Vascular abnormalities

Below we summarise common signs and symptoms of the various vascular abnormalities, haemangiomata and vascular malformations. These lesions can occur everywhere in the body but the majority are located in the head & neck region, especially haemangioma. Vascular abnormalities are congenital malformations which in the majority of cases are sporadic (occur spontaneously); the occurrence of vascular abnormalities as an inherited condition, or as part of an inherited syndrome, is very rare.

Our discussion is focussed on vascular abnormalities in the maxillofacial region. We follow the generally accepted classification of these malformations, which subdivides the lesions into vascular tumours (including haemangioma and pyogenic granuloma) and vascular malformations (of the blood and lymphatic systems). It is important to arrive at a precise diagnosis, as the treatment schemes differ for the different types of vascular abnormalities.

Haemangioma

These benign vascular tumours are made up of rapidly proliferating endothelial cells (lining of blood vessels) and, in consequence, lead to malfunctioning sections of blood vessels. A superficial, visible lesion on the skin may only be part of a more extended lesion, reaching into deeper tissue layers. When the lesion has well-defined boundaries, it is called a focal haemangioma. Some haemangiomata lack such boundaries and consist of multiple, interconnected lesions (segmental haemangioma). Segmental haemangioma often is distributed over the region of the trigeminal nerve (one of the cranial nerves) and extends to deeper layers of the parotid gland (one of the major salivary glands) and other deep fascial planes in the head and neck. Such segmental haemangioma often has a beard-like appearance and may involve the airway.

Haemangiomata are further subdivided into infantile haemangiomata and congenital haemangiomata.

Infantile haemangiomata are common. They may not be noticeable at birth but appear as small but rapidly growing lesions soon after birth. This rapid proliferation phase typically lasts for one to two years and is followed by a phase of involution (shrinkage) of the lesion. The most common appearance is a bright red, textured lesion on the skin but haemangioma may also occur in the mucosa and in deeper tissues. If haemangioma does not affect the skin but only deeper tissue layers, a typical bluish skin discoloration is commonly observed (Figure 1). Sometimes more than one lesion is found, with the liver being the most common location outside the head & neck region. Most infantile haemangiomata are uncomplicated, need no further interventions and can be left alone until they resolve.

About 10 % of infantile haemangiomata are more complicated, mostly because of their location, especially when the airway, oral cavity or the eye / eyelid are involved. In all these cases important functionalities (breathing, swallowing, sight) may be impacted by the growing lesion. These lesions require careful early investigations by imaging methods (ultrasound and/or MRI) as well as continued monitoring. Ultrasound Doppler imaging for the inspection of flow usually shows the lesion as a mass with a high-flow characteristic. Contrast-enhanced MRI investigations provide information about precise location and extent of the lesion(s), X-ray CT imaging only very rarely has a role in the diagnosis of haemangioma.

In most of the more complicated cases, some form of intervention will be required. When interventions are needed, this will usually be considered during the proliferation phase in order to prevent future functional impairment and/or to minimise disfigurement.

For example, haemangioma in the subglottic area (the region between the vocal cords and the windpipe) may require long-term surgical securing of the airway (tracheostomy) and later reconstructive surgery. Complications may also arise for otherwise uncomplicated haemangiomata when rapid growth leads to ulceration, bleeding or necrosis of the surrounding skin and tissues; in particular when the lower lip or ear are afflicted.

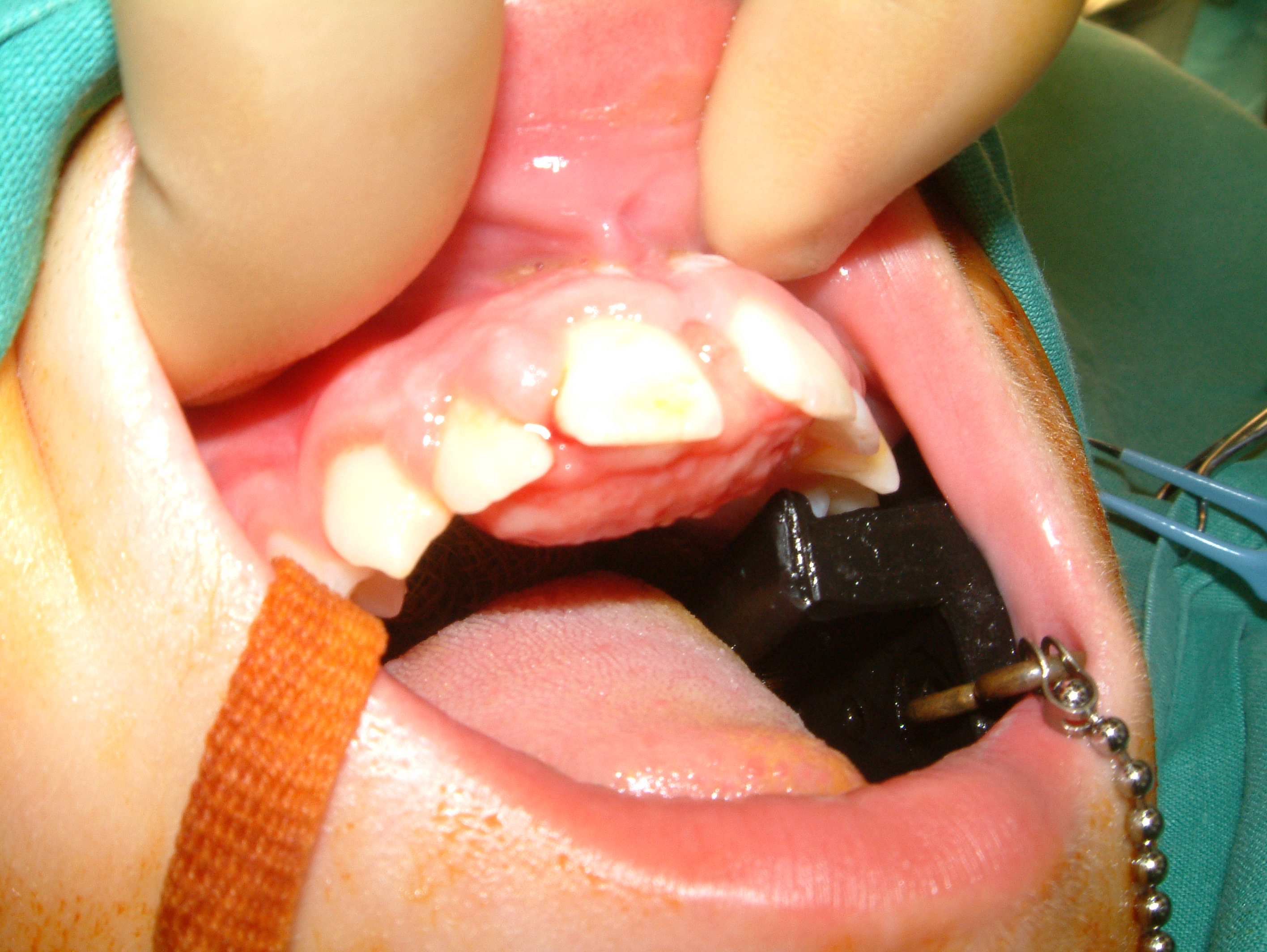

Another example of a common, benign vascular tumour that is closely related to haemangioma is pyogenic granuloma (Figure 2). Pyogenic granuloma often affects the gingiva (the gums), may cause discomfort or pain and bleeding and thus may require intervention(s).

Congenital haemangiomata, which are much rarer than infantile haemangioma, are fully developed lesions at birth and may be of significant size. They tend to occur in the same locations as infantile haemangiomas do, but are microscopically distinct from infantile haemangiomata. There are two types of congenital haemangiomata: those that rapidly involute after birth and typically will have resolved at 12 months of age; and those that do not involute (and some ‘in-between’ varieties with partial involution). Those that do not involute will show no signs of shrinkage at approximately 6 months of age and surgical interventions are often necessary. Apart from this, all other considerations for the clinical assessment / diagnosis are the same as for infantile haemangiomata.

Vascular malformations

The term vascular malformation covers a wide range of different congenital abnormalities of the vascular systems (capillaries, veins, arteries and lymphatic), and a wide range of degrees of severity of these conditions. Vascular malformations differ from haemangiomata in several regards. Vascular malformations do not resolve by themselves over time; they grow proportionately with the infant; they are always present at birth; they do not involve hyperplastic (increased numbers) endothelial cells but consist of an increasingly disturbed and dysfunctional architecture of the vessel walls. This vascular dysfunction is caused by faulty vasculogenesis (formation of endothelial cells from precursor cell in the embryo) and/or angiogenesis (sprouting of new blood vessels from existing ones). It is generally assumed that vascular malformations grow by expansion (hypertrophy) over time rather than proliferation (hyperplasy) as haemangiomata do, but there are also exceptions from this pattern. Vascular malformations may remain asymptomatic for a long time but tend to be activated by mechanical (for example, injury) or hormonal (for example, puberty or pregnancy) stimulus.

Vascular malformations can affect a single type of vessel, combinations of different types of vessels, or may occur in combination with other, non-vascular anomalies. Vascular malformations are more often associated with other syndromes than haemangioma, although these are rare conditions overall. Vascular malformations also differ in their flow characteristics. On overview of the diverse range of vascular malformations is collected in Table 1.

Table 1 An overview of vascular malformations

| Vascular system(s) * | Flow characteristics | Type / context of malformation |

|---|---|---|

| CM; capillaries | low flow | cutaneous / mucosal (‘port wine stain’); involves soft and/or hard tissue; involves central nervous system and/or optic nerve (Sturge-Weber syndrome); naevus simplex (‘stork bite’); hereditary haemorrhagic teleangiecstasia |

| LM; lymphatic system | low flow | macrocystic lymphangioma; microcystic lymphangioma; mixed cystic; generalised lymphatic anomaly; primary lymphoedema; Gorham Stout syndrome (‘vanishing bone disease’) |

| VM; venous system | low flow | common venous; glomovenous (skin; likely hereditary condition); blue rubber bleb naevus syndrome (skin and internal organs; sporadic); cutaneo-mucosal (multiple lesions affecting skin and mucosa; hereditary); Mafucci syndrome (combined with multiple hamenagiomas and enchondroma (bone marrow cyst); sporadic) |

| AVM; arterial and venous system | high flow | sporadic; hereditary haemorrhagic teleangiecstasia; forming an arteriovenous fistula |

| Combined malformations | low flow | CM + LM; LM + VM; CM + VM (+ LM) (Klippel Tréaunay syndrome; sporadic) |

| Combined malformations | high flow | CM + AVM (Parkes Weber syndrome; probably sporadic); CM + LM + AVM; CM + VM + AVM; CM + LM + VM + AVM (CLOVES syndrome); VM + AVM )Cowden syndrome, Bannayan-Riley-Ruvalcaba syndrome; PTEN hamartoma syndrome; all hereditary) |

* CM: capillary malformation; LM: lymphatic malformation; VM. Venous malformation; AVM: arterio-venous malformation

As the diverse range of vascular malformations in Table 1 suggests, severity, appearance, signs and symptoms of these conditions are equally diverse.

With increasing size, vascular malformations can cause pain, disfigurement, impaired functionalities, bleeding and infections.

Capillary malformations are arguably the least significant lesion as they are unlikely to create flow abnormalities, but can present aesthetic (‘portwine stain’) and sometimes bleeding issues.

Venous malformations are the most common vascular malformations. An example of a venous malformation of the lip is shown in Figure 3.

Clinically these lesions are classically diagnosed by pressure exsanguination (squeezing) using a transparent slide. Low-flow abnormalities may have calcifications around areas of very low flow or stagnation of blood flow, known as phleboliths (phleboliths are a useful test for students in exams when the radiographic appearance can catch the unwary, but in reality phleboliths are of little consequence).

Lymphatic malformations are a genuine puzzle in many cases. These lesions present as macrocystic and microcystic malformations. Basically macrocystic lymphangiomata are big benign cysts and can be managed as such. Microcystic lesions are problematic in that they can vary in presentation in time and place in the same person. This can create a very confusing story and can sometimes mean the story of recurrent substantial swelling of an organ (for example the tongue) is doubted. The microcystic lymphatic lesion depicted in Figure 4 could at various times be invisible, or completely block the front of this girl’s mouth.

Arteriovenous malformations are very high-flow lesions and are relatively rare. Interventional radiology is nowadays the mainstay of diagnosis, treatment planning and intervention.