Salivary gland problems

Contents

Developmental disorders and cysts

Most disorders with ectopic (extra) salivary gland tissue, such as Stafne’s bone cavity, that do not cause clinical signs do not require treatment.

The surgical treatment of cysts of the salivary glands, most commonly lymphoepithelial cysts of the parotid gland, consists of initial aspiration and cytology followed by simple extracapsular dissection (removal) if they recur.

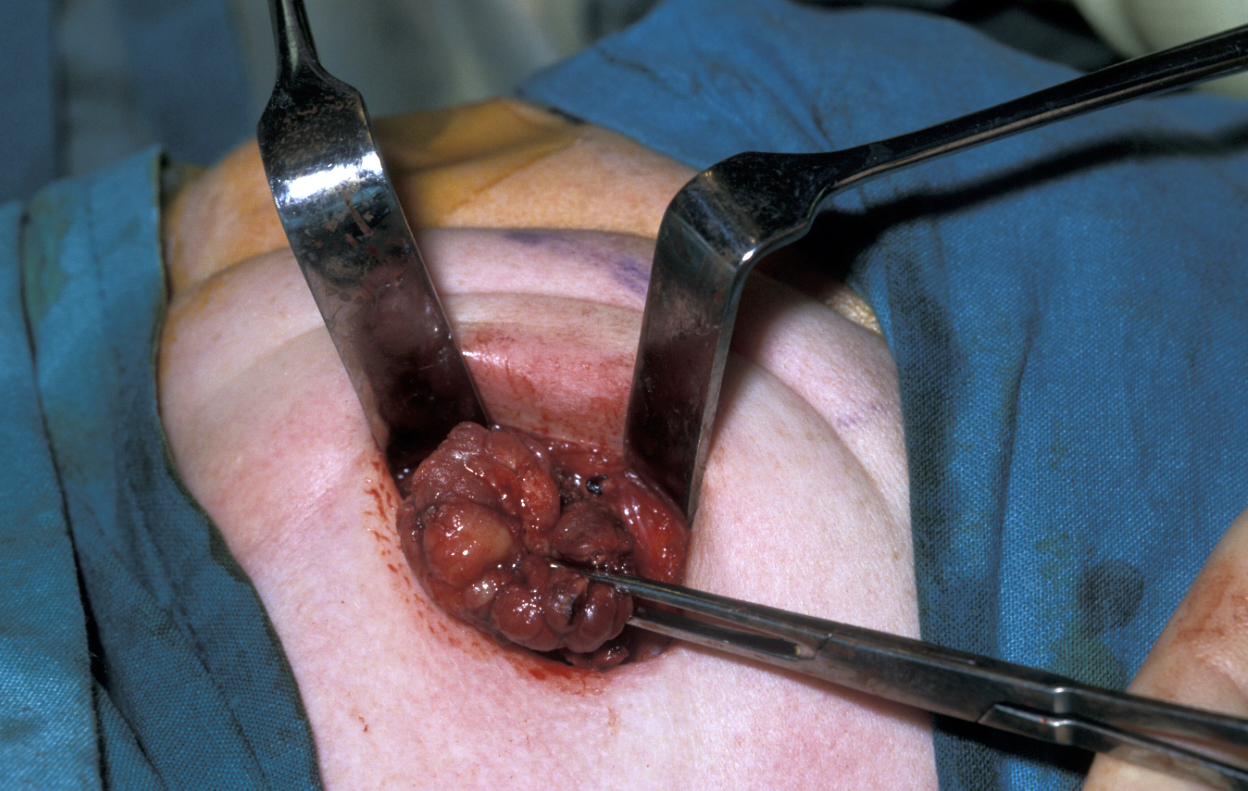

An example of a very common procedure is the excision of mucocele, a type of cyst that is associated with the minor salivary glands.

Similar to the surgical treatment of other cysts, also the surgical treatment of mucocele aims for the complete removal of the cyst. It requires adequate local analgesia, usually via bilateral mental nerve blocks. Excision is then accomplished by performing a mucosal wedge excision that avoids resecting the vermilion border (demarcation between lip and adjacent normal skin). Alternatively, the cyst itself can be dissected out submucosally. Most mucoceles are cured by mucosal wedge incision and removal of the associated damaged minor salivary glands. However, there is a small risk of recurrence.

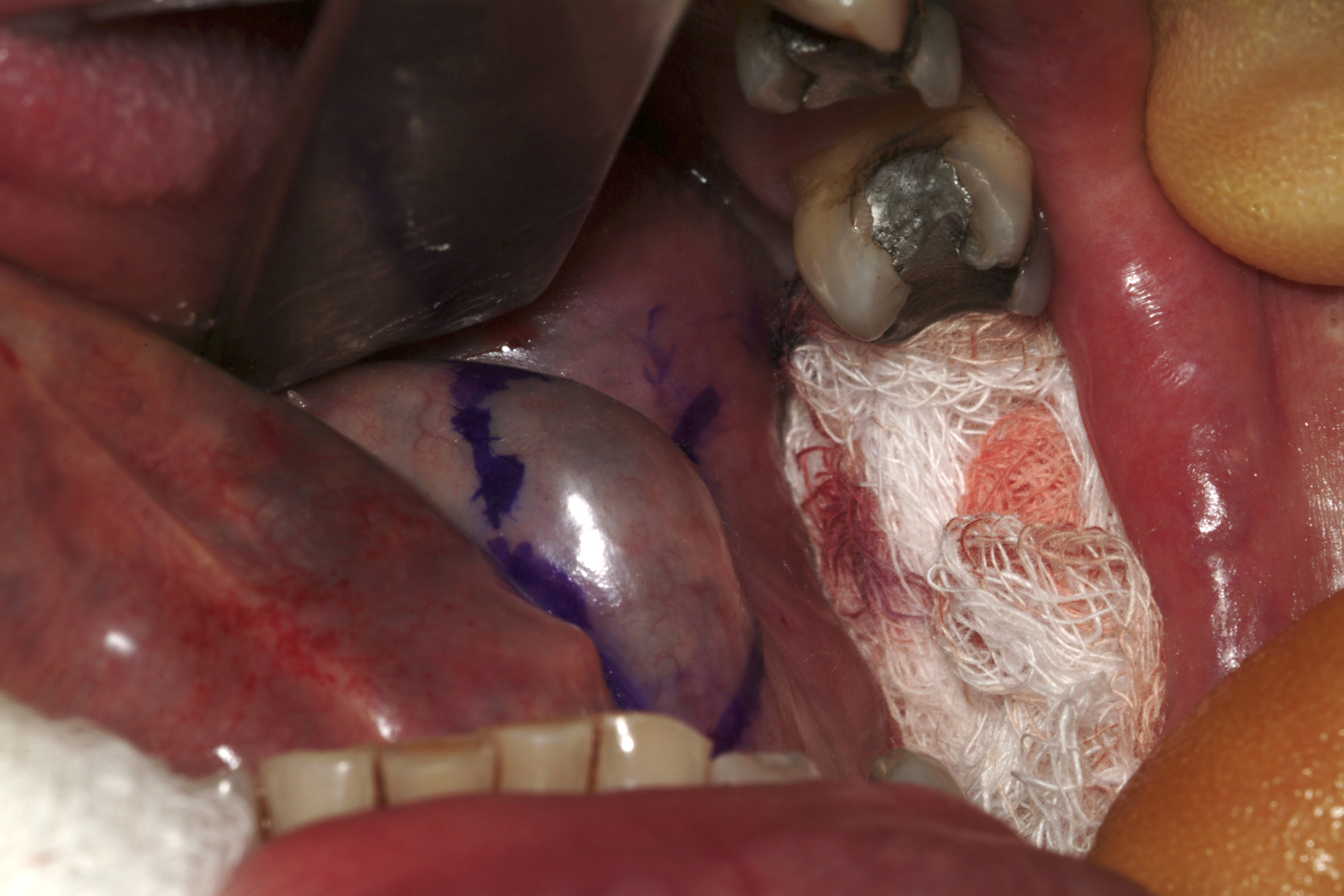

Ranula is a mucous extravasation cyst at the floor of the mouth and will reform if the associated sublingual gland is not removed (see Figure 2).

There is a risk for an altered sensation of the anterior (front) two thirds of the tongue and bleeding from the thin-walled veins that envelope the lingual nerve.

The sublingual gland lies in the anterior aspect of the floor of the mouth between the mucous membrane and the mylohyoid muscle. This gland can be difficult to approach because of the proximity of the anterior mandible (front of lower jaw). Lingual inclination of teeth (leaning toward the tongue) can make the lateral (side) aspect of the gland difficult to identify and visualise. The sublingual gland has numerous ducts and can open either directly into the overlying mucous membrane or into the terminal part of the duct of the submandibular gland.

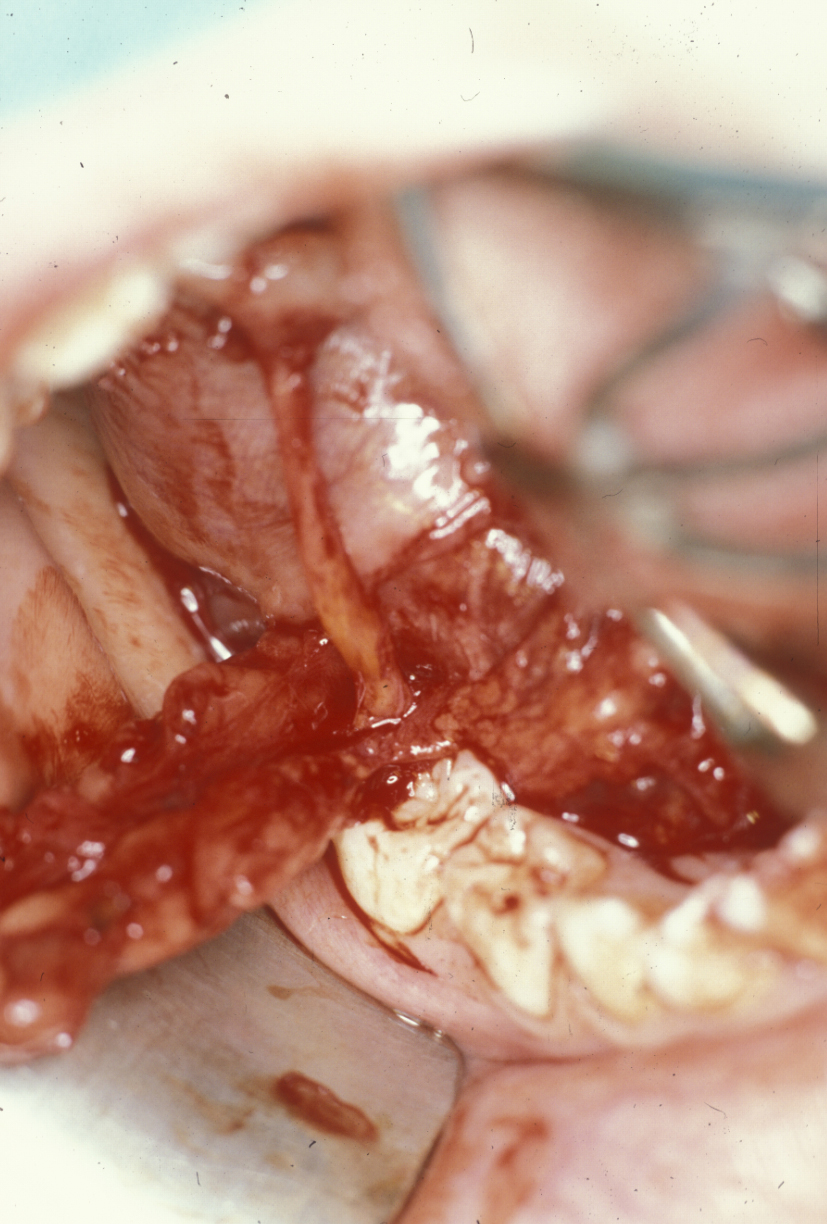

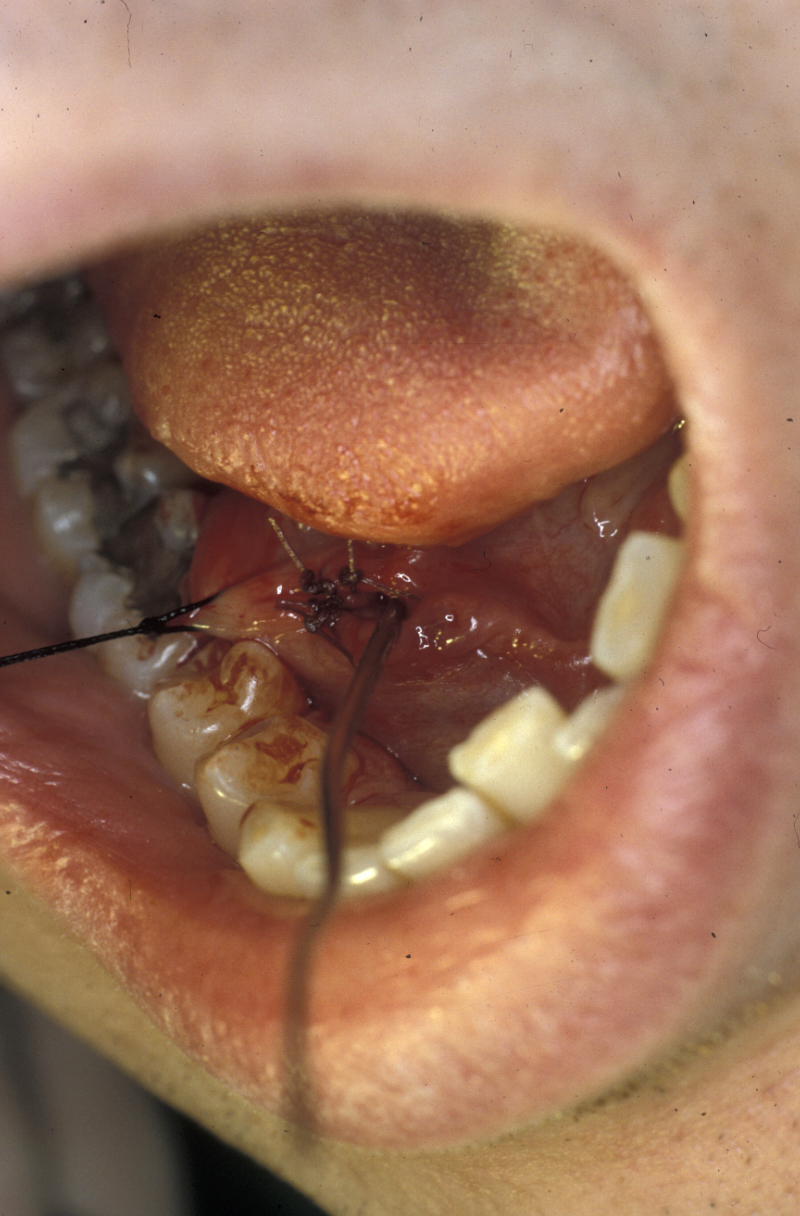

Excision of the sublingual gland is performed in conjunction with excision of the ranula, under general anaesthesia. Haemostasis (stopping bleeding) is helped by infiltrating adrenaline solution and meticulous bipolar diathermy. The position of the submandibular duct can be found by identifying its opening, and a small cuff of mucosa around the opening should be incised both to identify and to allow mobilisation of the duct (see Figure 3). This procedure retains adequate drainage for the submandibular gland, which does not need to be removed.

The intact ranula can then be dissected by a combination of scissors and swabs. The sublingual gland is identified as it envelopes the submandibular duct and is excised. The remnants of sublingual gland closest to the submandibular gland are often difficult to identify and to separate completely. It may be necessary to leave small remnants of sublingual gland tissue in the area. Obvious residual sublingual gland tissue should be cauterised to minimise leakage of saliva. Adequate haemostasis should be ensured at this point because postoperative bleeding can be a real problem.

Furthermore, excision of both sublingual glands is the most common treatment for severe cases of drooling: the two sublingual glands are removed and the submandibular ducts are redirected so that saliva from the submandibular glands is emptied into the oropharynx (rather than the mouth). Careful preoperative assessment is required as not all patients may be suitable. This treatment does not usually eliminate the problem completely but reduces it such that it becomes more manageable (less frequent bib changes). Applying botulinum alpha toxin directly into the submandibular gland can provide a temporary solution if reduction of ‘resting’ salivary flow (that is – when not eating; usually from the submandibular glands) is helpful. Aspiration of saliva can be a serious complication of severe dysphagia. This problem is not helped by duct transposition of the submandibular gland and the old-fashioned, but effective, remedy of bilateral sublingual and submandibular gland excision is more helpful in that case.

Obstructive disease

The ductal system of the major salivary glands may be blocked by calculi (stones), mucus (thick secretions) or strictures (narrowing or other limitations).

Obstructive disease, mostly affecting the ducts of the submandibular gland may be acute or chronic. In either case, there may be a swollen gland with bacterial infection, mandating treatment with antibacterial medication, typically a penicillin, which is sometimes needed intravenously. An acute obstructive condition may be painful and require analgesia. After an acute episode, removal of the calculus or the submandibular gland is required. It is often the case that the submandibular gland will have suffered irreversible damage and requires removal following a severe infection. Chronic obstruction of the submandibular gland can result in a fibrosed (irreversibly scarred) gland and also requires removal of the gland (see below).

The parotid gland survives acute infective episodes better than the submandibular gland. Removal of the obstruction in a parotid gland usually results in recovery of normal function. Typically, a sudden bad, often salty, taste in the mouth will be related to quite sudden relief of symptoms.

Calculi of the salivary glands may be dealt with in several ways. In the submandibular gland, if the calculus is visible in the duct on an X-ray radiograph and is relatively anterior (to the front) and palpable, it may be removed using local anaesthesia in a procedure called transoral sialolithotomy. The area is infiltrated with a local anaesthetic agent, and a stay suture is placed beneath the duct proximal (near) to the palpable calculus (see Figure 4).

Traction is applied to the suture to tent up the tissues, and it also prevents the calculus from moving backward toward the gland (in fact, fibrosis around calculi and their irregular shape mean that they often do not move). A longitudinal incision is made over the calculus, thus exposing it. It can now be teased out of the duct. Mucosal (lining tissue) closure is all that is needed; stenting the duct or duct repair does not improve the outcome. Anterior defects should be left open because this produces a wider meatus (canal-like opening). Parotid calculi may be dealt with in a similar fashion. In either case the papilla (projection of the opening of the duct into the mouth) should not be incised as this may form a stricture.

If a calculus is very proximal in the duct at the junction of the duct and gland, or within the gland, removal of the gland is usually indicated (see below).

In certain cases calculi are amenable to other treatment options such as a basket retrieval (using a device that allows capture and ‘fishing’ out the calculus) or lithotripsy (a treatment where typically ultrasound shocks are used to fragment a calculus such that it can be shed naturally, a well-established treatment modality in particular for kidney stones). Strictures may be treatable with balloon dilation. Sialoendoscopy and other minimally invasive procedures have become popular in some areas but have yet to gain widespread acceptance.

Infections

Acute bacterial sialadenitis (inflammation of a salivary gland)

This condition usually affects the parotid gland. Initial treatment involves antibacterial agents, rehydration and analgesia. Sialogogues (substances that promote salivary flow) such as simple lemon drops may be used. If an abscess has formed incision and drainage may be required. However, abscess formation is a rare complication, and incision and drainage should be avoided if possible because of inevitable damage to the parotid gland. This damage may create a salivary fistula which can then necessitate excision of the parotid gland (see below).

Following recovery from the acute phase a sialogram will be required to investigate any underlying abnormality and often this investigation is therapeutic due to the mechanical irrigation with an antiseptic (the contrast agent usually contains iodine).

Chronic sialadenitis and submandibular gland excision

This inflammatory condition tends to affect the submandibular glands (probably due to the more viscous secretion being more difficult to clear than that of the parotid gland, and the propensity for calculi to form in the submandibular duct). Chronic bacterial sialadenitis usually occurs in a gland that has had a history of an acute infective or obstructive episode.

Treatment is by removal of the offending gland. In the case of the parotid gland, a ‘total’ parotidectomy (see below) with facial nerve sparing and ligation of the duct will eradicate most cases. This involves morselisation (breaking up into small pieces) of the gland around the facial nerve and removal of the vast majority of saliva producing acini (secreting cells). Some surgeons attempt duct ligation alone, usually with some method of suppressing saliva production (for example propantheline and/or nasogastric feeding). The hope with this method is that the gland will undergo atrophy (will waste away). This often makes for a very unpleasant initial few weeks and the overall long-term success is questionable.

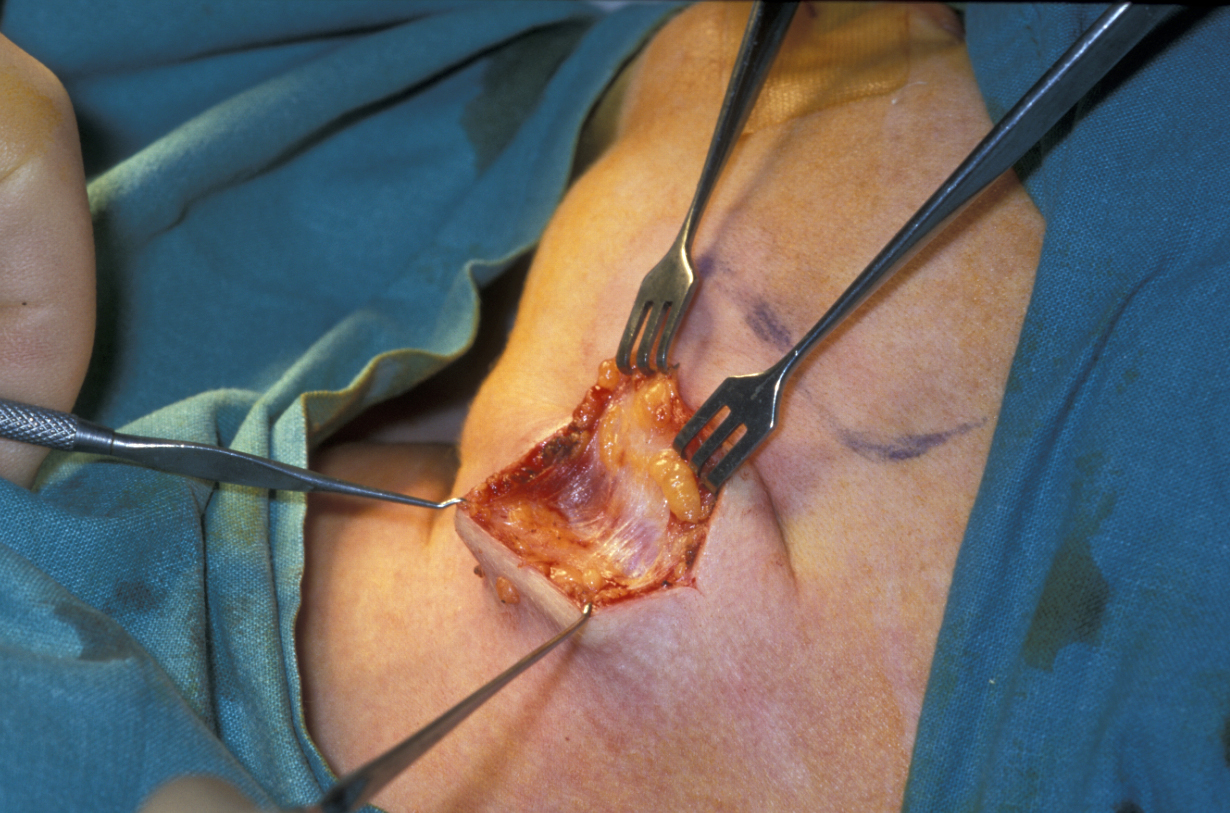

Submandibular gland excision is required after the gland has suffered irreparable damage from infection and/or obstructive disease. The surgical approach is by trans-cervical (from the neck) approach. The incision is two finger-breadths below the lower border of the mandible. A 3 to 4 cm incision is made. The incision is then deepened through fat that bleeds; bleeding needs to be controlled using bipolar diathermy to expose the platysma muscle (a broad sheet of muscle covering front and sides of the neck; see Figure 5).

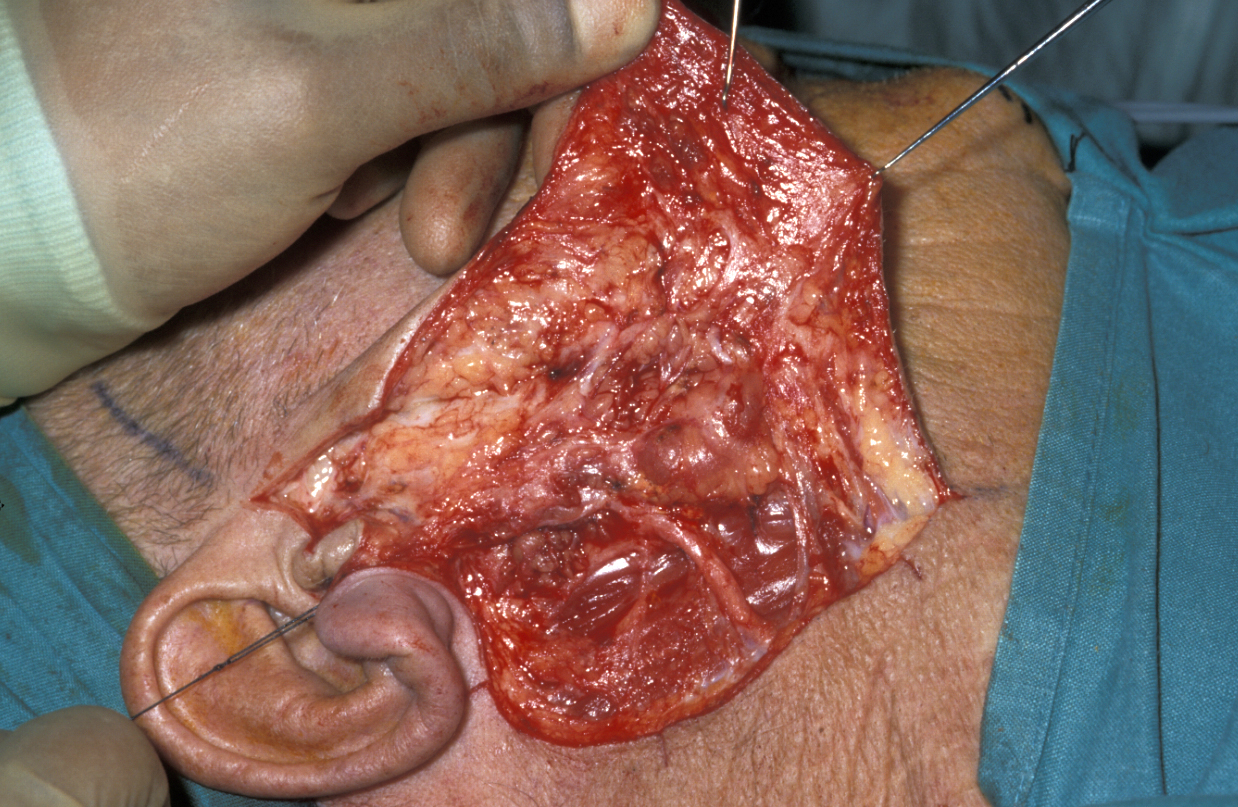

Platysma is divided and the lower border of the submandibular gland identified, enveloped in the submandibular fascia. The fascia is incised and an upper flap developed. The flap includes submandibular fascia, platysma, fat and skin. This approach and adhering to the gland will preserve the function of the marginal mandibular branch of the facial nerve. The superficial pole of the gland is mobilised posteriorly (on the back; see Figure 6), if need be by ligating the facial vessels (but this is not always needed), anteriorly by counter-traction and inferiorly by finger dissection.

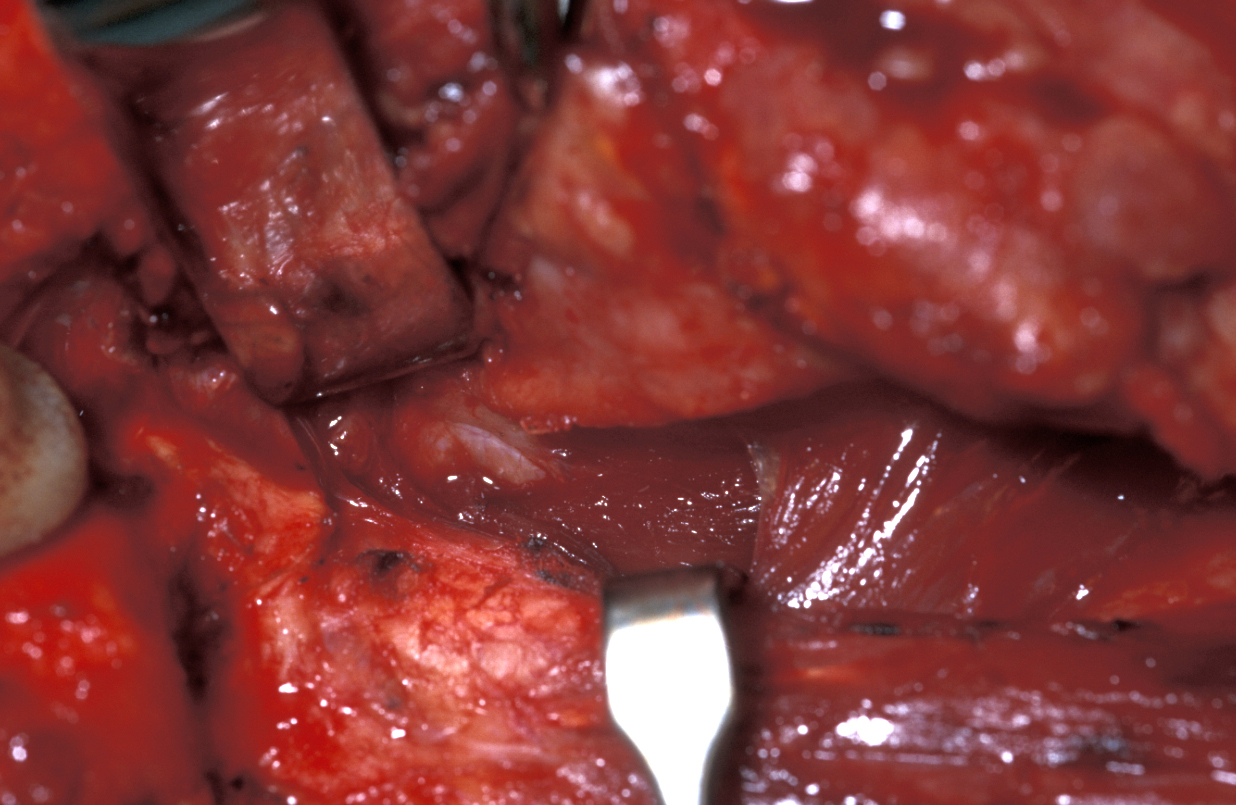

The mylohyoid muscle (a pair of muscles running along the front of the neck from the floor of the mouth downward) is then retracted and the gland placed on traction. Finger dissection usually frees the gland up and the lingual nerve (in the floor of the mouth) is pulled down by counter-traction, exposing the submandibular ganglion (part of the involuntary nerve system of the head & neck region) and the associated thin walled veins. The ganglion should undergo bipolar haemostasis and then is dissected free. This allows the lingual nerve to spring free, and the gland will be adherent by a few fascial attachments and the submandibular duct. The submandibular duct should be traced as far forward on the floor of the mouth as possible, ligated and divided. Bipolar haemostasis is carried out, the defect has a drain placed and is closed in two layers.

Sjögren’s syndrome

Sjögren’s syndrome is an autoimmune disease characterised by a dry mouth (xerostomia) and dry eyes. There is no cure for it and the management of Sjögren’s syndrome is largely directed toward symptom control. Involvement of a rheumatologist and ophthalmologist will often be required. There are some tried and tested strategies to find relief of the symptoms of xerostomia but not all of these work for everybody.

The decreased salivary flow increases the risk of caries and mandates meticulous oral hygiene, regular dental attendance and fluoride supplements. All patients with xerostomia are at higher risk of oral fungal infection, candidiasis. This tends to exacerbate the discomfort and should be treated aggressively (often a higher dose of fluconazole than normal, possibly with additional miconazole in recalcitrant cases as there will be a small number of cases of fluconazole-resistant candida). The lack of tears is treated with methylcellulose eye drops. An increased risk of lymphoma formation should be borne in mind, especially if a lump develops in the parotid glands.

Salivary neoplasms – benign tumours

There is a huge and bewildering range of salivary neoplasms as described at length in the section dealing with diagnoses of salivary gland conditions. The most common of these neoplasms, pleomorphic salivary adenoma, in the majority of cases occurs in the parotid gland, and there it usually occurs in the superficial lobe of the gland. Although benign, the pleomorphic salivary adenoma is poorly encapsulated and requires excision with a small margin of normal tissue.

Therefore, superficial or total conservative parotidectomy (see below) has been the standard of care for many years. More recently the use of magnification and the technique of ‘extracapsular dissection’ has become popular at the ultraconservative end of surgical treatment strategies. A more common approach is the selective superficial parotidectomy, where only the branches of the facial nerve above and below the tumour are dissected. A segment of tumour and normal parotid is excised under direct visual control of the facial nerve and a greater or smaller portion of normal gland is left in place. There can be significant mucus-filled cystic areas to these tumours and these must be handled carefully at surgery as any spillage can produce recurrence. Recurrence of pleomorphic salivary adenoma is often multifocal and very difficult to treat, with options ranging from total parotidectomy with radiotherapy to isolated removal of recurrence, depending on individual circumstance.

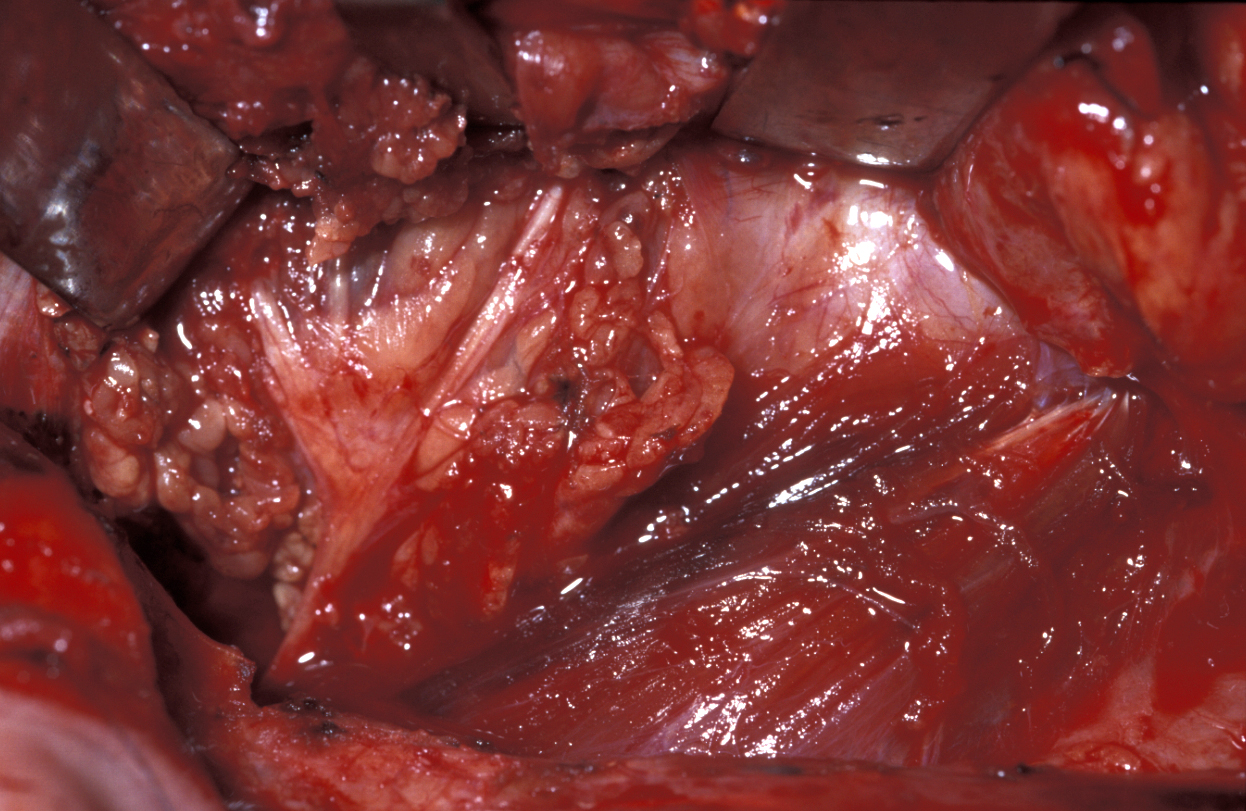

Another location where salivary gland pleomorphic adenoma may occur is in the palate area, most often at the junction of hard and soft palates (see Figure 7).

For all tumours which overlay the hard palate, simple subperiosteal excision with a mucosal margin is adequate (see Figure 8). Healing by secondary intention (leaving the wound as is) of the palate is excellent and can be achieved by using a dressing plate with a sedative and soothing dressing. If the tumour extends into the soft palate, the capsule of the tumour can be elevated from the underlying levator aponeurosis (a thin structure that connects the levator muscle (the muscle responsible for lifting up the soft palate when saying ‘ahhh’) . The soft palate defect will granulate with good functional result. If the levator aponeurosis is breached, however, this has to be repaired and should be reconstituted with vascularised tissue, such as a buccal fat pad flap, or a temporoparietal fascial flap.

Parotidectomy

There are different versions of parotidectomy, the removal of the parotid gland (or parts of it). Parotidectomy is divided into extracapsular dissection, (so called) superficial parotidectomy, deep lobe parotidectomy, total facial nerve preserving parotidectomy, and radical parotidectomy in which the facial nerve is sacrificed. Any facial nerve-preserving parotidectomy is basically a dissection of the facial nerve.

The vast majority of parotidectomies are approached via a cervical (neck) mastoid (bone behind the earlobe) facial incision, starting in the preauricular sulcus (groove in front of the ear), looping underneath the earlobe around the mastoid and down into a neck skin crease. A skin flap is raised over the parotid fascia and the skin overlying the sternomastoid; this is elevated forward on a very similar plane to a cutaneous face lift. The parotid fascia is identified, the great auricular nerve is identified and the posterior branch preserved where at all possible (see Figure 9).

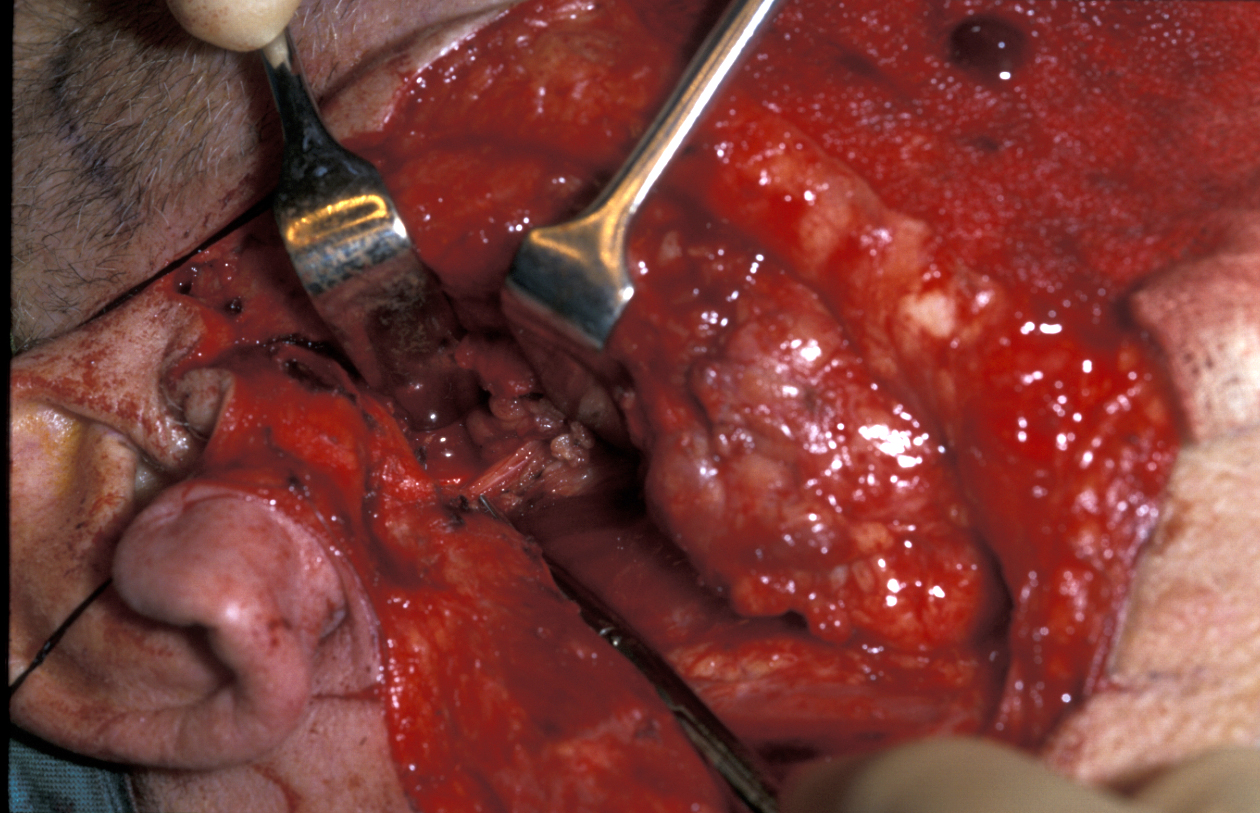

The groove between the parotid gland and the sternomastoid muscle (long muscle in the neck from behind the ear to where the right and left collarbones meet) is developed to identify the posterior belly of the digastric muscle (pair of muscles under the jaw, involved in jaw movement) as shown in Figure 10.

This is the depth at which the facial nerve will be found. The preauricular incision is deepened in a relatively avascular (few blood vessels) plane between the auricular (ear) cartilage and the parotid gland. This leads down to the inferior portion of the cartilaginous canal of the external auditory meatus that points in the general direction of the facial nerve, 1 cm deep and inferior to its tip. The facial nerve will lie in the area indicated by the so called cartilaginous pointer at the depth of the posterior belly of the digastric muscle (see Figure 11).

The remaining attached parotid gland can therefore be proceeded through quite quickly.

A further method to localise the facial nerve is to identify the groove between the cartilaginous and bony external auditory meatus because its sharp lateral edge of bone will be felt. It lies immediately superficial and superior to the nerve at its point of exit from the skull, and it is a good fall-back position if the nerve has not already been identified.

Once the facial nerve is identified the dissection should take place along the plane of the nerve lying just superficial to it (see Figure 12).

The next stage of the procedure will vary depending on whether tumour or sialadenitis is the indication:

- sialadenitis: morcelisation (fragmenting) of the gland lateral to the nerve is the quickest and the most effective way to remove it;

- tumour: the nerve branch is identified above and below the tumour so adequate excision can be carried out.

When the tumour is confined to the deep lobe of the gland (medial to the facial nerve and usually behind the posterior border of the ramus of the mandible), it may be necessary to osteotomise (cut) the ramus (vertical part of the jaw bone) and mobilise the segments to allow adequate three-dimensional access for safe excision of the tumour (see Figure 13).

A certain capacity to deal with the unexpected is an important asset in salivary gland surgery. Pure deep lobe tumours identified on imaging may be best approached using a labiomandibulotomy (splitting of the lip and mandible) approach along the floor of the mouth. The swinging out of the mandible provides excellent three-dimensional access to the lateral pharynx (throat). Another approach is purely from below but by dividing the digastric muscle.

Some surgeons will only carry out parotid surgery with a facial nerve monitor in constant use. Others find this an unwelcome distraction. Many will confirm the facial nerve trunk is functioning at the beginning and end of the operation using a facial nerve stimulator. Closure is with a drain and two-layered closure.