Dysphagia

In a maxillofacial context, the majority of cases of dysphagia are managed by non-surgical means, including restorative dentistry, speech & language therapy, physiotherapy, mental health support and occupational therapy – many approaches with a major component of self-help. Speech and language therapy plays a major role in the compensatory approach to dysphagia management, by assessment and monitoring, and by swallowing rehabilitation and training. This includes a number of swallowing manoeuvres that, combined with suitable food textures, can help enable safe swallowing and oral food intake, often despite significant impairments. Speech and language therapists typically are also a good source of practical information and pragmatic ways to work around difficulties. Adaptions may include individually optimised food textures and temperatures, special cutlery, and many other useful tips & tricks, alongside developing new habits such as not talking while eating.

Surgical and non-surgical interventions

Below we give an overview of some surgical and non-surgical interventions addressing dysphagia in a maxillofacial surgery context. Some of these interventions aim to address specific symptoms of chronic dysphagia (for example, nasal regurgitation or aspiration), others aim to support non-surgical dysphagia management. Many relevant interventions are described in other sections of the website.

The role of surgical interventions in the management of dysphagia in progressive neuromuscular conditions is not well defined and is controversial. Medications used in the management of some neuromuscular degenerative conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease or myasthenia gravis (autoimmune condition leading to muscle weakness) can also mitigate related dysphagia problems, at least temporarily. Otherwise, medications play only a minor role in the management of dysphagia.

- Trismus (difficulty opening mouth) is a contributing factor to dysphagia and interventions addressing trismus can improve dysphagia.

- Placement of a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) does not address any causes of dysphagia but enables enteral (tube) feeding to maintain nutrition in the presence of severe dysphagia.

- Repair and reconstruction of cleft lip & palate and other craniofacial congenital anomalies, often in a stepwise manner over prolonged periods of time, may include periods of non-surgical management of dysphagia but eventually will resolve the underlying cause of dysphagia.

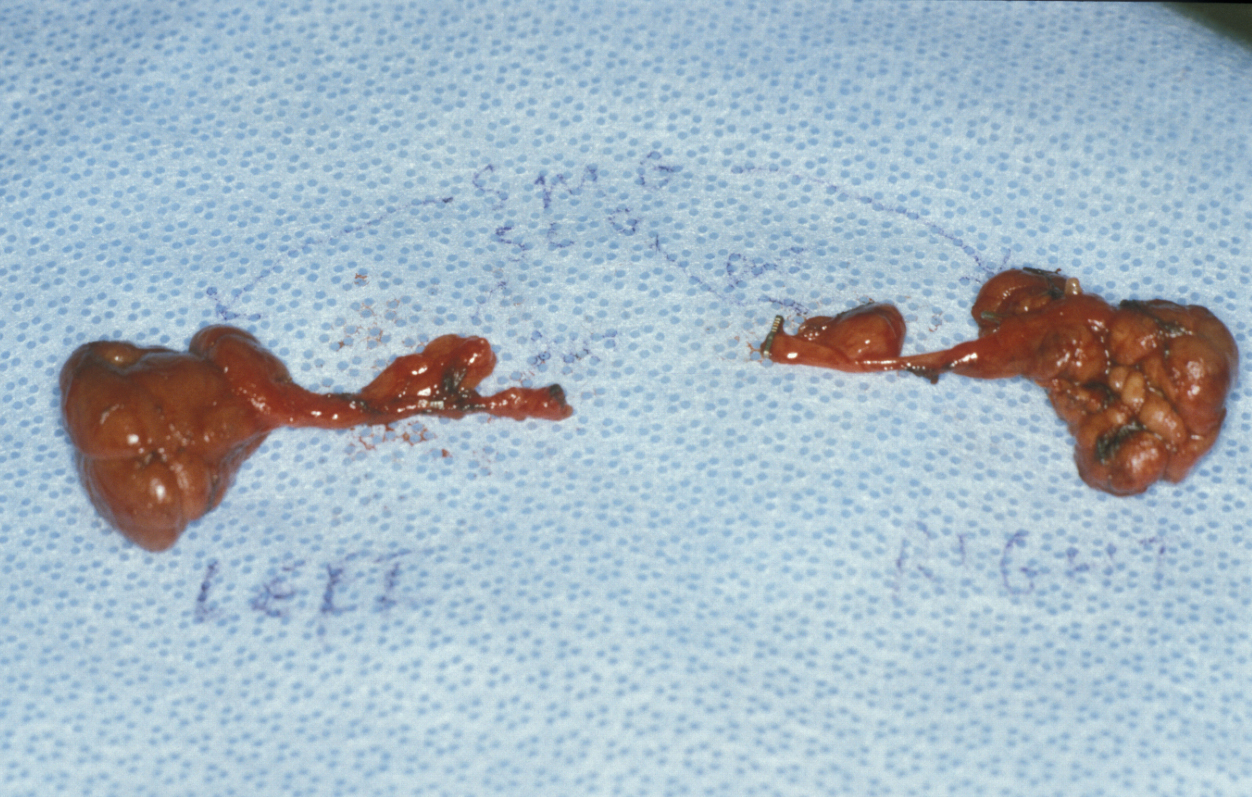

- Severe sialorrhea (drooling) is a debilitating condition, rarely resulting from hypersalivation (for example as an adverse effect of some antipsychotic medications) and more commonly as a symptom of neurological conditions. The most common cause in children is cerebral palsy; in adults Parkinson’s disease, some forms of motor neuron disease, and some forms of facial paralysis are the most common causes. Where sialorrhea is severe and persistent and giving rise to complications (such as skin infections and skin damage, combined with aspiration (see below), social dysfunction), radical interventions may be necessary. Such surgical interventions include the removal of salivary glands (Figure 1), or the relocation or ligation of salivary gland ducts. This could be excision of the submandibular, or the sublingual glands, or both. Relocation or ligation of salivary gland ducts may be targeting the submandibular, sublingual, or parotid ducts, or combinations of these. Relocation of salivary ducts, most commonly the submandibular ducts, from the mouth to the oropharynx can sometimes be a way to reduce sialorrhea problems to a more manageable level.

A slightly less radical and temporary option to manage sialorrhea can be injection of botulinum alpha toxin into the submandibular glands. This is an option if reduction of ‘resting’ salivary flow (mostly from the submandibular glands) is sufficient to reduce drooling to a manageable level.

- Aspiration, including aspiration of saliva, is a serious and potentially life-threatening complication of severe dysphagia. Relocation of salivary gland ducts does not solve this problem. Instead, surgical removal of both pairs of sublingual and submandibular glands sometimes is an effective remedy. Acute and severe aspiration may require the placement of a tracheostomy in order to protect the airway. This surgical separation of oesophagus (food pipe) and trachea (airway) is a radical solution to a serious problem and provides an option for otherwise intractable aspiration. There are different methods of placing a (long-term) tracheostomy. Placing a tracheostomy itself may cause additional dysphagia problems.

- Dysphagia as a common long-term and often severe adverse effect of radiotherapy applied to the head and neck region is usually caused by strictures or stenoses (narrowing) of the upper oesophageal region and spasms of the cricopharyngeus muscle (a circular muscle in the neck that needs to relax to allow food passage), in addition to swallowing problems associated with xerostomia (dry mouth) following radiotherapy. Endoscopic dilatation and laser ablation of pharyngeal constrictions lie within the field of ENT (ear, nose and throat) surgery (middle and lower oesophageal causes of dysphagia fall within the field of gastroenterology).

- Dysphagia related to neuropathies such as lack of sensation, is most commonly managed by adaptive and compensatory approaches and only in very rare cases benefits from surgical interventions such as nerve grafting

- Impaired tongue mobility and other similar impairments as a consequence of large oral resections and reconstructive surgery are major contributing factors to dysphagia. Most commonly, these difficulties are managed by adaptive and compensatory approaches (for example, after glossectomy and reconstruction with an insufficiently bulky free flap, it may be necessary to use a palate-lowering prosthesis to enable efficient bolus processing and transport into the pharynx) and only in very rare cases surgical intervention(s) to release constrictions may be helpful. In fact, only two practical functional reconstructions for substantial excisions of the tongue exist: enough bulk to allow posterior pharyngeal seal (a flap containing fat and skin, which tends to be retained compared to muscle which atrophies) and stretchability in areas which need to stretch for function (a flap that is thin and stretchy such as a thin vascularised skin flap).

- Dysfunction of the soft palate mostly affects speech (nasal speech resulting from insufficient closure of the pharyngeal wall from the nasal cavity) but may also be associated with dysphagia. Where the cause of the velopharyngeal insufficiency is cleft lip & palate, repair of the cleft(s) will remedy this cause of dysphagia.