Practical tips

Contents

The range of oral and maxillofacial conditions is wide and varied, the resulting range of difficulties encountered with oral food & drink intake is equally wide and varied. However, eating and drinking is important for everybody, way beyond the mere necessities of providing nutrition for the body. An old German proverb reflects this: ‘Essen und trinken hält Leib und Seele zusammen‘ (eating and drinking keeps body and soul together).

There will be times and circumstances where oral food intake is not possible and alternative feeding methods have to be used but fortunately, despite sometimes serious and long-term difficulties, almost everybody will be able to enjoy food and drink in some shape or form. The possibilities to adapt food and drink to accommodate various needs are endless (but more serious in-depth research into such matters would also be useful).

Other pages in this section are dedicated to taste, texture and temperature of food, a collection of recipes and cooking video demonstrations, lubrication of foods, the role of saliva in eating, the normal process of swallowing, some general patterns for adapting food textures and some considerations of nutritional needs.

Below we share a colourful mix of practical tips and considerations, many discovered (and tested) by the experts by experience – patients and carers. The collection is of the ‘pick & mix’ variety: choose and try what you feel is most useful for your situation. What works best is individually very different and will probably change over time, but there are some general trends. One general fact certainly is that maintaining the best possible oral hygiene greatly helps to support and enjoy eating. For example, if you only eat very soft or liquid meals your tongue will not self-clean as it normally would by processing hard foods and this will reduce your taste acuity (unless you take appropriate oral-hygiene action).

It may seem counterintuitive to have such a collection of practical tips around eating and drinking, and a cookbook and recipes for times when eating is difficult. It makes sense because preparing your own food (or even better: having somebody help you with it) gives you by far the best options to get your food exactly right for your needs and appetite, no matter how unconventional that may be at the time. Keep on trying to eat (unless you have been advised by your medical team not to take oral food for the time being), even if it is difficult and you can only manage small amounts at a time. It will help you greatly to return to some form of new normal and to more normal eating patterns later on. It will also help you to retain (or regain) your sense of taste and / or the mechanics of swallowing – by keeping it all in use and in ‘training’ (the body is a very efficient machinery – whatever doesn’t get used will be reduced or shut down).

In the kitchen / pantry

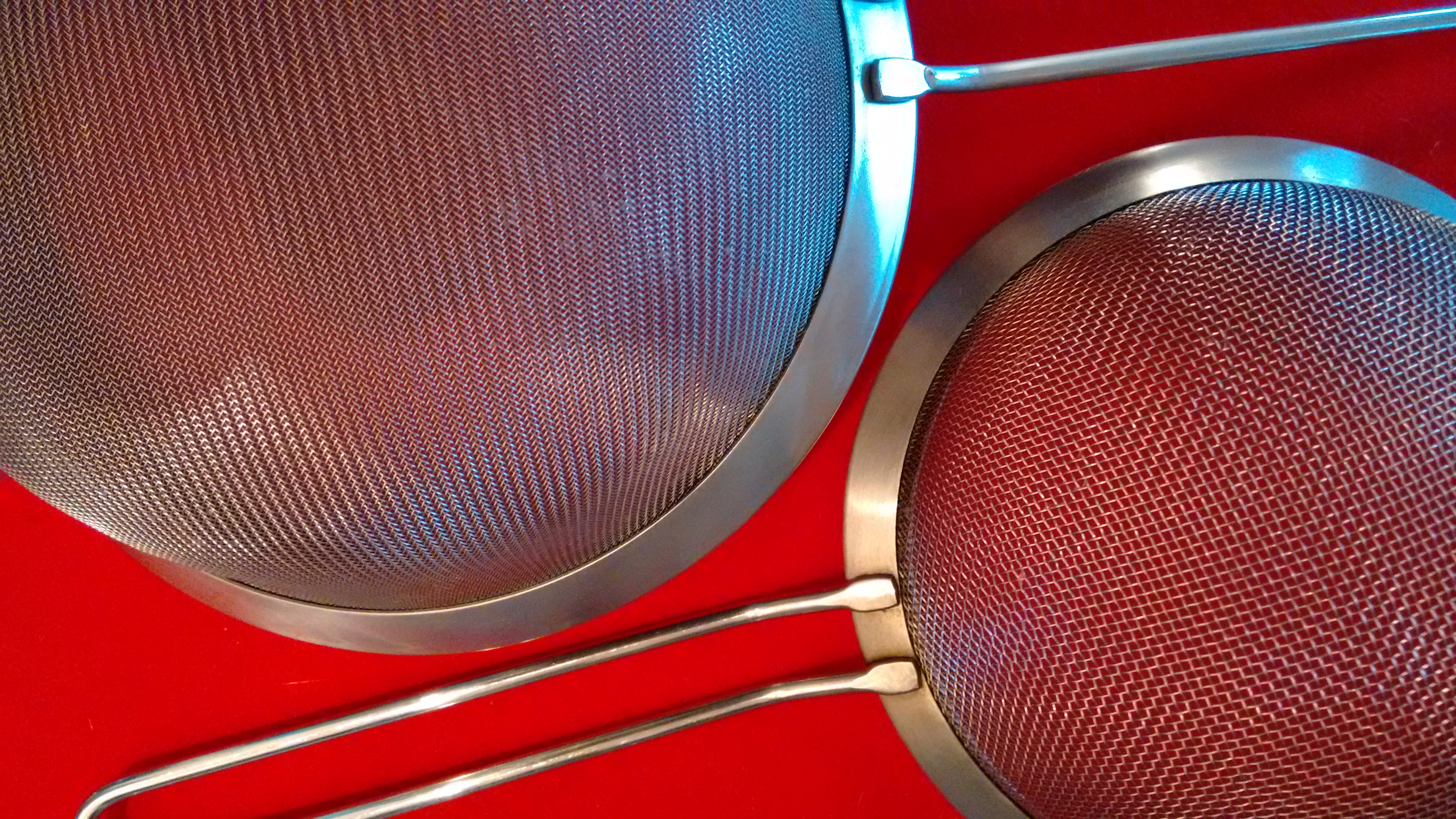

Nothing unusual is needed as far as kitchen gadgets are concerned: a reasonably powerful blender or food processor and a couple of fine-meshed sieves is all that is needed. What qualifies as a sufficiently fine-meshed sieve, again varies (see Figure 1): for most people a typical standard sieve as available from supermarkets will be adequate (Figure 1 right) to achieve a sufficiently smooth consistency of foods. If the slightest little ‘bit’ in your food bothers you, you will need to get a more finely meshed sieve from a more specialised kitchen shop or online supplier (Figure 1 left).

Clever combined use of fridge, freezer and microwave is useful to have an appetising selection of foods (almost) ready at all times. As soon as you start preparing food from scratch, there will always be some surplus - keep it and freeze it. Smooth purees are a great space-saving, freezable starting material for many different preparations, from liquid foods to jellies or purees. It will only take a few days of cooking from scratch and you will have a nice selection of nearly-ready meals in your freezer.

Fine oat meal and all kinds of tinned or frozen pulses (including chick peas, peas, butter and other beans, split red and yellow lentils) are convenient versatile cupboard bases for satisfying liquid and soft / smooth meals that keep the hunger away for a while (and are good sources of proteins too). Make sure that foods based on pulses are carefully pureed and the puree / liquid is passed through a fine-meshed sieve before serving. Because of their high content of purines, lentils as a major diet component can be problematic for people suffering from gout.

A visit to the baby-food aisle in your local supermarket may be a worthwhile excursion: if ordinary fruit juices or fruit purees are too acidic for you, try pear or apple juice or fruit purees for babies. These products are much less acidic and may just work for you. Generally, if fruit purees are too acidic, try mixing them with some Greek yogurt or whipped or double cream. That might be enough to remove the sharp edge (adding loads of sugar does not work). In order to boost your protein intake, you can mix / smuggle baby meals (chicken, for example) into smooth vegetable soups when heating your soup. Baby meals are best ‘hidden’ in other foods, their distinct lack of taste is not particularly attractive to most adults. Instant baby porridge could be a lazy breakfast option; it is perfectly smooth and designed to be easy to swallow (because babies need to learn to swallow safely, and you may feel young at heart…) but be aware that (sadly) these preparations tend to have a high sugar content.

If you want to avoid hidden sugar in your meals, do not use low-fat products (these all have added sugar, sometimes large amounts) and stay away from ready meals. Some preservatives in processed foods also can be difficult if you have problems with acidic foods. Many food preservatives are, chemically speaking, acids.

The two most familiar household ingredients for modifying the consistency and texture of foods are probably corn flour and gelatin (so called vegetarian gelatin is also available). These two texture modifying agents have different roles in the optimisation of food preparations.

If your meals are mainly based on liquids you may find that ever so slightly thickening the liquids can make eating easier, or your meal may feel more satisfying in that way. That needs a little bit of experimentation and corn flour or arrow root (mixed with a little bit of water, added to the gently boiling liquid food) may be the perfect thickener to adjust the thickness precisely as you want it. You need to try if this gives your liquid food a texture that is comfortable to eat at the most suitable temperature. In addition, corn flour or arrow root are useful for thickening the liquid component of mixed-texture foods to achieve a more homogenous consistency that is easier and safer for some to swallow (for example, fruit compotes). Please note that corn flour and arrow root are not suitable as thickeners when you suffer from dry mouth (see below).

The role of gelatin is slightly different. With the help of gelatin you can turn all liquids or thin purees into slippery jellies (sweet as well as savoury) which are particularly easy to eat. Sometimes a (cold) jelly can be easier to eat than the corresponding (warm) liquid, sometimes it may be the other way around. The gelatin slippery approach works well for liquefied fruit and vegetable purees, pureed meats, broth and juices which can all be turned into jellies. Jellies are very useful to maintain good levels of hydration if swallowing liquids is problematic – jellies are liquids in disguise. Again, it is all about your personal preferences but varying the thickness and degree of ‘slipperiness’ of your jellies will give you quite a diverse range of food textures; useful to battle any onset of food boredom.

Ordinary gelatin (which is made from animal collagen) has a special role in dysphagia (see below) diets: jellies made with ordinary gelatin are particularly slippery and easy to swallow because their melting point is close to body temperature. Vegetarian gelling agents produce more brittle, less slippery jellies (and mousses) with higher melting points and a different mouth feel. The otherwise extremely useful properties of jellies made with ordinary gelatin explain the following words of caution. If it takes you a considerable amount of time to get ready to swallow a portion of jelly, be aware that i) over the period of time the jelly may melt in your mouth and you may have liquid in your mouth, and ii) if you have normal saliva production, over time one of the enzymes in saliva, amylase, may break down parts of the jelly and again you may have liquid in your mouth( there are amylase-resistant thickeners available, if necessary).

Before we start with cooking: the good news is that there are really no restrictions as to flavours – almost everything and anything can be prepared in liquid, smooth or soft form at different temperatures. The only compromise is texture and that is quite straightforward to adjust according to what you feel is most comfortable and it usually does not involve a great deal of kitchen chores. Thinking a little bit outside the box and being imaginative and adventurous certainly helps.

At the dinner table

Serving food

Serve your food in small(ish) portions on/in small(ish) dishes – much less daunting when eating is hard work. Try to eat often and in small portions if you find eating is hard work. It helps if your food looks pretty and is nicely presented. Some / most people prefer social eating / company at the dinner table. Some prefer eating on their own, for example when conversation over dinner would be a distraction from paying attention to special swallowing manoeuvres. Please do NOT avoid company for dinner just because you think that your current table manners aren’t up to scratch. It doesn’t matter.

Cutlery and other tools

If you suffer from restricted mouth opening or have problems with motor control of the lip region, using cutlery, in particular big spoons is not exactly the easiest way to eat. Little flat plastic ice cream spoons work rather well if you can manage smooth and pureed, or other soft, foods. If you still prefer eating with conventional cutlery, have a look around for children’s cutlery with fairly flat and small spoons. Several people recommend using long-handled teaspoons (‘latte’ spoons). If metal cutlery feels uncomfortable (or seems to taste strange), replace it by plastic cutlery. Figure 2 shows a selection of cutlery and similar tools.

If your fingers turn out to be the best tool for the time being, there is nothing wrong with that! So much about standard table manners and etiquette is based on local culture and traditions. Most of the Middle East and Asia consider our western ways of eating with metal cutlery as fairly barbaric, for example, and in these parts of the world there is a refined etiquette about eating with your fingers.

If you can manage small pieces of soft foods once they have found their way into your mouth, you may want to try chop sticks; this also avoids inconvenient mouth gymnastics.

For liquid food, most people find the good old mug or a cup the most versatile dish to handle (somehow; it tends to be easier if the cup or mug is thin-walled). Using a paper cup and squeezing its lip into a V-shaped spout can give you a more targeted way to deliver liquids to your mouth. Alternatively, a baby cup with a spout may be convenient if you have no problems closing your lips around it. A large syringe is yet another way of delivering liquids into your mouth. If the mechanics of swallowing liquids is a problem (in particular with liquids occasionally ending up in the wrong pipe, for example when not paying attention, or talking while eating). Using a drinking straw can help in some cases, at least it is worth a try.

Dry mouth, xerostomia

If you are affected by a dry mouth you may find it easiest to eat cold, or lukewarm, liquid or nearly liquid, and smooth / soft foods. Go easy with salt and sugar (see below), both can make eating more unpleasant.

Smaller than normal amounts of saliva not only make eating more difficult and less pleasant because of reduced taste sensation, the lack of protection by saliva also makes teeth much more vulnerable to dental decay. Sugar in particular should be avoided: plaque bacteria, causing dental decay, thrive on a sugary diet. If manageable, sugar-free chewing gum can be useful. Not only will the chewing motions encourage saliva production, but xylitol (artificial sweetener in many chewing gums; other than normal sugar it is not converted to acids in the mouth) is harmful to the metabolism of plaque bacteria. Avoid acidic and sugary drinks, instead consider tea and green tea: both brews contain fluoride ions and thus can contribute to dental health. Watch out for foods with hidden sugar (the classic example being ‘natural fat-free yogurt’ – naturally, yogurt does contain a certain amount of fat, and there is sugar added to all fat-free yogurts).

Sometimes it is recommended to people with dry-mouth problems to sip water all the time to keep the mouth moist. That is most likely not a good recommendation. The main effect that this will have is that any remaining, small but important amounts of saliva will be diluted and/or washed away. It is a good idea to carry a bottle of water around to have some drink at hand when needed. But apart from that, there are other tried and tested ways to reduce the drying out of mucosa and tongue. For some people some of the commercial artificial saliva products help between meals and at night. But most people prefer certain foods as mouth-moisturising agents. Favourites include regular sips of buttermilk, broth, lukewarm salt solutions, sage infusions, cream or mascarpone, or good quality (non-acidic) oils.

It is not uncommon that it is recommended that people with dry-mouth problems essentially wash their food down with large amounts of water. That is not a good idea! While it is obvious that something needs to be done to help with swallowing, it is equally obvious that washing each small bite of food down with large amounts of water is counterproductive.

This is because i) it will make you feel full very quickly and you will not eat enough in that way; ii) it makes eating very unpleasant because large amounts of water do not contribute to a consistency of the food bolus that would trigger the swallowing reflex and thus requires a major forced effort to get anything down.

Using plenty of lubrication and suitable sauces of all kinds is a much better approach. Lubrication does not dilute your food further but will help to modify the consistency such that it is easier to swallow. One can explain well why gelatin-based jellies and custards are again and again reported to be very good lubricating agents – both can essentially mimic certain lubricating properties of saliva. Apart from these two special, universal lubricants, it depends on the chemistry and rheology of a particular food what will make a suitable lubricant.

The range of potential lubricants ranges from 100 % water all the way to 100 % fat, such as in oils and melted butter. Somewhere between these two extremes are milk, cream, chicken stock, gravy, mayonnaise. Most foods are hydrocolloids, complicated mixtures of fat, water and other components. Accordingly, it is to be expected that different types of food will be well, or not so well, lubricated by particular types of lubricants where the main difference between lubricants will be their different characteristic water-to-fat ratios.

Examples of useful lubricants are rich concentrated chicken stock (particularly nice with vegetables; make a large quantity, freeze in small portions in an ice cube container and use as you go), double cream or whipped cream, good quality rapeseed or olive oil (which will also go nicely with some sweet foods; some may find a hint of acidity of olive oil irritating), other oils (walnut, pumpkin-seed or grape-seed oils are really nice but are a bit pricey), any variety of smooth rich gravy (home-made, not from granules), good quality mayonnaise (preferably homemade; easy, see our recipes), mascarpone (rich Italian cream cheese) thinned with single cream, melted butter. All kinds of sweet and savoury custards and jellies - see our recipes.

There is no need to worry about these supposedly guilty pleasures. When you find eating hard work, and/or you are on a diet of liquid or pureed foods these foods are by necessity diluted. In addition, you will probably eat a little less than you normally would. In these circumstances these not-so-guilty lubricating pleasures are very welcome because they add nutrition, calories and proteins, to your diet without causing extra-efforts with eating.

Munching on pieces of fresh pineapple, or mashed pineapple, can help to make sticky saliva less viscous. Humidifiers help to improve the humidity of the room air, especially during heating periods. Some people report that using the smell of essential oils acts like a mouth-watering appetiser when used before eating, improving saliva production. Careful and regular oral hygiene is very important to avoid dental decay and gum inflammations.

Sore mouth

If your main problem is soreness of mouth and throat, creamy liquid and jellied foods are easiest to handle. Avoid acidic foods and choose dairy-based meals with little seasoning. Cold (or frozen) food is likely to be easiest to handle. Especially if you have sores or ulcers in the mouth it is a good idea to avoid sugar; this helps to prevent oral infections.

If you are affected by mucous and find that dairy products aggravate your problem, reduce the amount of dairy component in recipes and increase the amount of stock or water accordingly. Rinsing your mouth right after eating also helps.

Difficulty opening mouth, trismus

Fortunately, for many people variable levels of trismus are a temporary nuisance, a symptom of some acute condition or a temporary consequence / discomfort following some surgical intervention.

Unfortunately, severe and lasting forms of trismus can be a long-term problem after radiotherapy in the head and neck region, or a symptom of some other serious conditions. Severe forms of trismus present a challenge for the provision of a balanced oral diet – but equipped with some willingness to think outside the box and exploit whichever tricks there are to get tasty food into the mouth and safely swallowed: it can be done! It can even be done with a varied and interesting diet!

There are a few obvious starting points for a viable balanced diet for people suffering from severe trismus. Clearly, it will have to be mainly liquid foods and/or thin purees. That requirement in itself is not so much a restriction of foods (almost all foods can be pureed or liquified), the main problem is that liquids and thin purees are quite dilute foods and it may be a challenge to eat enough over the day. Therefore, it is helpful to use nourishing diluting liquids rather than water to adjust thickness of foods (anything, from cream or milk to non-dairy ‘milks’ to chicken or beef stock, etc).

It is a good idea to plan for plenty of time for eating and not rushing it. Over time, many trismus sufferers develop ingenious methods and tricks to adapt their favourite foods. Most become experts at slurping foods (practice makes perfect…), and that then may well include very soft small chunks of food that do not require chewing (think of tiny pasta shapes, for example, combined with completely smooth, no-bits versions of lubricating pasta sauces). It is generally recommended that foods should be free of ‘bits’ and the amount of sugary foods should be minimal because oral hygiene can be a challenge too with severe levels of trismus.

Difficulty swallowing, dysphagia

Swallowing problems are as widely varied as the underlying causes. Different conditions and problems will call for different solutions for optimal adaption of oral food; the speech and language therapists help to assess and monitor the oral food intake options and suggest the most suitable food textures.

It is important to assess and re-assess dysphagia problems over time because not all such swallowing problems have clear and obvious symptoms, but can lead to serious health consequences such as pneumonia caused by repeated aspiration of foods into the airway.

Despite the wide range of different swallowing problems, all calling for tailored approaches with the most suitable - and widely different - food preparations for different conditions, there are some general patterns and common aspects:

- the most comfortable volume of food which is easiest to swallow, seems to be around 5 ml, approximately equivalent to a heaped teaspoon portion

- avoid extreme mixtures of textures and consistencies of foods – these are the most challenging swallowing tasks if you have to process, for example a liquid and some solid food simultaneously (the classic example is chicken soup, broth with pieces of meat and vegetables). No need to despair if you really have an appetite for chicken soup – just separate the components and do not mix them in your mouth but eat them separately)

- if you need to swallow pills regularly, trying to wash pills down with water is another version of the chicken-soup problem. Instead, try to use slightly less liquid foods to get the pills down. Yogurt, apple sauce or other soft purees all work well and are much safer to swallow together with a pill. You may consider wrapping your pills in some other slippery foods such as liver paté, or butter / margarine to help with swallowing (a trick well known to pet cat & dog owners…). Please do remember that not all pills are suitable for crushing or grinding; if it is too difficult to swallow your regular medication(s) in the form of tablets or capsules, there may be alternative, more convenient delivery vehicles for your medication.

Texture is not the only aspect that can make all the difference between being able to eat something comfortably, or not. The temperature of your food also makes a huge difference. Many people with a variety of swallowing problems find that the colder the food the easier it will be to swallow (that is the reason why we have a number of unusual recipes for frozen foods in our recipe collection). Some people find that they can happily enjoy some foods in the form of ice cream (including savoury foods) while the same food in its ordinary warm form is beyond reach or not nearly as enjoyable. It is a good idea to experiment a little with food temperatures within your comfort zone of food textures. You may even discover that this texture comfort zone varies slightly as a function of temperature.

Temperature contrast can also work in your favour. For example, if you take a sip of carrot soup at ‘normal’ soup temperature followed by a mouthful of basil ice cream (see our recipe collection) and so on, the temperature contrast may well be able to contribute to a less cumbersome dining experience. The temperature contrast may enhance muscle tone and thus help with swallowing. There are no fixed or golden rules but a little bit of experimentation around the temperature of your food is definitely a good idea. Most foods taste good over a wide range of temperatures.

There are several surprisingly disappointing candidates as far as pureed food is concerned:

- long-grain rice fails miserably, it stubbornly retains a sharp crumbly consistency. Short-grain rice when well-cooked is slightly more suitable, alternatively rice can be replaced by rice flour

- pasta does not really lend itself to blending, it ends up as a rather unpalatable rubbery lump (try some of the really tiny pasta shapes instead, such as ‘stellette’ = little stars, or alphabet pasta)

- soft white bread can be troublesome because it tends to be sticky (rye bread (possibly crust removed) from a proper bakery is much less sticky)

- mashed potatoes are sticky because of the relatively large amount of starch in potatoes and tend to be difficult to swallow. That can be overcome by using lots of lubrication such as cream or butter (as an alternative, use sweet potatoes for a much less starchy mash)

- minced meat in dishes such as Bolognese sauce tends to have a somewhat awkward crumbly texture. It works better if you get lean mince from a butcher and ask them to mince it twice (the traditional Italian way), then puree the Bolognese sauce after cooking.

It also usually comes as a surprise that for many afflicted by dysphagia, the most difficult form of food to swallow are liquids. When considering the mechanics and the complicated process of swallowing, it becomes much clearer why that is the case. Fortunately, there are many different ways to thicken liquids and to turn them into jellies so that everybody can stay well hydrated, despite this swallowing challenge.

You may also find yourself repeatedly in a position of having to explain to well-meaning helpers and friends why mashed potatoes, or soft white bread, are such a sticky challenge, especially if you suffer from dry mouth. You will need to be generous and patient about this: it is hard to imagine dysphagia, or dry mouth or any similar oral-food processing problems for those who have not experienced such problems themselves. Try and communicate all this frankly to those who support you, it will help them to help you!

As a rule of thumb if you are able to swallow enough power drinks or supplements to keep going, try to feed yourself with enjoyable, proper, texture-adjusted foods, possibly enriched as much as possible (and consider power drinks and supplements as a plan B, or just as supplements to enrich your normal foods) – far more pleasure to be had from ‘real food’!

It may be useful to keep a food diary as this will give useful information about the calories and possibly missing nutrients in your daily food intake over a period of time.

Distorted taste / lack of appetite

Our senses of taste and smell are a complicated machinery, designed to distinguish bitter, salty, sweet, sour and umami (‘savoury’) flavours. When this machinery is compromised this can take many different forms. You may find that the smell of food puts you off, that everything tastes like saw dust, that some foods taste ‘wrong’ or give you a lingering bad taste in the mouth, and so on. Most importantly, make sure that these effects do not cause an aversion to eating altogether, there are ways to manage impaired taste – and even enjoy food.

Avoid off-putting foods and look for foods that at the time taste and smell good. These may be rather different from your normal favourite dishes and may include some apparently crazy combinations. Many find umami (savoury) tastes (and smells) most appetising. You may find that cold food tastes better. Be prepared that taste confusions change over time. What is revoltingly horrible this week may well be back on the agenda two weeks on. Keep on trying what works best and be prepared for sudden and surprising changes.

Only you can know what works for the moment and if somebody else helps you with the cooking, do let them know about your current preferences.

It is a good idea not to experiment with your favourite food(s) from the old days. It is very disappointing if, for the moment, you can’t enjoy it but can perfectly well remember how it should feel and taste. It may discourage you from eating altogether. Keep your favourite dishes from the old days on the list for later, to be re-visited when you are confident that you can actually enjoy them.

If the smell of food is a problem, eat cold and frozen foods. Ask somebody to help you with the cooking as that will minimise your exposure to the smell of foods. At the other extreme, you may find the intense aroma of essential oils helpful to improve your appetite. A lingering bad taste in the mouth can be counteracted by chewing on cloves, or just keeping them in the mouth.

Naturally we all have an appetite for refreshing acidic flavours such as that of lemons or oranges. If these are far too acidic to enjoy by mouth, make use of your nose as much of our flavour experiences actually stem from the smell of foods. Just clip a slice of lemon or orange on your cup or mug, that gets it close to your nose when you drink and can satisfy an appetite for a refreshing lemon flavour without causing problems with acidity.

Your taste buds are recovering, you are getting tired of bland foods but can’t handle spicy foods? Your kitchen window sill or your garden (or grocery shop) can help. Grow flavoursome herbs, lots of them (basil, lovage, mint, lemon balm, chives, flat-leafed parsley, sage, coriander, tarragon, dill all work well). If you can manage generous amounts of finely chopped fresh herbs in your food – just add these to your food before serving. Some people find that freshly chopped herbs are helpful with dry mouth troubles (that may be because of the (literally) mouth-watering properties of the smells of chopped fresh herbs). If you can’t, or don’t want to, have bits of chopped herbs in your food, you can add fresh herbs while cooking and simply pass your food through a sieve before serving it.

Should you be in the mood for a bit of kitchen experimentation, here is a little trick that also avoids having to remove bits of chopped fresh herbs from your food. Get yourself a rock-bottom cheap small Italian espresso jug (the version that you heat on your stove). Stuff roughly chopped herb leaves in the filter compartment (where normally the coffee powder would go), put a little bit of water in the bottom part as usual and heat briefly as you would normally do for making espresso. The rising steam extracts the flavour from the chopped leaves and you will have an intensely herb-flavoured infusion in the bottom part of the jug (the steam-treated leaves will look a bit sorry). Use that infusion to add flavour to your food (freeze any surplus in small portions for later use).

A selection of spices which add flavour and variety to your food without creating unpleasant sharpness / hotness are cloves, cardamom, bay leave, fennel seeds, coriander seeds, caraway seeds, ground nutmeg, cumin, star anise (see Figure 3). You can put the spices in a tea egg for easy removal after cooking.

There are two special candidates amongst the useful spices: cinnamon and vanilla (see Figure 4). Both of these are not only suitable for sweet dishes but are also delicious in savoury recipes (cinnamon is one of the main components of most curry powder / masala mixtures). An example would be the combination of fresh wilted spinach with a little butter and vanilla which is delicious. These two spices are special because their ‘taste’ to a large degree we actually notice by smelling rather than tasting them. That makes them useful candidates for flavouring food when your sense of taste is compromised but your sense of smell is working.

When spicy foods are problematic the most commonly troublesome spices are pepper (black more so than white), hot paprika, cayenne, any kind or form of chillies, hot curry-powder mixtures, vinegars, lime or lemon juice, hot mustard and horseradish (see Figure 5).

Tomatoes, peppers and some fruit (some varieties of tart apples, for example) can also be difficult because of their acidity. Using a spritz of lemon or lime juice, or a small amount of prepared mustard, to enhance the flavour of creamy sauces and soups or other dairy-based dishes normally does not cause any problems with acidity.

If everything tastes like saw dust, try tart foods and use strong flavours and spices, if you can manage those. Try enhancing the flavour of your food with lemon juice or other fruit juices, or wine if you can tolerate acidity.

If you feel that you need a break from dairy products, try almond, soy or coconut milk as an alternative.

Many people find red meats problematic, and most can enjoy food based on dairy, eggs, fish and white meats.

It is likely that a ‘normal’ / conventional three-meals-a-day pattern will not work particularly well while you find eating difficult. Ignore conventions and eat when you are ready, whatever you fancy within your comfort zone of food preparations at whatever time – there are no laws that enshrine eating times and composition of meals. If this can include the odd social occasion of sharing food / eating with others and sitting down together at the table, even better. You may discover that some children who normally refuse to eat vegetables are quite happy to eat wobbly, colourful vegetable jellies.