinguished from low mood – who would not go through a period of such feelings when faced with having to adjust to a rather different ‘new normal’ – where transient low mood is a very normal and necessary reaction to the situation and an adaptation to it. The prevalence of depression and the suicide rate amongst head & neck cancer patients are higher than in groups of other cancer patients, presumably because of the exceptional and exhausting emotional and physical burden. It is thought that this burden is so high because of constant reminders of the trauma, including fear of recurrence, physical symptoms, lasting impairments and disfigurement.

A high rate of depression is significant in several regards. There is a correlation between depression/ anxiety and reported pain levels (depression may reduce the pain threshold and permanent stress may amplify pain perception; physiological dysregulation effects caused by acute and chronic stress are well documented). Clinical depression has a negative effect on outcomes and serious effects on quality of life: depression is associated with longer hospital episodes, self-neglect, shorter survival times, higher mortality and morbidity in general, more adverse effects and complications with therapy, reduced participation in treatment decisions, less social support, more decline in physical fitness, even drop-out from treatment. Poorer outcomes when clinical depression is a co-morbidity may have psychosocial as well as biological reasons. When chronic and severe stress interferes with the release of stress hormones, this leads to changes in neurobiology and to increased inflammation and is common in depressive disorders. Biochemical markers along these lines correlate with poor outcomes. Where clinical depression is manifest, not only is it necessary to address and manage this as a co-morbidity, there may also be need to break a vicious cycle with stress driving depression driving stress and so on.

It is not possible to collate a comprehensive picture of the various mental health issues afflicting maxillofacial patients, especially people after head & neck cancer treatment. But a number of studies note trends that, taken together, can provide something similar to an overall picture:

- there seem to be similar levels of depression and anxiety at diagnosis, and three, six and twelve months after treatment – a clear hint that identifying mental health issues early is hugely important to avoid undertreatment;

- stressors change over time: in the early phases, fear of recurrence, sore mouth, dental health and fatigue are the main concerns; later on the concerns shift to low mood and lasting dysfunctions;

- the most deplored later and/or lasting dysfunctions are dysphagia, xerostomia, lack of teeth, taste disturbances, speech impairment and tube feeding; problems with social activities and intimacy have a lower profile (in fact, intimacy and sexuality concerns often go unreported and undiscussed);

- depression is strongly correlated with post-treatment alcohol and nicotine abuse and poor outcomes (continuing to smoke after treatment halves the cure rate of head & neck malignancies);

- many report stress from financial burdens, despite a high rate of people returning to work within six months of treatment, no return to work is correlated with significantly worse quality of life compared with integration back in work;

- body image (appearance as well as function according to one’s own perception) is another psychosocial issue for head & neck cancer patients; this being a highly subjective concept, there is a common disconnection between patient / relation / clinician view and, therefore, need for honest and open communication;

- concerns about appearance tend to be correlated with physical impairments, giving a strong hint that joined-up physical and psychosocial rehabilitation is often the best way forward;

- depression is not more common when receiving end-of-life care than in non-palliative circumstances when somebody lives actively with / after malignancy;

- despite the many and often severe stress factors and documented difficulties experienced by head & neck cancer patients, many report reasonably good and stable quality of life, often very similar to pre-treatment quality of life about a year after the end of intense treatment – a testament to the amazing resourcefulness and coping strategies that many people have, or develop.

How about the clinicians?

All of the story so far has taken a rather conventional view by almost entirely concentrating on patients and carers/relations. This obviously omits important stakeholders from the overall view, the clinicians. Like their patients, they are humans with their own mental (and physical) health challenges. Similarly to patients, different clinicians will have different coping strategies. Similarly to patients, some clinicians will be good communicators, some will be not. Knowing about and understanding each other’s situation and challenges, both ways, is a useful way to cooperate much better in this uneven patient – clinician relationship.

Maxillofacial surgery is a profession with high levels of burn-out syndrome. Emotional resilience, the ability to bounce back from stress, and performance in surgery is another area where physical demands of a role and psychological well-being overlap. For example, emotional resilience prevents errors by improving cognitive performance. To that end, self-awareness in the profession is helpful. And similar to patients, professionals can also benefit from social support within their peer group. This varies from country to country and has changed radically as clinicians are increasingly seen as employees in hospital environments. Confident patients can help clinicians to avoid any completely out-of-touch and misguided self-management (‘god complex’). Self-awareness and critical reflection is important in order to strike the right balance between compassion and professional distance. To understand such behaviour patterns may be useful for patients to ‘read’ their clinicians: if patients remember that the clinician interacting with them is just another human being, with strengths and weaknesses, that will make for a more fruitful and balanced working relationship. Take for example, the medical language – this jargon of the profession actually functions both as a professional short-hand tool and as a protective agent for some clinicians to maintain an appropriate distance and to avoid to over-expose themselves to some of their patients’ problems. It is a little bit of a debated topic, though.

There are a number of unresolvable dilemmas: whilst a good clinician will be able to strike the right balance of empathy and professional distance, they may have a day when they had to deliver the same messages to ten people over the day, and by the time the eleventh person comes their way, their empathy resources are exhausted, even if they fully acknowledge that a routine situation in their professional day is anything but routine for the patient.

We can conclude here with a very short and very simple message to all stakeholders: communicate with each other as much, as honestly, and as well as is possible – it helps all and contributes significantly to the best possible outcomes, no matter what the nature of the condition is. With this message, we are now ready to look at the various interventions that may (or may not) help with mental health problems commonly encountered in maxillofacial surgery.