Damage

This page gives a general overview of procedures and approaches in repairing soft tissue damage in the head and neck area.

Initial steps

The initial treatment steps include a thorough exploration of the wound(s) and other structures, as well as stopping bleeding.

Gaping penetrating wounds of the neck (see Figure 1; deep to the platysma, the large but thin muscle covering the front middle and sides of the neck) need to be explored in an operating theatre environment.

Blood vessels need to be checked for bleeding (often blood vessels that were only partially transected, or blood vessels (often completely transected) in a spasm). Damaged blood vessels are repaired by ligating them (tied up) or by using diathermy (using heat to cause clotting). Vital blood vessels are repaired by using fine sutures (stitches) as required.

There is a range of methods of treating haemorrhage (stopping bleeding):

- application of direct pressure (all types of bleeds)

- vasoconstrictors (for example adrenaline which has a temporary and reversible effect)

- haemostatic agents (speeding up the clotting of blood, or providing an artificial clot), for example fibrin-based products for topical application, or tranexamic acid for systemic application

- diathermy, cautery or coblation (removal of tissue by low-temperature plasma technique)

- ligation (small vessels)

- microsurgical vascular repair (large or major vessels).

Similar to blood vessels, nerves that have been partially or completely divided may require microsurgical repair, either by directly connecting the proximal and distal ends, or by using a nerve graft.

Other structures and organs in the face that may be involved in a wound are the eyes (see Figure 2), ears or salivary glands.

It is obviously important to identify and repair such underlying damage, failure to do so could result in long term morbidity (ongoing problems). A scalp laceration may overlie a skull fracture, a black eye may overlie an orbital / zygomatic (cheek bone) fracture, and a facial laceration may overlie a parotid (major salivary gland near / in front of ear) duct laceration, facial nerve laceration or underlying fracture.

Other investigations

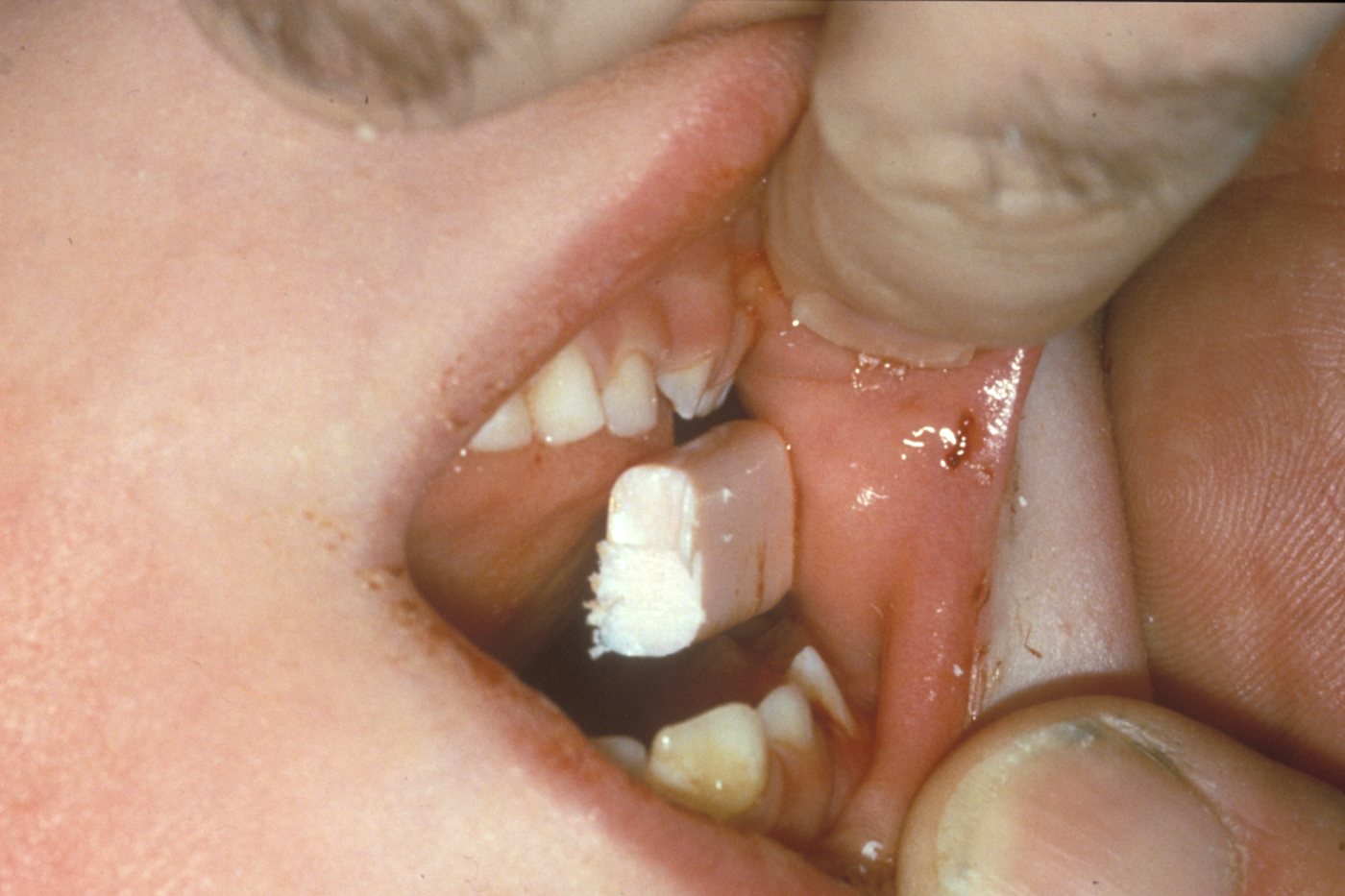

Foreign bodies: if the mechanism of injury suggests a left behind foreign body (tooth, glass, dirt, projectile), then radiographs taken from two directions are used for localisation (see Figure 3). Some foreign bodies may be more obvious, see Figure 4. Some foreign bodies are not straightforward to detect by imaging methods: organic structures like wood can be confusing and thin hollow plastic objects may resemble air pockets on CT scans.

Depending on size, location, nature and toxicity, most foreign bodies will require removal. In certain circumstances, it may be acceptable to leave inaccessible or innocuous objects; shotgun pellets are such an example.

Infection: swabs for culture and sensitivity will provide baseline information but rarely actually influence treatment. Most traumatic soft tissue wounds should have the bacterial contamination treated by surface cleansing (see below) and a broad-spectrum antistaphylococcal antibiotic.

Large complicated or deeply contaminated wounds are best treated under general anaesthesia. Most wounds and all complex wounds in children (see Figure 5) are best treated using general anaesthesia.

Frankly infected wounds, or wounds with a high likelihood of infection are sometimes best left dressed with an antiseptic dressing; antibiotics are given and the wounds are closed once clean.

Wound cleansing

Cleaning the wounds is the most important stage in reducing the risk of infection and preventing possible ‘tattooing’ of the tissues by debris such as gravel which may have become impacted in or around the wound. There are a variety of cleansing solutions available. It is not a good idea to compromise adequate cleaning of wounds just to avoid general anaesthesia.

General method of cleansing involves:

- aseptic scrub

- a suitable antiseptic solution is applied to a sterile gauze swab, held in forceps

- the swab is applied to the skin closest to the wound and is used to clean the periphery of the wound in an increasing radius; the swab is then discarded

- any impacted material can be removed by surgical forceps or with a surgical scrubbing brush, dipped in antiseptic solution

- the wound is explored again for further foreign material and tissue damage

- any small areas of necrotic (dead) tissue or tags of ischaemic (lacking blood supply) tissue are trimmed with sharp scissors or a scalpel

- the wound can then be irrigated with normal saline and is ready for closure.

Wound closure

This should always be performed in a good light and preferably with assistance (closure of wounds often requires the hands of more than one operator). The patient should be positioned supine (lying on the back) even when local anaesthesia is used, to minimise the risk of a faint.

There is a considerable choice of materials for wound closure:

- adhesive paper strips (most useful for small wounds in areas where skin tension is not excessive)

- tissue glue (most useful for superficial, uncomplicated skin wounds with little skin tension; popular for treating children because no anaesthesia for placement and no removal of sutures is needed)

- sutures (there are many types and strengths of suture material, resorbable as well as non-resorbable; suture material needs to be chosen to match the defect that needs closing)

- staples (these are rarely if ever used on the face).

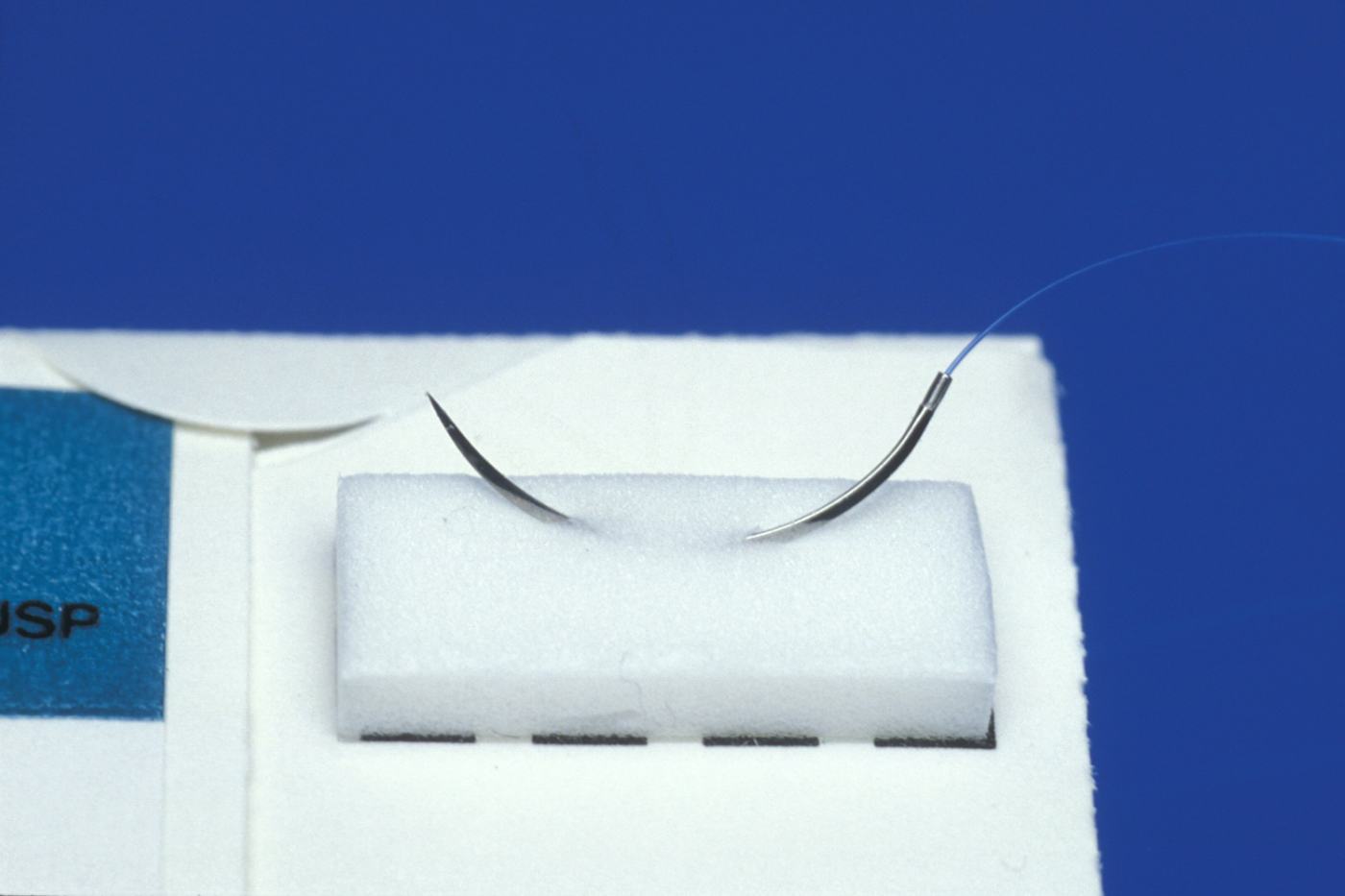

Suture material and its strength have to match the defect that needs closing. Tight immobile wounds require thicker sutures; delicate, lax areas require fine stitches (see Figure 6 for an example).

Resorbable sutures may occasionally be used to close skin wounds in children where removal at a later date would necessitate another anaesthetic. Resorbable sutures are used in deep layer closure (see below) routinely and in inaccessible sites. They can play a useful role in subcuticular (under the skin) closure techniques.

Staples can be used as an effective method of closure of the skin surface in simple larger wounds. They are removed using a staple remover which is often less uncomfortable than removing sutures.

Removal of sutures

All sutures, being foreign bodies, cause irritation to the tissues and hence have the potential to cause scarring. Skin sutures are removed as soon as tissue healing allows, preventing further irritation of the tissues and avoiding binding of the sutures to the tissues as they heal.

As a rough guide non-resorbable sutures are best removed from the face at a period of five or six days, when sufficient healing has usually taken place to allow function of the tissue without re-opening of the wound.

Wound closure with sutures (wounds without tissue loss)

Where there has been little or no tissue loss and the margins of the wound consist of viable (healthy and stable) tissue, primary closure with sutures can usually be achieved.

Commonly used techniques are

Interrupted sutures are the simplest type of suture but also tend to be the most time consuming. Individual interrupted sutures can be used to close points of apposition in wounds until the entire length of the wound is closed (see Figure 7).

Interrupted sutures are most useful for closing wounds of irregular contour and have the advantage that the closure of the entire wound is not dependent on just one suture (see Figure 8).

Continuous sutures are useful for closing straight wounds where tissue apposition is easy to achieve with accuracy (see Figure 9).

There is no interruption to the course of the suture, giving this suture the advantage of being less time consuming and possibly creating a more evenly balanced force of closure on the tissues. However, continuous sutures have the disadvantage that the whole layer of wound closure is dependent on just one suture, and therefore failure may mean re-suturing of the entire wound. Continuous sutures also tend only to be useful for closure of straight wounds.

Layered closure is a suitable approach for deep wounds, where tissue should be closed in layers to remove dead space and confer strength to the wound.

The technique for layered closure involves closing the deeper tissues first, usually with a continuous suture or ‘buried’ (resorbable) interrupted sutures, and then closing the skin with interrupted sutures (or occasionally adhesive strips) as above.

Deep or extensive wounds may require the insertion of a drain, which lies along the length of the depth of the wound. The purpose of a drain is to remove excessive inflammatory exudate and ‘oozed’ blood from the wound to prevent it collecting as a focus for infection. A drain placed in a wound is usually exited via an area of intact skin and subcutaneous tissue and may cause a small scar at that exit point following removal. Drains are usually made from plastic tubing which is perforated along the section lying within the wound to allow inflow of fluid. The outer portion of tubing remains intact and can be attached to a container (usually vacuumed) to collect and monitor the out-flowing fluid.

Wounds with tissue loss

In cases with tissue loss, occasionally the surrounding tissues are sufficiently elastic to allow them to be advanced into the area of defect and achieve functional and aesthetic closure. Where a substantial amount of tissue loss has occurred such that closure of the defect without excessive tension on the tissues cannot be achieved or would cause disfigurement, there are several options available for treatment.

Undermining the skin: when tissue loss is not extensive and mainly involves skin, a small border of skin either side of the wound may be carefully separated from the underlying fat. This allows advancement of the released elastic skin across the wound. Specific areas of the face are suitable for this technique.

Partial closure / granulation: this involves suturing the wound such that it is partially closed and not under excessive tension. The resulting defect is then allowed to heal by granulation. This technique is suitable for smaller defects but tends to increase the level of scarring; therefore it is usually inappropriate for facial wounds.

Skin grafting: this is used when mainly large areas of skin have been lost. It is often possible to harvest skin from a donor site elsewhere in the body for placement over the wounded area. Skin can be taken in a partial or full thickness graft from a site such as the inner thigh or arm (split thickness) or supraclavicular (above the collarbone), pre- or post-auricular (near the ears) regions (full thickness). The donated skin may be meshed (multiply punctured to allow stretching of the skin over a wider area, the epithelium spreading into the small resulting defects as healing occurs). Skin colour varies across the body and therefore care must be taken to ensure that the donor site is a reasonable match to the recipient site (see Figure 10).

Local flap repair: it may be possible to utilise skin from an area local to the defect by means of raising a flap of skin and repositioning it to cover the defect. This requires some ‘give’ in the skin at the donor site and therefore may require wide undermining of the skin in areas where the skin and underlying tissues are under tension or tightly bound to underlying structures (for example, the scalp). Common designs of flap for repair of defects include rotation and advancement flaps.

Local tissue can be augmented by local tissue expansion (see Figure 11). This takes time but creates a large amount of surplus local tissue for wound repair which gives close to the ideal colour and texture match.

Distant flap repair: this involves removing donor tissue, including vasculature (blood vessels) from a distant body site and anastomosing (connecting) the vessels to the vasculature of the recipient site prior to repair.

There is a small risk that the circulation in the ‘free flap’ will fail (usually due to thrombosis in the venous system) and this is generally a more time consuming and complex operation. This repair method should be reserved for areas where there is extensive tissue loss and local flap repair would not suffice.

After damage repair: wound healing, scarring and potential problems

Following tissue trauma, there is an initial acute inflammatory response until fibrous tissue in the wound eventually matures to form a ‘scar’. A number of factors affect the wound healing process, including:

- site of the wound (tissue, blood perfusion, movement, and so on)

- timing of treatment

- nature of treatment (correct or incorrect technique)

- systemic factors (age, health, nutrition, use of steroids, and so on)

- infection.

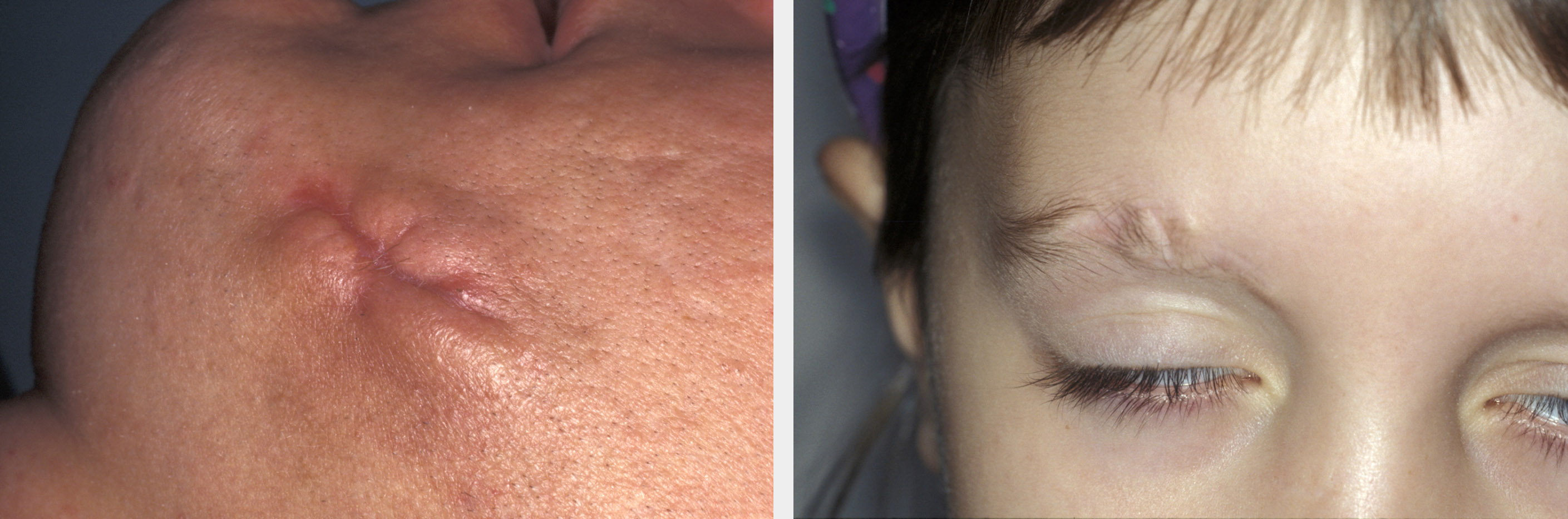

Almost every injury involving a breach of the skin will result in a degree of scarring. In many circumstances, scars are in areas where they will not readily be noticed by other people and therefore they are of little or no consequence. Indeed, even in clearly visible areas, scars are often so fine as to be barely noticeable, or may be disguised within the natural skin creases or relaxed skin tension lines. Elective incisions for surgery are designed such that they respect the relaxed skin tension lines and so produce as minimal scarring as possible. However, trauma has no respect of aesthetics and therefore the scar produced by a trauma wound may prove to be particularly unsightly. Linear wounds tend to develop more obvious scarring than do irregular wounds unless a linear repair eyebrow has been mismatched (see Figure 12. Good wound care, early suture removal, moisturisation and massage all help to reduce scarring.

Non-surgical techniques to improve scars include silicone based gels for self-application, silicon pressure dressings, application of intra-lesional steroids or steroid impregnated tape.

If a scar is particularly aesthetically disturbing, it may be possible to perform ‘scar revision’, that is to surgically modify the scar such that it is reduced or is aesthetically disguised. There are a variety of techniques for such purposes and it is essential that the timing for such corrective interventions is well chosen: it usually takes about 18 months for a scar to be fully matured. Ideally scar revision should not be undertaken any earlier than that.

The most common problems following soft tissue damage repair are various forms of wound infection. Common reasons for infection(s) include:

Pre-operatively:

- wound contamination with microorganisms at the time of trauma

- delay in treatment

Post-operatively:

- contamination at the time of injury

- poor cleansing / wound debridement or poor aseptic operative technique

- poor closure of the wound

- failure to administer appropriate ‘prophylactic’ antibiotics

- host susceptibility.