Bone lesion

This section takes a slightly closer look at, and gives an overview of, the three main categories of bone lesions:

- inflammatory and other non-neoplastic lesions (including bone infections)

- benign neoplastic lesions (benign lumps)

- malignant neoplastic lesions (bone cancers).

Inflammatory and other non-neoplastic bone lesions

Inflammatory conditions of the jaws are a puzzling and difficult to manage group of conditions that do not fall into any particular or easy category. Other non-neoplastic bone lesions are an equally puzzling group of hereditary and acquired conditions.

Dry Socket

Pain after breakdown of the healing blood clot following tooth extraction is by far the most common inflammatory bone lesion in the head and neck region. Even this common condition has excited a fair amount of controversy.

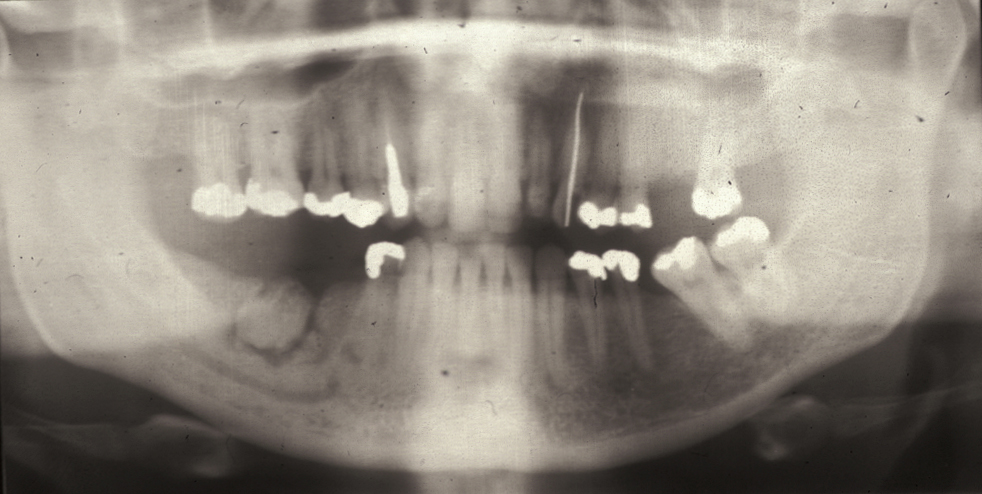

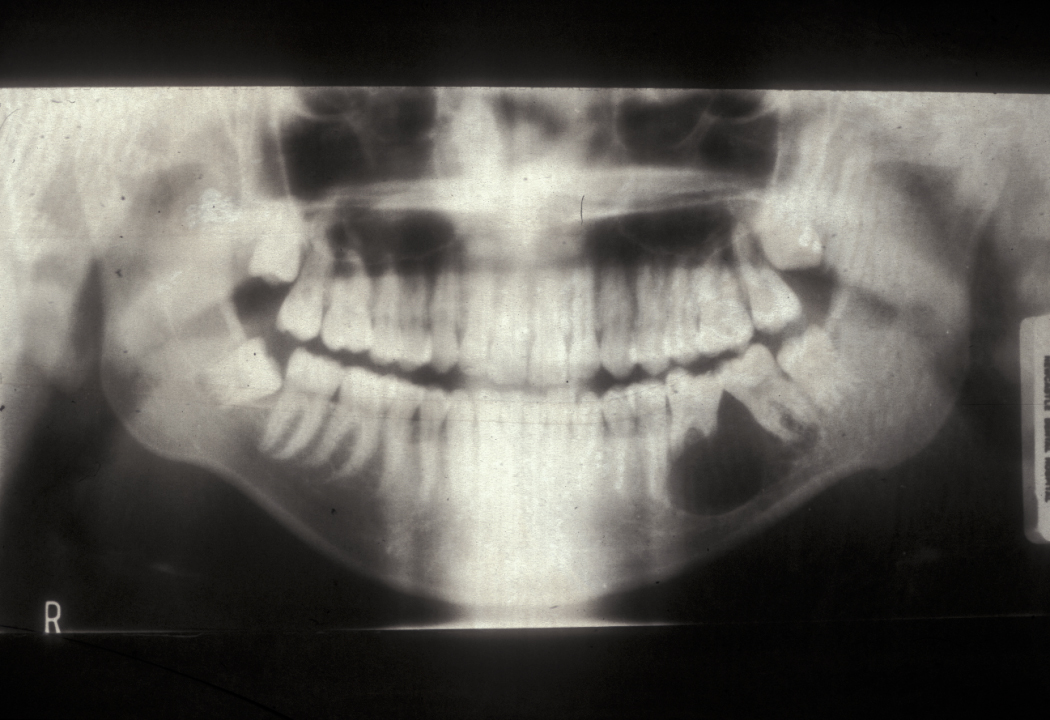

This condition has a number of different names and it occurs in approximately 3 % of routine tooth extractions, and up to 20 % of surgical tooth extractions. Figure 1 shows a dry socket, Figure 2 shows the radiograph of a severe case of dry socket.

The pain is localised to the site of extraction, is often throbbing and very severe. It will often keep you awake at night. The classical description is of a toothache that never went away when the tooth was removed. Some dry sockets may start after the tooth has been removed and the pain does not commence until the healing blood clot has completely broken down and established bone inflammation has started. Some patients benefit from the use of standard non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (such as ibuprofen), but the pain can often be so severe that these analgesics do not really help.

Osteomyelitis

The term osteomyelitis covers a range of acute and chronic inflammatory bone conditions that usually originate from some kind of bacterial infection. It starts in the medullary space (central cavity of bones, where the bone marrow is located) and progresses as inflammatory changes in the nutrient (blood) vessels render the bone ischaemic (suffering from insufficient blood flow). Any pus formed can compress the vessels further. As a consequence, the bone becomes necrotic (the bone tissue is dying) and behaves like a foreign body, known as a sequestrum. This gives rise to a chronic inflammatory reaction as the body tries to eliminate the sequestrum. Continued attempts at repair may result in the sequestrum becoming encased in bone material, known as involucrum.

Imaging may be difficult because the radiographic findings lag behind the clinical stage. The first radiographic sign (see Figure 3) may be radiopacity which represents the sequestrum that has lost its non-mineralised components. Bone scans (PET scans) show osteomyelitis as areas of increased bone turnover (‘hot spots’).

Osteomyelitis can be divided into suppurative (producing pus) or non-suppurative (not producing pus) forms, although these two forms may overlap considerably. There is frequently a predisposing factor for the development of osteomyelitis. This may be some underlying systemic disease (such as an autoimmune disorder) or local bony factors. The local bony factors include primary diseases of bone, such as fibrous dysplasia, Paget’s disease or osteopetrosis (for these conditions, see below). Osteomyelitis may also be secondary to bone damage from trauma or foreign bodies in the bone, such as bone plates.

In the maxillofacial region, osteomyelitis is most commonly seen in the mandible (lower jaw) and is usually secondary to an odontogenic (tooth related) infection. Rarely, in infants there may be an acute infection of the maxilla (upper jaw). This is more correctly known as osteitis as the medullary space (where osteomyelitis commonly develops) in the maxilla is negligible. Instead, the infection is thought to reach the maxilla via the blood stream (a haematogenous route). The infection is most commonly poly-microbial (caused by several types of microorganisms) with staphylococci predominating. Salmonella is commonly implicated in those cases of osteomyelitis occurring in patients with sickle cell disease (a disorder of the red blood cells).

Infection is not the only possible cause of necrosis of bone. Cells in bone exposed to high-energy radiation during radiotherapy will have suffered DNA damage and will break down when required to undergo replication (osteoradionecrosis, ORN). This necrotic bone is very susceptible to secondary infection.

Some medicinal drugs used to treat / manage osteoporosis (brittle bones) or bone metastases (bisphosphonates, anti-angiogenic drugs and anti-rank ligand antibodies (denosumab, a human monoclonal antibody), respectively) render bone incapable of normal physiological healing by reducing the activity of bone renewal. In this situation bone is also very prone to superinfection. As the bone cannot respond to infection, this can give rise to a specific, drug-related kind of osteomyelitis.

Both types of drugs, bisphosphonates and anti-rank ligand antibodies, hinder the osteoclasts (the cells that break down old bone tissue, before osteoblasts start regenerating bone by producing new material); anti-rank ligand antibodies effectively paralyse osteoclasts. This drug-related kind of osteomyelitis is usually referred to as medication related osteonecrosis of the jaws (MRONJ).

Some anti-angiogenic drugs (drugs hindering or preventing the formation of blood vessels; used in some cancer treatment schemes alongside more traditional chemotherapy) can cause a very similar condition.

Cysts

Cysts are pathological cavities that are lined with epithelium (the kind of tissue that covers the body’s various surfaces) and are filled with fluid, air or semi-solids. A wide variety of cysts of different origins occur in the head and neck region, in particular the jaws, including some fluid-filled cavities in bone that are not lined by epithelium (so called pseudo-cysts).

Fibrous dysplasia

This is characteristically a disease of young adults in which areas of bone are replaced by fibrous (scar-like) tissue. Onset is in childhood and the disease tends to stabilise with age. Fibrous dysplasia weakens the affected bone(s) and can lead to fractures, deformity (dysplasia), pain and loss of functions, depending on location(s).

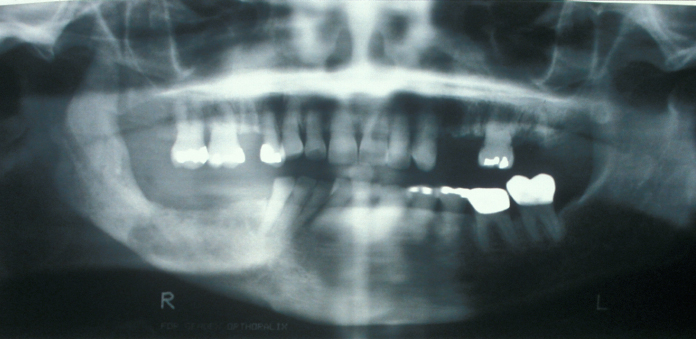

Jaw involvement usually manifests as a hard, painless swelling with a characteristic radiograph appearance of ‘ground glass’ (see Figure 4).

Histology shows fibrous replacement of bone with osseous trabeculae (spongy bone structure) that look like Chinese characters. It is thought that fibrous dysplasia may be caused by a non-hereditary genetic mutation that occurs at the early embryonal development stage for unknown reasons.

Cherubism is a hereditary variant of fibrous dysplasia that manifests between 2 and 4 years of age. It appears bilaterally within the maxilla and/or mandible, causing expansion of the jaw bones and swelling of the face; in severe cases functional impairment may result. Cherubism tends to burn out in a similar fashion to fibrous dysplasia with age.

Ossifying fibroma is probably a localised variant of fibrous dysplasia that appears clinically as a bony hard mass in the jaws. It is capable of enlarging both bony cortices (the hard outer layer of bone) and appears well circumscribed radiologically.

Osteopetrosis

Osteopetrosis (marble bone disease) is a hereditary bone disorder that causes bones to harden and densify, leading to fractures, deformity (dysplasia), pain and loss of functions, depending on location(s). Despite the hardening and deposition of excessive bony material, affected bones are prone to fractures.

It is thought that dysfunction of the osteoclasts (cells responsible for breaking down worn bone cells in the bone remodelling process) is responsible for the disease. The resulting osteosclerosis (abnormal hardness and density of bone) can result from a number of different causes, not just osteopetrosis and thus requires careful investigations to support the diagnosis.

Paget’s disease of the bone

This multisystem condition affects the skull, pelvis and long bones as well as the jaws. In the northern hemisphere it is relatively common after the age of 55 years. A number of virus infections have been indicated as causes of the condition, although this correlation is unclear. There may be genetic hereditary factors and some involvement of vitamin D has also been suggested but ultimately the cause of Paget’s disease is not yet known.

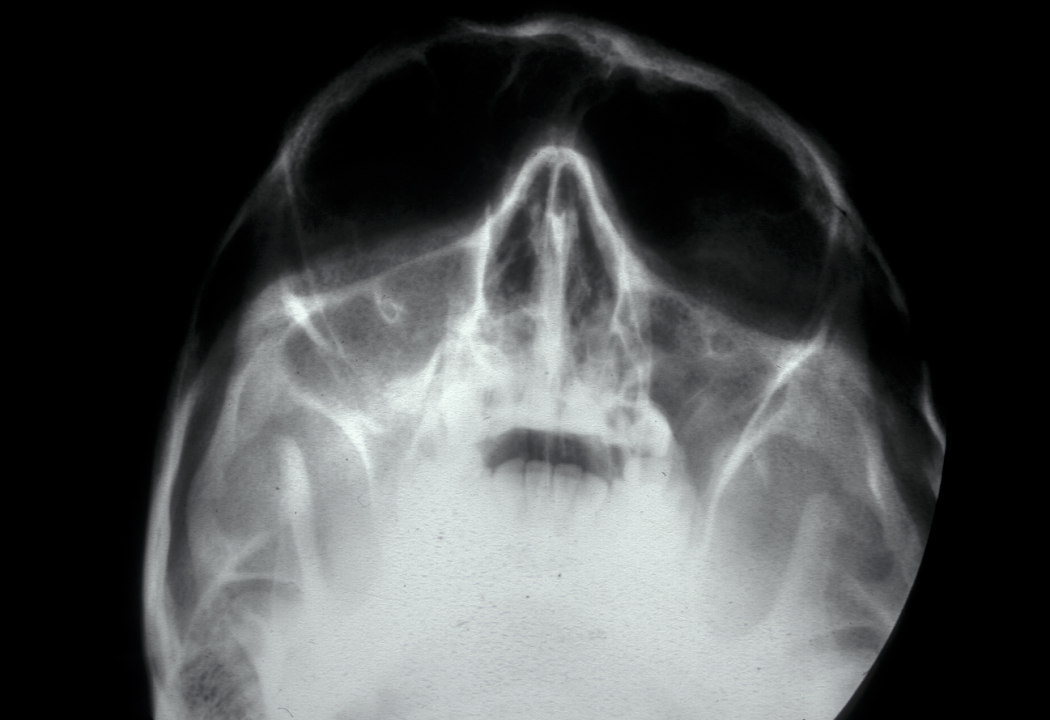

Paget’s disease of the bone is an imbalance in the bone remodelling process. Initial excessive break-down of bone tissue by overactive large osteoclasts (osteolysis) is followed by reactive chaotic increased production of bone tissue. This replacement of the normal bone remodelling process by a chaotic alternation of resorption and deposition leads to weakened, distorted bones (see Figure 5).

Bone pain and cranial neuropathies (malfunction and impairments of nerves in the skull) can occur, there may be altered sensation of the face in the affected region. Plain X-ray images show a cotton wool appearance of the affected bone; blood and urine tests show elevated levels of some characteristic markers (alkaline phosphatase and urinary hydroxyproline). Rarely Paget’s disease of the bone develops to a primary bone malignancy (osteosarcoma; see below).

Benign neoplastic bone lesions (benign bone tumours)

The majority of bone tumours are benign. Some are lesions that can occur in soft or hard tissues (or both) whereas others are specific to bone tissue,

In the absence of any convincing, technical ordering principle for these kinds of lesions, we resort to listing these conditions in alphabetical order.

Ameloblastoma

This is the most common tumour of dental epithelial origin. It is found particularly in the posterior mandible in African males. Ameloblastoma is a benign tumour and has three clinical and histological variants – unicystic, follicular/plexiform and peripheral.

Unicystic ameloblastoma is a cystic swelling distinguished by resorbing adjacent tooth roots: histologically the lesion is an ameloblastoma but it has predominantly fluid contents. Figure 4 shows an example.

Follicular/plexiform ameloblastoma is a solid tumour, again found in the mandible. It is more aggressive in its clinical behaviour and resembles a solid tumour histologically (see Figure 5).

Peripheral ameloblastoma is an extraosseous soft tissue version of ameloblastoma. It is rare and is more often seen in the maxilla.

Ameloblastic carcinoma is a malignant version of ameloblastoma, other odontogenic benign tumours (adenomyoblastoma, myxoma, ameloblastic fibroma) are extremely rare.

Bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation (Nora’s lesion)

Bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation (Nora’s lesion; after the clinician Nora who first described the condition) is a rare benign bone tumour. It affects the cartilage and surface (cortex and periosteum) tissues of bones and usually afflicts the small bones in hands and feet of young adults, less commonly it is observed in the skull bones including the jaws. It is a generally painful, rapidly growing tumour; it is unknown what causes this lesion. Because of the typically rapid and locally aggressive growth, it is important to distinguish this lesion from malignant bone tumours such as osteosarcoma or chondrosarcoma (see below). This distinction is usually achieved by obtaining a biopsy. Depending on the location and size of the lesion it can cause signs and symptoms of compressing nerves in the vicinity.

Giant cell granuloma of bone

Giant cell granuloma is a benign lesion that can affect soft tissues as well as hard tissue. In bone, giant cell granuloma can manifest as an intrabony swelling.

Osteochondroma

An osteochondroma is a benign bone lesion, originating from cartilage and producing an outgrowth (exostosis) on the bone surface. Osteochondroma is the most common benign bone tumour; its most common locations are the long bones in the legs, the pelvis and the shoulder blade. Osteochondroma can occur as a single lesion (the majority of cases) or as multiple lesions; it mostly affects young adults.

Osteoma / Gardner’s syndrome

An osteoma is a mature benign bony growth with the most common locations being the skull bones, the mandible and the paranasal sinus (spaces surrounding the nasal cavity). The cause is not known. Osteoma may appear as a single lesion (see Figure 8)

or as small multiple bony protuberances. These are characteristic of Gardner’s syndrome. Gardner’s syndrome is a genetic disorder (multiple familial polyposis coli) which usually causes multiple benign tumours to form in different organs, particularly the colon. Gardner’s syndrome is thought to carry an increased risk of developing colorectal malignancies in the long term.

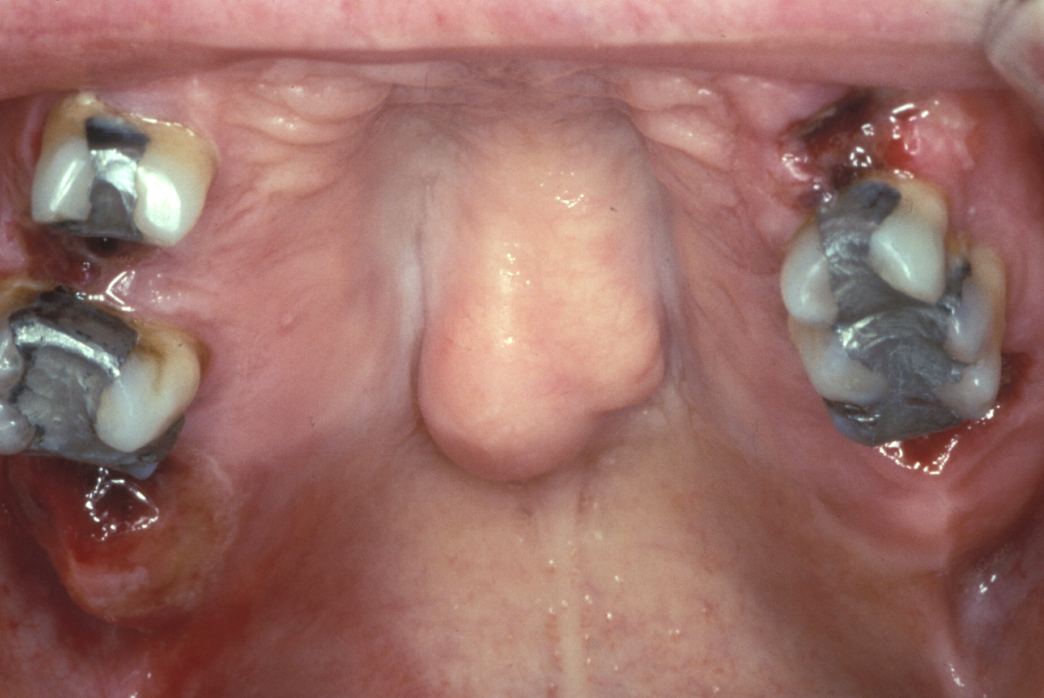

Torus

A torus is a bony exostosis (outgrowth) of the jaw. Torus palatinus occurs in the centre of the hard palate (see Figure 9), torus mandibularis occurs in the lingual (tongue-side) premolar or molar region of the mandible (see Figure 10). These lesions are entirely benign and only require removal when they are symptomatic or for reasons of prosthetic functionality.

Malignant neoplastic bone lesions (bone cancers)

Most primary malignant neoplastic bone lesions belong to the sarcoma category: a sarcoma is a malignant growth that originates from cells that were formed from the mesenchyme, a connective tissue that is present during foetal development. Much of the musculoskeletal system (cancellous bone, cartilage, fat and muscles) develops from this foetal tissue. Carcinoma refers to a malignant growth that arises from epithelial cells (cells in the tissues that line the surfaces and cavities of the body and its organs).

Primary malignant bone lesions are rare whereas metastases (secondary malignant growths from other primary malignancies) originating from more common cancers (breast, prostate and lung cancers in particular) show a tendency to affect bones.

A number of primary malignant bone lesions are typically malignancies of children and young adults but can occur at all ages. Generally, the head and neck region is not the most common location of most primary (and secondary) malignant bone lesions.

Some primary malignant bone lesions relevant in the head & neck region

Osteosarcoma is histologically the most common form of primary malignant bone lesions, mostly affecting young adults (because it tends to occur in growing bones) with the most common locations around knee and hip, but is also observed in the jaw. Osteosarcoma tends to be an aggressive, fast growing (high grade) malignancy with a tendency of forming metastases (spreading).

Osteogenic sarcoma in cystic cavities is a rare variant of osteosarcoma. It is mostly composed of blood-filled cystic spaces and necrotic (dead) tumour tissue, leads to severe bone destruction and has a tendency to form metastases mostly in the lungs, similar to osteosarcoma. It is thought that osteogenic sarcoma growth is so fast that local growth of blood supply vessels cannot keep up; part of the tumour hence dies, forming characteristic blood-filled cystic cavities and necrotic tissue in the process. This type of malignant bone lesion can sometimes appear similar to the changes observed for a benign lesion, an aneurysmal bone cyst.

Ewing sarcoma is the second most common primary malignant bone lesion mostly afflicting children and young adults. It originates from the inner cavity of bones (the medullary space) and, similar to osteosarcoma, causes severe bone destruction alongside inflammation of the periosteum (dense connective tissue enveloping bones), and has a propensity to form metastases. Ewing sarcoma only rarely occurs in the skull and facial bones.

Chondrosarcoma is a malignant bone lesion that originates from cartilage tissue; about a third of malignant bone lesions of the skeleton belong to this category. Whereas most other primary malignant bone lesions tend to afflict mostly younger people, chondrosarcoma occurs at all ages.