Cleft lip/palate

Contents

The general timing of surgery is outlined on the previous page. The precise details of the timing of surgery will vary depending on the individual patient and the treatment philosophy of the treating centre. The following discussion follows approximately the general timing patterns.

Lip repair

In general, neo-natal lip repair, that is very early lip repair has fallen into disrepute. Most surgeons will undertake lip repair between three and six months old. The classical rule was the rule of 10 which is still referred to (the child is 10 weeks old, 10 lb in weight, and has a haemoglobin level above 10 g/dl). In Germany the rule is that lip repair is not carried out before 3 months of age and not under 5 kg in weight. Usually at the age of 3 months, babies are 7 or 8 kg in maximum weight.

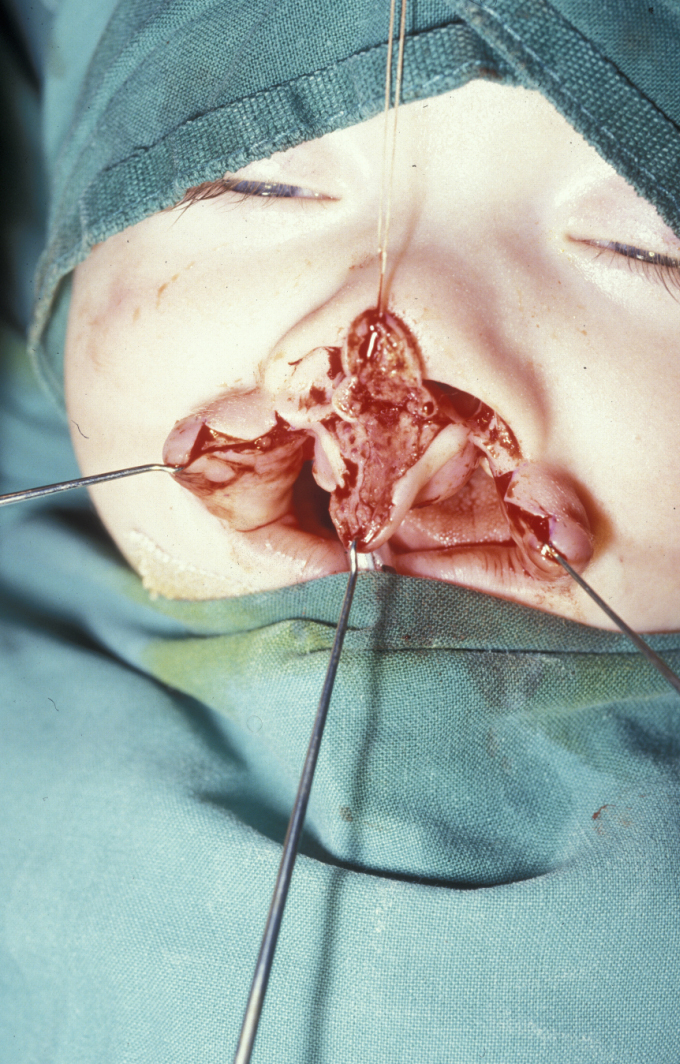

Numerous different surgical techniques for lip repair have been described. Perhaps the most important principles are reconstitution of the orbicularis musculature (a group of muscles in the lip), with the appropriate muscle attachments, of the alar base (base part of the nose), restoration of the white role and vermilion border (margin of the lip) and respecting the boundaries of labial skin, nasal skin and oral mucosa (Figure 1).

Some of the main controversies in this area of surgery are whether release and advancement of the muscle, skin and mucosa should be achieved by subperiosteal undermining or supraperiosteal undermining. The use of skin lengthening cuts by geometric design which transgress the actual skin boundaries or the allowance of the re-imposed muscle to stretch the skin within the natural skin boundaries is another area of controversy (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Dissection of the alar cartilage should be carried out to allow its repositioning, but there is controversy over the extent of cartilaginous dissection and so-called primary rhinoplasty, and some controversy remains over the use of a mucosal flap from the vomer (bony part of the septum of the nose) in order to reinforce the floor of the nasal cavity.

Palate repair

The technique popularised by Delaire undertook soft palate repair at the same time as lip repair to allow functional moulding of the residual cleft in the hard palate. This may or may not be practised, depending on the centre where the child is operated. Primary bone grafting of the alveolus has generally fallen into disrepute.

Closure of the palate in the UK is generally done relatively early. The principle here is to attempt to close the palate before the development of speech and a hypernasal speech pattern. In some European countries, closure of the hard palate is delayed in order to minimise the unwanted effects of early surgery upon growth. This delay may improve transverse growth of the maxilla but there is an obvious compromise in terms of speech development. In Germany, there are also many different concepts concerning sequence and timing of the operation. The common opinion is that the palate should be closed at the age of 2 years at the latest.

Palatal closure by common consensus is now carried out using techniques which leave minimum stripped palatal mucoperiosteum and exposed bone in an attempt to decrease scarring and the unwanted effects on growth (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Primary dentition and speech assessment

The development of the primary dentition should be allowed to progress essentially naturally with good paediatric dentistry in order to maintain space. No orthodontic intervention in the primary dentition is warranted, but good preventive dentistry is. A joint ear, nose and throat and speech therapy assessment should be carried out to detect middle ear effusions (glue ear) and appropriate development of speech patterns. Hypernasal speech and / or glue ear should be addressed, either by therapy or surgery such as pharyngoplasty or myringotomy (for glue ear).

Mixed dentition

At this stage the growth-retarding effects of initial surgery become more evident, seen predominately transversely in the upper arch and then anteroposteriorly as growth in this dimension predominates with age. The eruption of the permanent incisors demonstrates defects in enamel formation and position, and the upper incisors may erupt into lingual occlusion. Orthodontic preparation for alveolar bone grafting (see below) can usefully be combined with limited alignment of the incisors in the mixed dentition. Operation for alveolar bone grafting generally requires expansion of the maxillary arch and preferably alignment of the segments. There is an advantage to increasing the size of the alveolar defect. This allows adequate working space within the defect to recreate the nasal floor and oral mucosal layer, with cancellous (spongy) bone sandwiched between the two layers and the anterior component closed by a sliding buccal mucosal flap.

Alveolar bone grafting

This technique provides bone through which a permanent canine and lateral incisor can erupt into the arch. The procedure unifies the maxilla providing a stable intact arch, improves the alar base support, closes the residual oronasal fistula and provides a palatal base for later orthognathic surgery.

Initial assessment for alveolar bone grafting should be carried out at the age of 8 years as in rare instances it may be possible to graft to allow an intact lateral incisor to erupt. More commonly the lateral incisor is rudimentary or missing or may have to be removed as part of the bone grafting procedure. In this instance the actual timing of the bone graft is predicated on the state of development of the canine tooth

Collaboration with the orthodontist on this is essential, both in terms of timing of the bone graft and in terms of arch expansion and stabilisation of the maxilla. Particularly in cases of bilateral alveolar bone grafting, the premaxilla should be stabilised with a heavy arch wire and either a tri- or quad-helix (a heavy wire orthodontic appliance). This provides optimum stability for the grafted bone. Preoperative removal of deciduous teeth and visible supernumerary teeth six weeks prior to alveolar bone grafting creates healthy attached gingivae and optimises the flap design.

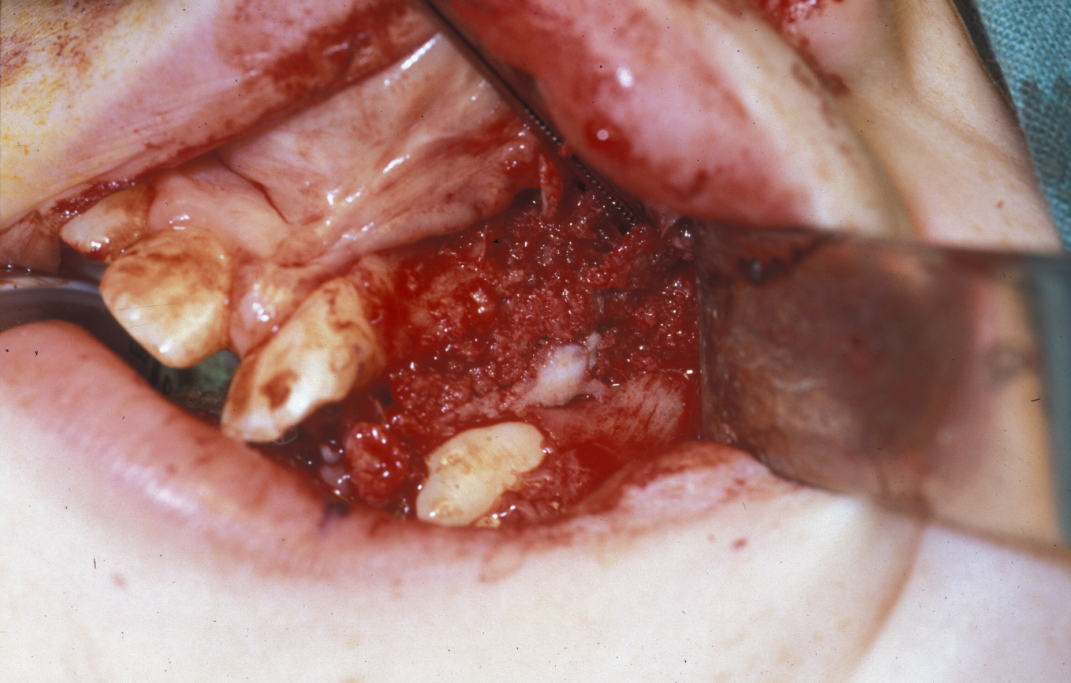

The technique of alveolar bone grafting involves outlining a buccal lesser flap and a major segment flaps. The flap in the major segment is a mini-flap. Subperiosteal dissection exposes the cleft and the lining of the oronasal fistula is incised to create two upper nasal flaps and two lower palatal flaps. These flaps are sutured to create a pyramidal shaped defect now lined by mucosa superiorly and inferiorly. This defect has either periosteum or bone on all its margins at this point, except for the base which is the labial aspect. The defect is then packed with bone which may be trephined or harvested by an open procedure from the iliac crest (hip) or the tibia (lower leg) (Figure 6).

Skull and chin bone are popular in some centres. The bone used should be cancellous bone as this has the greatest propensity to become alveolar bone and allow migration of the canine through it. There is no good evidence to support the use of synthetic materials for this procedure. The periosteum of the lesser segment (larger) buccal flap is then incised and advanced to close the labial defect. It is important to remember that bone will not take against exposed cementum. Therefore, any obviously exposed root (for example from a supernumerary tooth or a residual lateral incisor), should result in removal of that tooth, rather than compromising the bone graft (Figure 7).

Prophylactic anti-staphylococcal antibacterial agents (such as ampicillin or flucloxacillin), topical antiseptics (chlorhexidine orally and nasally, or mupirocin nasally) and local analgesia at donor and recipient site both improve success and comfort.

Permanent dentition

The establishment of the permanent dentition, including guiding of the canines, which have to be exposed in about 15 % of cases, is basically a decision as to whether orthodontic camouflage or orthognathic surgery is indicated. If orthognathic surgery is indicated, standard orthodontic decompensation is carried out and the osteotomies are relatively conservative antero-posterior movements. The chances of advancing a cleft maxilla further than 7 mm without significant relapse is very small (Figure 8, left) and it is customary to balance the movements in the maxilla and the mandible (Figure 8, right) in order to achieve an optimum facial balance and occlusion. Once the maxilla is stabilised, further completion surgery can be carried out.

Rhinoplasty

Rhinoplasty should be performed at the end of treatment rather than as an intermediary, because the final position of the nose can only be predicted once the maxilla is in a stable position. Open rhinoplasty techniques have been popularised in addressing the cleft nose principally because the dome of the nose, made up from alar cartilage is frequently bifid and the collumella (bottom part of the septum of the nose) is short. This allows access to the alar cartridges of the dome to allow primary refashioning and suturing.

Definitive restorative dentistry

Implant-borne permanent prosthesis, or fixed-bridge prosthesis, which can allow optimal oral hygiene should allow full and final rehabilitation.