Craniofacial anomalies

Contents

Treatment of malformations affecting the skull and face (and by inference the contents of those structures) requires quite rare collaboration between different surgical and other medical specialties, both simultaneously and logistically over time.

Craniosynostosis

The function of the skull (the cranium) is to protect the delicate brain tissue and expand to accommodate it as it grows (which it does rapidly in the first few months and years of life). When this role becomes counterproductive or dangerous – as in when the suture lines fuse and do not allow growth, a combination of pressure on the brain (which can be lethal) and deformity occurs.

The basis of most of paediatric craniofacial surgery is to release these fused sutures by cutting them away and allowing the brain and associated structures to grow and develop normally. The simplest procedure, a ‘strip craniectomy’ consists of simply cutting out the fused suture (most commonly the sagittal suture – the cause of scaphocephaly) without any form of reconstruction is sometimes performed by neurosurgeons in isolation. Most other fused suture resections are accompanied by repositioning of the cranial bones and reconstruction using autologous or resorbable synthetic materials.

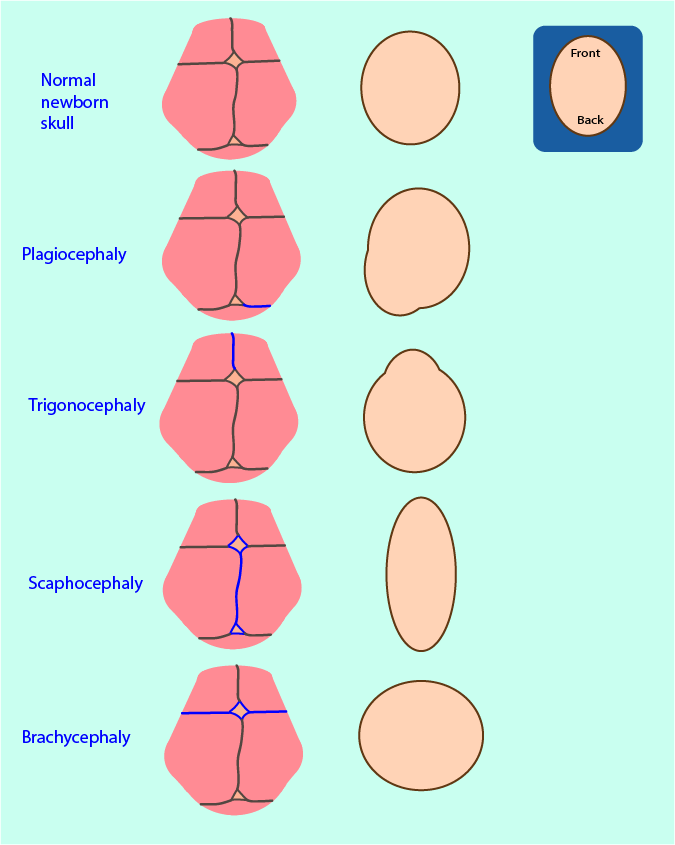

Where possible excision of the fused suture matching the deformity (Figure 1) takes place before intracranial pressure starts to increase:

- (posterior) plagiocephaly - excision of the lambdoid suture;

- trigonocephaly - excision of the metopic suture;

- scaphocephaly - excision of the sagittal suture (the most common synostosis);

- brachycephaly - excision of the coronal sutures.

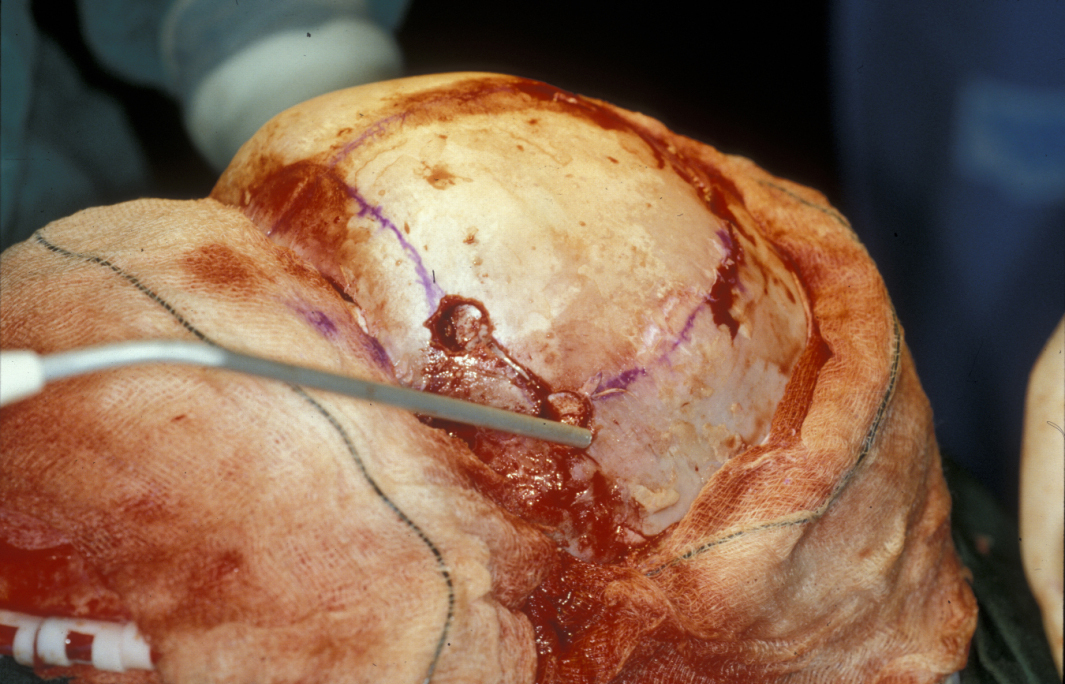

In each case surgery involves peeling back the scalp to expose the cranial bones. This is done by an incision across the skull known as a coronal flap (Figure 2). In neurosurgical circles the incision often follows the hairline. In maxillofacial circles, it tends to be further back roughly following the coronal suture, and starting and finishing in the crease in front of the ear. The area of incision is distended with saline in paediatric cases to aid haemostasis, and local anaesthetic and adrenaline solution in adults and older children. Plastic clips known as Raney clips are placed on the edges of the incision to minimise bleeding as the scalp bleeds profusely.

This exposes the periosteum covered skull and can be extended forward and downward to expose the orbital rims and zygomatic arches.

The relevant fused sutures are identified and cut out with a surgical power tool known as a craniotome, which has a blunt deep edge which lies above the dura to protect the brain while cutting skull bone.

Depending on the type of sutural fusion the relevant sutures are cut out. Reconstructive options range from none and simply allowing the expanding brain to direct growth of the surrounding skull with the removed bone being replaced by osteogenic activity, bone dust, rib grafts, resorbable plates or mesh, or surgical repositioning of bone.

Complex craniosynostoses typically occur as part of various craniofacial syndromes (see below). These conditions usually require early initial interventions such as securing the airway, combined with subsequent surgeries later in life. These may consist of a range of subcranial osteotomies and other soft-tissue surgical interventions.

In an intermediate phase both orthodontic interventions to encourage mid-facial growth using functional and hybrid orthodontic appliances, or the process of distraction osteogenesis can be used both as an alternative to, or a supplemental preparation for, orthognathic surgery.

Craniofacial microsomia

This is the second most common craniofacial anomaly, with a prevalence of approximately 1 in 5000 births. Definitive treatment may be delayed until growth is complete although hybrid orthodontic appliances are often used to encourage surrounding soft tissue growth. The degree of anatomical and physiological function of the mandibular ramus and temporomandibular joint is the determining factor for surgical reconstructive intervention.

A wide spectrum of ear and cranial nerve deformities is found. There may be mild abnormalities of the ear, or complete absence of the outer ear. Absence of the ear is more often now addressed by craniofacial implants and a semi-permanent prosthetic external ear.

Positional malformations

It is common for newborns to have a slightly strange head shape right after birth. Such minor distortions can arise from lack of space in the uterus or from the birth process. This all takes care of itself after a short while, usually within a year.

Tension or spasm in the sternocleidomastoid muscle (also known as torticollis) can create a distortion of the head shape. This develops over time, with an appearance similar to plagiocephaly or brachycephaly but in the absence of any craniosynostosis. This is known as ‘positional moulding’ or ‘deformational plagiocephaly/brachycephaly’. Treatment is to address the position of the child especially while asleep or to correct the torticollis by surgery to excise scar tissue in the distorted sternomastoid muscle and lengthen the muscle.

Treatment outlines for common craniofacial syndromes

Isolated sutural synostoses are best treated under 6 months of age by strip craniectomy and allowing normal brain growth to naturally expand the skull, thus preventing increased intracranial pressure and achieving the same skull shape as would have been expected in the absence of a craniosynostosis.

In cases where the anterior skull, particularly the naso-frontal region is involved, release of the affected suture (for example the coronal, which may be unilateral) and fronto-orbital remodelling is often recommended. This essentially involves removing, reshaping, replacing and retaining (often with resorbable plates and screws) the frontal bone.

Specific syndromic conditions:

Apert syndrome with sporadic occurrence at an incidence of around 1:100,000 the term ‘common”’ is obviously relative. The craniofacial component includes fusion of the coronal sutures and fusion of the anterior skull base and midface sutures which produces shallow orbits and hypertelorism. In addition to the craniofacial features four limb symmetric syndactylies of the hands and feet are present. Treatment is staged and individualised and should be under the care of a multidisciplinary craniofacial team as staged major and minor (remembering that no surgical intervention is really ‘minor’ to the person it is performed on) operations are required to release the coronal sutures to allow safe brain development and fronto-facial advancement to protect the eyes. Hydrocephalus requiring shunting is present in up to 10 % and isolated cleft palate is present in 30 %. Hearing deficit is more common than in the general population.

Carpenter syndrome in view of the associated congenital heart defects, intellectual challenges, hand and skull surgery may be staged. Suture excision and skull reshaping depends on the severity of raised intracranial pressure. Separation of the middle and index fingers are usually the first hand operation carried out.

Crouzon syndrome, although an autosomal dominant inheritance and affecting 1 : 25,000, has many similarities in the sutural fusions and mid-face underdevelopment to Apert syndrome (see above) and the concept of staged surgical intervention is the same. Use of local cranial bone and a range of synthetics have replaced grafts from the ribs and ilium, reducing the donor site morbidity of these already long and complex procedures on infants.

Muenke syndrome treatment is essentially similar to treatment of the other coronal suture syndromes, with the potential addition of a cochlear implant for sensorineural hearing loss.

Nager syndrome sometimes requires a tracheostomy for airway support as the initial intervention. Percutaneous gastrostomy may be needed for feeding. Later in childhood distraction osteogenesis to correct jaw underdevelopment, ear reconstruction or replacement by a craniofacial implant and a cochlear implant may be required.

Pfeiffer syndrome again usually requires coronal suture excision coupled with lambdoid and sagittal suture excision and subcranial advancement in later life, usually using external distraction osteogenesis techniques. Hydrocephalus present in type II and III Pfeiffer syndrome is shunted. Fusion of the elbow and knee joints requires expert orthopaedic input.

In Pierre Robin sequence, the airway is secured by whatever means necessary and the baby is nursed in a position to promote mandibular growth.

Seathre Chotzen syndrome usually requires excision of the involved sutures and skull re-shaping, usually early to minimise the effects of raised intracranial pressure. The ptosis can be corrected later in life if it presents an issue, and hand and foot problems may not require surgical intervention as they are often quite mild.

The maxillofacial component of Stickler syndrome is essentially cleft lip and palate surgery and possibly later maxillary orthognathic surgery, but the multiple potential other manifestations mean ophthalmic and rheumatology input is essential.

For Treacher Collins syndrome, multiple surgeries have been common in the past but intervention is best personalised to the individual patient. Early tracheostomy is sometimes needed because of mandibular retrognathism. Later mandibular reconstruction using distraction and/or bone grafting with cheekbone augmentation and external ear reconstruction or support by craniofacial prosthesis is required. Cleft palate (if present) is treated as normal.