Benign lump

Contents

Benign lumps of the mouth, jaws and face

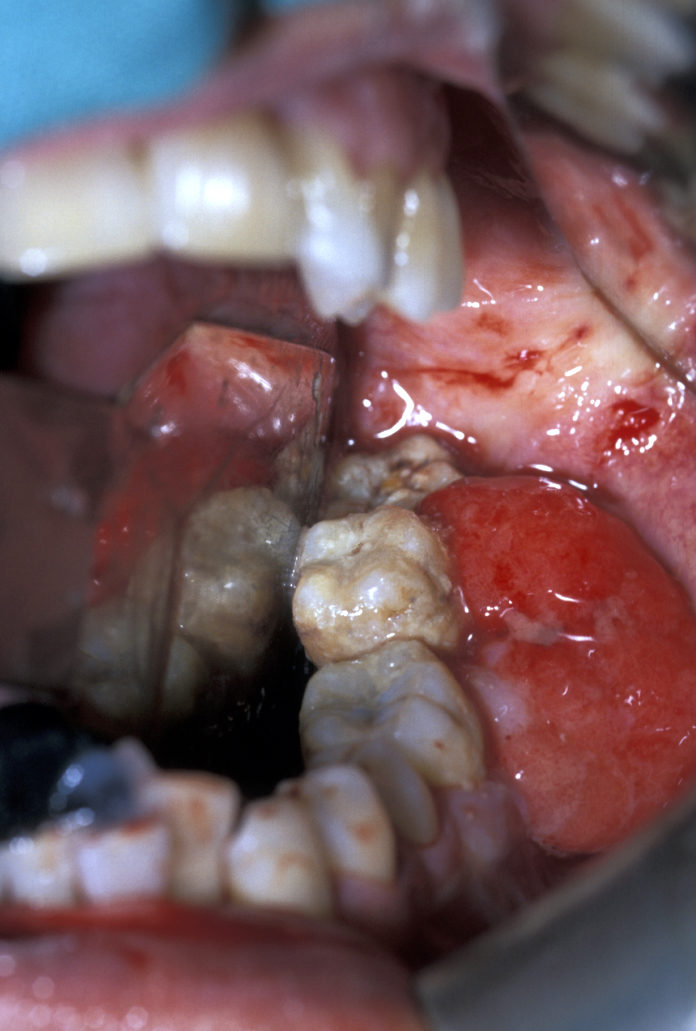

Brown tumour of hyperparathyroidism

This is a giant cell lesion which can look extremely florid (reddish) and mandates early biopsy for diagnosis. It occurs secondarily to hyperparathyroidism (overactivity of the parathyroid gland), but this diagnosis is usually made only after biopsy of the lump (either incisional or excisional) when the findings of giant cells in a fibrous stroma (scarred connective tissue) mandate an assessment of bone biochemistry and measuring parathyroid hormone levels (PTH blood test).

Congenital (present at birth) epulis

This is a sessile (immobile) or pedunculated (with an elongated stalk of tissue) nodule containing granular cells on histological examination. Present at birth, the lesion is usually excised only once the child is one year old unless it significantly interferes with normal function.

Epulis

This is any gingival (affecting the gums) lump that has nonspecific features.

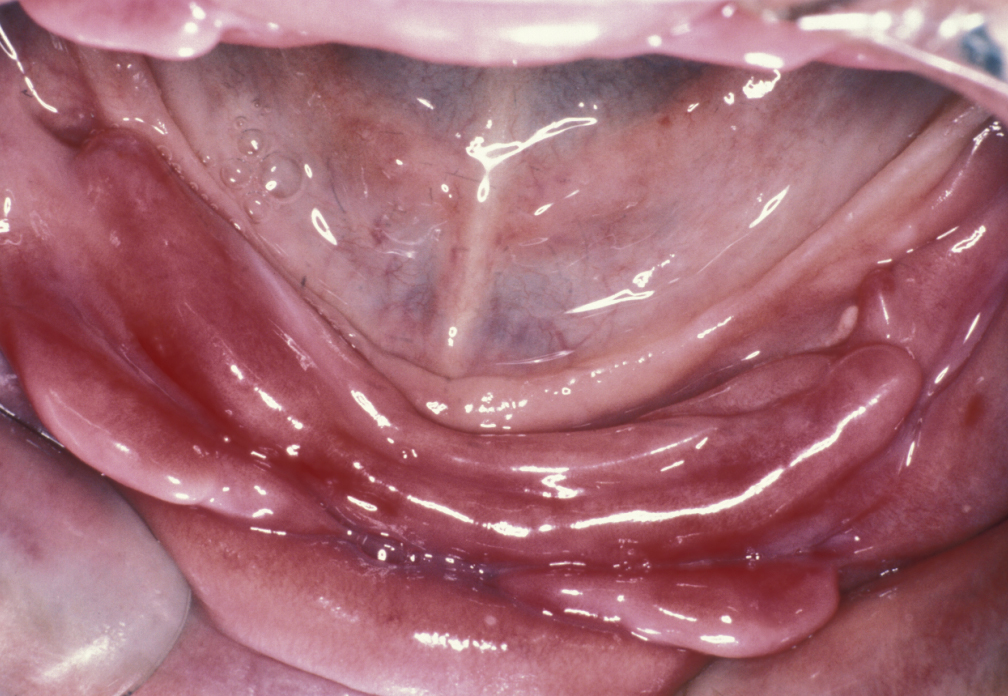

Fibroepithelial polyp

This is a benign but excessive response to low-grade recurrent trauma. These lesions may be sessile or pedunculated and can range from very small lumps looking like a genuine polyp in the cheek to lesions which can cover the entire palate (‘leaf fibroma’, see Figure 1).

Histology will show a very dense collagenous fibrous tissue lined by keratinized stratified squamous epithelium (layers of skin tissue cells).

Granuloma

Granulomata are swellings that show a characteristic histological appearance and may be caused by orofacial granulomatosis (see Figure 2 for an example), sarcoidosis, or implanted foreign bodies.

Orofacial granulomatosis is a persistent enlargement of the soft tissues of mouth, lips and the surrounding areas of the face. The swellings are not painful, the condition is thought to be of infectious origin. Sarcoidosis is a systemic inflammatory condition of unknown cause, it includes collections of granulomata and can occur in all parts of the body.

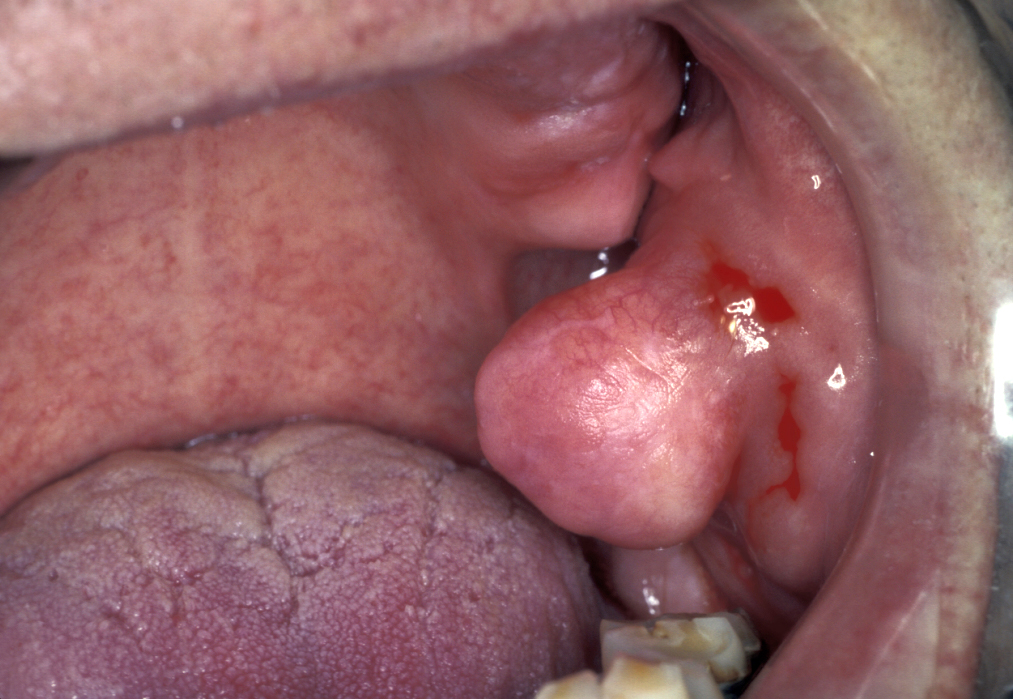

Giant cell granuloma (giant cell epulis)

This is a very vascular gingival swelling and is probably caused by chronic irritation (see Figure 3). Histological examination demonstrates multinucleate giant cells in a vascular stroma.

Gingival fibromatosis

This condition can be hereditary or, more often, drug induced. Phenytoin (anti-epileptic), ciclosporin A (immunosuppressive agent) and calcium channel blockers (common type of blood-pressure lowering agents) are the main causes. Figure 4 depicts an example.

Haemangioma

Haemangiomata are developmental lesions of blood vessels. They are usually congenital (present at birth) and tend to grow with the child. Most of these lesions (up to 80%) regress spontaneously. Haemangioma can be identified by blanching under pressure (classically by using a glass slide; see Figure 5). Haemangiomata are quite different from other vascular malformations (see below).

Hyperplasia

Particularly notable is irritation hyperplasia, which is a hyperplastic response to repeated trauma following denture-induced ulceration. Rolls of hyperplastic tissue which may be quite erythematous (red) and resemble malignant disease are seen particularly in the buccal sulci (see Figure 6). This condition is more common in the lower jaw than the upper. Histology is similar to the fibroepithelial polyp (see above).

Lipoma

Lipomata are benign tumours of fat cells found anywhere in the body including the mouth (see Figure 7).

Papilloma

Squamous cell papillomata are multiple papillated pink and white asymptomatic lumps; they look like and are very similar to warts in skin. These lesions should be readily identifiable as such (see Figure 8).

The main aetiological factor is the human papilloma virus (HPV), and there is an increase in people with sexually transmitted diseases. Most oral papillomata are of no real significance and are not related to oral infection with HPV-16 or HPV-18, which is a transient infection affecting up to 10% of the population (more common in males than females) and is cleared within a year. This virus type is, however, clearly associated with HPV driven oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma which has a much better prognosis in non-smokers. The relationship between virus type, transient infection and virally driven cancer in specific anatomical sites in the head and neck remains unclear but prevention of infection by vaccination, changing safe sex practices or some as yet unknown intervention to remove an identified cause of head and neck cancer is a vital area of further research.

Pyogenic granuloma

Pyogenic granuloma is an inflammatory response to chronic irritation. Lesions are found in a variety of intraoral sites dependant on aetiology. Puberty and pregnancy ‘epulides’ are hormonally sensitive examples. Figure 9 depicts an example.

Vascular malformations

These are divided into arterio-venous fistulae (abnormal connection between a vein and an artery), high flow venous malformations, and low flow venous malformations.

Benign lumps of the neck

Traditionally and for practical reasons, these lesions can be divided into those commonly presenting in children and those commonly presenting in adults. There are fundamental differences in the underlying pathology of neck lumps in the two groups.

Neck masses in children

Head and neck neoplasia is a very rare cause of neck swellings in children. In children, neck swellings are usually either congenital or inflammatory. These neck masses also include a variety of cysts and fistulae.

Cervical lymphadenopathy (enlargement of lymph nodes in the neck) - it is important to realise that children get cervical lymphadenopathy very easily indeed, and persisting cervical lymphadenopathy in children, unlike in adults, is more frequently due to transient reactive lymphadenopathy than anything else.

There are, however, specific infective and inflammatory conditions which will cause lymphadenitis. These include cat scratch fever which causes a generalised lymphadenopathy, but particularly cervical lymphadenopathy. Many other bacterial infections including dental infections cause cervical lymphadenitis. Of importance is mycobacterial lymphadenitis, usually caused by atypical mycobacteria.

Sternomastoid tumour - this is probably a combination of spasm and small haematoma within the fibres of the sternomastoid muscle (pair of muscles, close to the surface, running along both sides of the neck) that creates the physical appearance of a mass. This can result in torticollis (wry neck) which can itself result in asymmetrical development of the head and face (postural plagiocephaly; flat head).

Neck masses in adults

Unlike in children, the finding of soft tissue mass in the neck of an adult is more often indicative of serious pathology. These neck masses can be divided into congenital, acquired, infective and tumours. Lumps present for a long time are likely to be less of a cause for concern. Rapidly increasing painful lumps are more likely due to infection. Hard painless lumps need urgent investigation by a specialist. These neck masses also include a variety of cysts and fistulae.

Benign tumours of the neck - benign tumours of salivary gland origin are most common. Schwannoma (usually benign tumour of the tissue covering nerves), neurofibroma (another type of benign nerve sheath tumour) and malignant tumours such as neurosarcoma account for approximately 25% of primary neck tumours, and the paragangliomas (tumours that originate in nerve tissue or near certain nerves and structures of blood vessels; see below) account for approximately 15%. Miscellaneous lumps such as lipoma (see Figure 10) and rhabdomyoma (benign tumour of skeletal muscles) are comparatively rare in the neck.

Neurogenic tumours - these can arise from any of the major nerves of the neck and are either schwannomas (neurolemmoma) or neurofibromas; the commonest nerve of origin is the vagus nerve (one of the cranial nerves, also known as the pneumogastric nerve; part of the control of heart, lungs and digestive tract).

Neurofibromas may be part of von Recklinghausen’s neurofibromatosis or they may be solitary. If part of von Recklinghausen’s syndrome, they will be associated with multiple neurofibromas and café au lait spots over the skin. There may be association between neurofibromatosis and multiple neuroendocrine syndromes. Isolated neurofibromas can be excised although generally speaking the nerve will be irrevocably damaged by the excision and will require primary nerve repair.

Schwannomas on the other hand tend to stretch the surrounding nerve sheath and can often be excised while maintaining the integrity of the nerve of origin (see Figure 11 for an example).

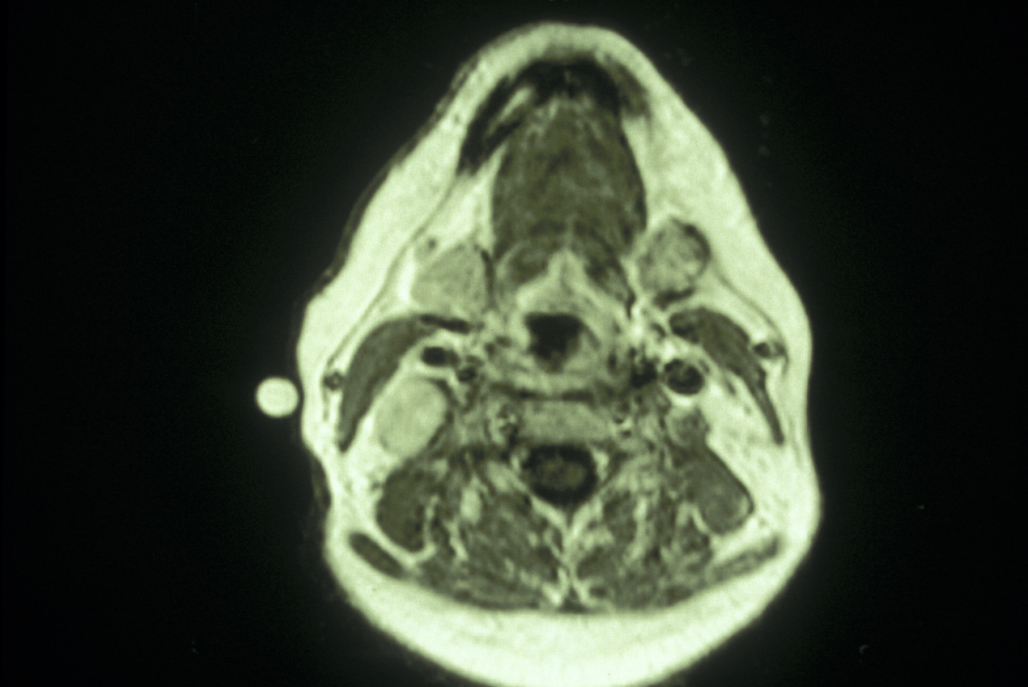

Paragangliomas - glomus vagale tumours are vagal paragangliomas arising from the mass of paraganglionic tissue within the perineurium of the vagus nerve just below the skull base. These may extend through the jugular foramen (aperture in the base of the skull). This is a slow growing mass in the upper neck, and symptoms are relatively late (pulsatile tinnitus, vertigo, deafness and pharyngeal pain). These tumours need to be investigated by MRI or CT scanning and should be excised because they are at the risk of spreading into the cranial cavity. These are extremely vascular tumours and as most of them are crossed by the internal carotid artery, there is a high level of risk of vascular injury.

Carotid body tumours - the carotid body tumour (glomus tumour) is the most common paraganglioma in the head and neck. These are uncommon tumours representing 0.6% of head and neck neoplasms and approximately 0.03% of all neoplasms. These tumours arise from the chemoreceptor bodies at the bifurcation of the carotid artery. Carotid body tumours can be distinguished on MRI or CT imaging from glomus vagule and glomus jugulare tumours (see below) because they tend to splay the internal and external carotid arteries, whereas the other two tend to displace the internal carotid artery anteriorly. There may be a clinical history of a slowly enlarging painless lump in the middle of the neck, this may be pulsatile. The lump will feel firm and rubbery, and it is classically described as being mobile from side to side, but not up and down (although this is not a particularly useful clinical sign in reality). The higher prevalence of carotid body tumours has been related to chronic hypoxemia from COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) and high altitudes. The sporadic form of carotid body paraganglioma is more common than the inherited variety and tends to occur more often in women. Familial tumours account for about 10% of all carotid body tumours and have an autosomal dominant mode with variable penetrance and higher incidence of bilateral tumours (which needs to be excluded with ultrasound scanning).

Carotid body tumours are extremely vascular tumours and hence biopsies should not be attempted. These tumours are characteristic on CT and MRI scans or by MRA (magnetic resonance angiography). These techniques may demonstrate widening (classic contrast and angiographic finding) of the carotid bifurcation (Lyre Sign). The majority of these tumours are benign although it is impossible to distinguish benign and malignant carotid body tumours on the basis of histology alone. Occasionally the tumour may transmit the carotid pulse or demonstrate a bruit or thrill. Because of its proximity to the carotid vessels and the X-XII cranial nerves, enlargement of the tumour may cause progressive neurological symptoms such as dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), odynophagia (distorted sense of smell) or hoarseness. There may be a history of symptoms suggestive of excessive catecholamine production (blood test for vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) levels; VMA is a metabolite of catecholamine) such as fluctuating hypertension, flushing and palpitations, but this is actually very rare.

Glomus jugulare / glomus tympanum - these paragangliomas arise around the jugular ganglion (part of the vagus nerve near the base of the skull) and tend to present with deafness and cranial nerve palsies. They rarely present as neck lumps.

Infective neck masses - these tend to be either manifestations of cervical lymphadenopathy (enlargement of lymph nodes) or abscesses of the cervical fascial spaces.

Laryngocele - laryngoceles (abnormal air sac) arise within the circle of the laryngeal ventricle. They are commoner in males than in females and usually occur in people in their 60s. Most are unilateral, and 1% will contain malignant disease. Clinical findings include neck lump, hoarseness, sore throat, sometimes stridor (high-pitched breathing sound) and in 10% of cases there will be infection of the laryngocele.

Pharyngeal pouch - this is a diverticulum (Zenker’s diverticulum; a pouch) of the pharyngeal mucosa, usually of the median posterior wall passing through Killian’s dehiscence (a small area of the wall of the pharynx). Commoner in males than females and usually a condition found in people more than 70 years old. Mostly causing difficulty in swallowing, although halitosis (bad breath) and regurgitation of undigested food can also occur. There may be cough, recurrent chest infection, hoarseness or a neck mass. This requires a ‘barium swallow’ (X-ray investigation of the swallowing process) and pharyngeal oesophagoscopy.