Swallow

The many causes of dysphagia affecting the oral and oropharyngeal space include degenerative conditions (such as motor neuron disease, myasthenia gravis, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease), neurological conditions (such as cerebral palsy, dementia, stroke, fetal alcohol syndrome) and genetic disorders (such as Down syndrome, Rett syndrome). The assessment and management of dysphagia related to these conditions is not discussed here.

Our discussion of swallowing assessments and nonsurgical management concentrates on dysphagia related to maxillofacial conditions, in particular

- head & neck malignancies, at all stages of disease and treatment;

- major trauma;

- cleft lip and palate;

- craniofacial syndromes and some facial disharmony surgery.

Dysphagia management for most of these conditions needs to be seen in conjunction with surgical interventions and other treatment modalities, such as radiotherapy, addressing these underlying condition(s). It is important to remember that not only are there many different forms of dysphagia, but generally dysphagia affects different people, even with very similar conditions, in different ways. Relevant impairments of the swallowing process include reduced lip seal, reduced tongue motility, delayed swallowing reflex, reduced elevation of the soft palate, reduced larynx elevation, reduced movement of the epiglottis and/or hyoid, severe xerostomia, trismus, reduced jaw movements – and combinations of swallowing impairments. Hence, our pages can only give a general overview with some examples included, and highlighting the need for individual assessment and support.

Some general remarks

The procedures related to assessment and non-surgical management of swallowing problems vary, depending on the underlying problem. Obviously, the situation for an infant with cleft lip & palate is different from the situation of an adult following major maxillofacial surgery and/or radiotherapy applied to the head & neck region.

Nevertheless, the overarching theme to swallowing assessment is to establish the ability, efficiency, and above all the safety of swallowing. The time it takes for somebody to complete a single swallow is a crude measure of the efficiency of swallowing. The ability to swallow is correlated with the degrees of independence from tube feeding in order to provide somebody with all their daily nutritional needs by mouth. The safety of swallowing is related to the presence/absence of aspiration and pooling of residual food and/or saliva.

These various criteria taken together inform recommendations for the respective optimum management of dysphagia. These strategies can (and do) vary widely and may change considerably over time, with some dysphagia conditions likely to improve over time, and others having a tendency to get worse. Recent studies highlight unmet needs of many head & neck cancer patients for better pre-treatment information about expected swallowing and speech outcomes. Some other studies suggest that swallowing therapy within one year of completion of radiotherapy delivers the most consistent improvements when compared with a later start of swallowing therapy.

Swallowing assessments

A comprehensive assessment of dysphagia includes instrumental (‘objective’) and non-instrumental (‘subjective’) components contributing to the overall assessment of the signs & symptoms of someone’s dysphagia. Medical history and medical examination(s) are the starting point, in particular oral examinations (for example, observation of salivary flow or examination of sensation) and assessment of airway protection, coughing reflex & strength. Somebody’s subjective accounts of their swallowing problems are important, and need to be combined with instrumental and non-instrumental observations in order to form a comprehensive picture. This is a collaborative effort between speech and language therapist and patient.

Assessing the swallowing process typically involves a series of a standard range of food textures offered, and the associated swallowing performance being recorded. This is done both from simple observation and by fibre-optic endoscopic examination, and sometimes complemented by additional ‘barium swallow’ investigations. Fibre-optic examinations sometimes employ test food preparations that are coloured by dye to improve observation.

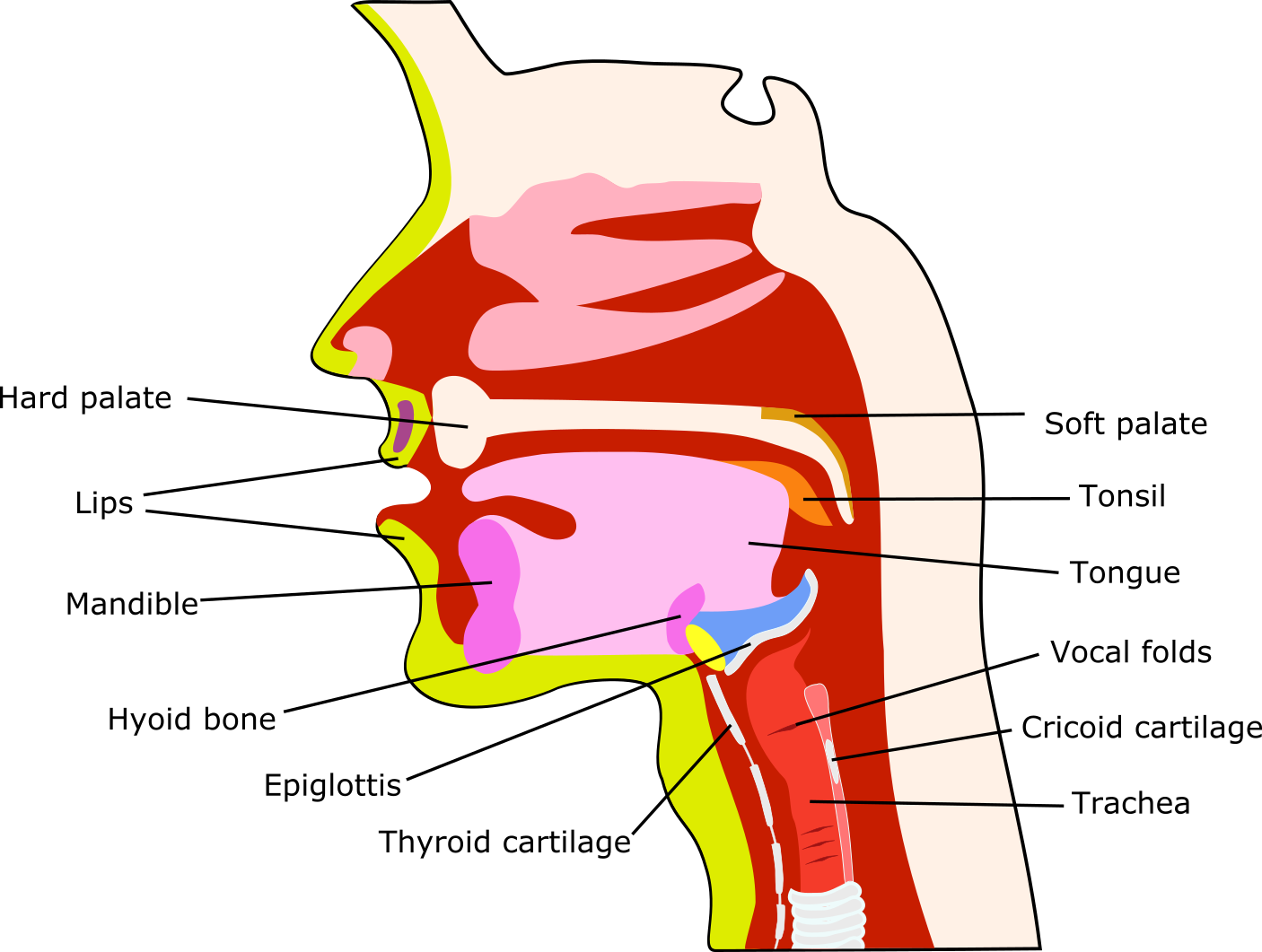

In these multiple ways, a comprehensive picture about lip seal, tongue mobility & control, bolus manipulation, food and/or saliva residues, swallowing and coughing reflexes, soft palate motility, airway protection can be obtained. Figure 1 is a sketch of the many structures actively involved in the mechanical aspects of swallowing. This is further illustrated in Figure 2 and Figure 3, where real-time MRI videos of swallowing in healthy volunteers show swallowing of carrot puree, and an ‘empty’ swallow, respectively.

Recommendations based on swallowing assessments

Recommendations resulting from swallowing assessments, generally speaking cover the whole spectrum from ‘nil by mouth’, to a tailored list of interventions, to ‘no interventions required’.

Tube feeding may be recommended as the sole feeding method or to supplement insufficient oral food intake and/or to prevent aspiration, on a short- or long-term basis. Enteral feeding is the recommendation when all else has failed and there is no other option to maintain nutrition and hydration orally.

Many swallowing problems can be managed successfully by a combination of various adaptive and compensatory strategies. Adaptive approaches include the use of tools such as special spoons (for example, to deliver food directly to the back of the mouth), drinking straws, special bottles and/or bottles with special nipples (for example, to feed infants with cleft lip & palate), prosthesis, such as palatal drop prostheses or obturators. Obturators are individually designed to fill in a maxillary defect after resection, so that the oral cavity is sealed from the nasal cavity. Palatal drop prostheses (sometimes in combination with an obturator) help to make contact between the palate and a partially resected, or reconstructed tongue so that it is possible to clear a bolus from the mouth into the pharynx.

The choice of suitable and safe food textures is an important aspect of adaptive strategies. These choices, depending on the specific dysphagia, could be anything from a liquid diet, through soft and smooth food textures, all the way to diets avoiding liquids and instead using thickened fluids or jellies. Recommendations may also include the effects of food temperature on swallowing efficiency (varied food temperature, taste and temperature, increase sensory awareness in the oral cavity), and suggestions about optimal bolus size and placement in the mouth. For many maxillofacial patients with dysphagia, food choices are part of an overall strategy that includes compensatory methods (such as special swallowing manoeuvres, see below). Sometimes there is some individual choice whether somebody prefers to eat texture- and temperature-adapted foods with little attention to special swallowing techniques, or if it is preferable to employ special swallowing techniques and in this way have fewer restrictions with regard to safe food consistencies and textures (such as being able to swallow liquids safely).

Compensatory approaches are mostly special swallowing manoeuvres (see below) as well as a range of swallowing exercises (see below). Compensatory methods have to be used consistently to assure safe eating, they form part of somebody’s ‘new normal’.

Special swallowing manoeuvres

There are a number of techniques aiming to improve safety and efficiency of impaired swallowing. Some techniques simply exploit posture to improve flow & control of the bolus, and eliminate or reduce aspiration. Other techniques are modifications of the normal swallowing process.

Exploiting posture

Adopting particular postures of head and/or body can be efficient and straightforward ways to reduce, or even eliminate aspiration and to improve bolus transport. These specific postures work well for the majority of people, and it is straightforward to learn how to exploit postures for safe(r) swallowing. It has been reported that many people prefer postures over having to rely on, for example, thickened liquids.

- Chin tuck (or chin down) – involves touching the neck with the chin during swallowing. This posture is helpful to compensate reduced tongue base retraction, reduced elevation of the larynx, and delayed pharyngeal phase of swallowing. The posture narrows the opening of the airway and thus improves airway protection and can eliminate aspiration.

- Head back – involves leaning the head back during swallowing. This posture exploits gravity to help shift the bolus from the oral cavity to the pharynx. It is not suitable when there are additional issues with airway protection.

- Head rotation – involves rotating the head toward the weak side. This posture helps to direct the bolus transport via the stronger / normal side. It increases the opening of the upper oesophageal sphincter (‘valve’ at the top of the oesophagus) and reduces its pressure. It is a suitable posture to reduce aspiration for people with unilateral weakness of the pharyngeal wall.

- Head tilt – involves tilting the head toward the stronger/normal side. This posture exploits gravity to shift the bolus via the stronger side. It is useful for dealing with unilateral oral and pharyngeal weakness.

These postures can be used on their own, or in combination with other postures and swallowing manoeuvres (see below). Our physiotherapy pages demonstrate these postures in videos as general exercises to strengthen the neck muscles.

Swallowing manoeuvres

These swallowing techniques are intended to ‘take (voluntary) control’ over parts of the oropharyngeal swallowing phase. These techniques typically require a little more training & practice to learn how to perform them properly. Once mastered, these techniques help reducing aspiration and improving swallow efficiency.

- Supraglottic swallow (and super-supraglottic swallow) – involves airway protection during swallowing under voluntary control. This is achieved by taking a deep breath, holding the breath (this closes the vocal folds in the larynx) while swallowing, and coughing immediately after the swallow. The super-supraglottic swallow is a slightly more energetic and effortful variant of the technique. Both manoeuvres are designed to protect the airway by closing the vocal folds well ahead of the bolus arriving once the swallow is started. For some people with a sufficient coughing reflex and coughing strength, the voluntary post-swallow coughing can be omitted.

- Effortful swallow – involves improved movement of the posterior tongue base in order to propel the bolus along its way. This is achieved by pressing the tongue against the hard palate while swallowing.

- Mendelsohn manoeuvre – involves enhanced opening of the oesophagus in order to accelerate and ease passage of food and drink. It is one of the techniques aiming to protect the airway, and it reduces food residues in the pharynx. This is achieved by voluntarily prolonging the elevation period of the larynx during swallowing. It takes some practice to learn how to extend the laryngeal elevation with the help of some of the throat muscles. It can be practised without food initially. The manoeuvre is a useful strategy to improve a range of swallowing problems, including a delayed and poorly coordinated swallowing process, reduced range of movement of the larynx, and poor bolus transport. The Mendelsohn manoeuvre is also a useful swallowing exercise (see below).

- Tongue hold – involves enhanced movement of the posterior wall of the pharynx for better bolus transport to the pharynx. This is achieved by sticking the tongue out and holding it between the front teeth during swallowing. The technique needs careful individual assessment because it can lead to increased residues in the pharynx (because it delays the pharyngeal swallowing reflex) and thus can increase the aspiration risk. Therefore, the technique is more commonly used as a swallowing exercise (see below) rather than a support technique for swallowing food.

Alongside practical instructions and support in learning postures and special swallowing techniques, the resulting reassurance and generally supportive role of speech and language therapy (‘practical psychology’) gives most people the confidence to try at home and recover much of their oral food intake competence in time. Some people may be very anxious and still lack confidence to manage on their own; in such cases further interventions such as counselling or other psychological interventions may be helpful in supporting the recovery process.

Swallowing exercises

Swallowing exercises may be seen as a particular form of physiotherapy. In this regard, swallowing exercises differ slightly from swallowing manoeuvres. The latter are means to manage and mitigate some swallowing impairment, whereas swallowing exercises aim to rehabilitate swallowing ability, efficiency and safety as much as possible (for example, exercises to prevent or improve trismus are demonstrated in videos on our pages about physiotherapy). There is considerable overlap between these two categories.

The merits of swallowing exercises in general are not questioned. However, occasionally there seem to be some motivational barriers with some people to persevere with such exercises. It is debated, though, if prophylactic swallowing exercises have a long-term benefit for head & neck cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy (which, again, may be related to poor engagement) or if similar / identical long-term outcomes are achieved with a later start of swallowing exercises.

Swallowing exercises are meant to improve / rehabilitate swallowing over time, aiming to reduce in the longer term restrictions on oral food and the need for special swallowing manoeuvres – in short, the aim is to return swallowing and oral food intake functions to normal as far as is possible (but patience and perseverance are necessary). This is an important goal in that this is closely related to quality of life, as widely reported by patients and carers. Broadly, swallowing exercises can be subdivided into subgroups aiming to improve bolus manipulation, movements of tongue & jaws, tongue strength, airway protection.

Mouth opening is an obvious necessity in order to enjoy oral food intake. Trismus, difficulties with mouth opening (technically with jaw opening), can be improved by a range of exercises, some of which are demonstrated in videos on our physiotherapy pages.

Exercises to improve bolus manipulation

Essentially, these are exercises aiming to improve the mobility of the tongue specifically with a view to better manipulation of a bolus. Most of this can be practised in various different ways, using a lollipop or a small piece of marshmallow, or a small piece of gauze soaked in the preferred drink (to help with motivation (if safe to swallow liquid)…), or similar ‘objects’. Such exercises may indirectly also help to identify the optimal size and texture of the bolus that person can swallow.

- Lateral tongue movement – practices moving a bolus / ‘object’ to different locations in the oral cavity, from tongue to back of teeth and gums. Initial practising with gauze or a lollipop is safest as one can hold on to the object and there is no danger of accidentally swallowing it. When tongue mobility improves, a switch to some other (edible) object is useful.

- Posterior tongue movement – practices transporting a bolus through the oral cavity to the back of the mouth, ready for the swallowing position. One way to practice this is to place a soaked piece of gauze on the tongue (with one end sticking out of the mouth so that one can hold it while practising) and trying to move it to the back by elevating the tongue and squeezing the liquid from the gauze.

- ‘Tongue cupping’ – practices holding a bolus in the mouth, by placing a practice ‘object’ on the tongue, then holding it strongly with the help of the tongue against the roof of the mouth / hard palate, with the tip of the tongue kept behind the front teeth and the sides of the tongue in contact with the buccal side of the upper teeth (or gums, if somebody has no teeth), then alternating this effort with a relaxed period several times.

- A range of exercises to improve general tongue mobility and strength (see below) are also helpful to improve bolus manipulation.

It is a good idea, representing little rewards along the way, to celebrate progress made after days and weeks of practising with an appropriate, newly manageable, food treat – it is astonishing how much of a motivational kick this can provide and how much of a return to normality such small steps can represent.

Exercises to improve tongue mobility and strength

This group of exercises is designed to improve the range of motion of the oral tongue and/or the base of the tongue. The general approach is to increasingly stretch a structure to its maximum non-painful extent, hold the position for a few seconds, relax, then repeat the cycle several times. There are suitable exercises for all structures that are relevant for swallowing. It may be useful as a motivational prompt to note that studies have convincingly shown that these kinds of exercises, started early after surgery (within three months of treatment) and carried on for several months lead to significantly improved recovery of swallowing function in the longer term.

- Oral tongue mobility exercises – practice the general range of motion of the tongue, by increasingly stretching the range of motion in all directions (sticking tongue out, stretching tongue sideways into the left & right corners of the mouth, raising the tongue and/or raising the tongue while lowering the mandible, retracting the tongue, yawning (some further exercises to improve jaw movement ranges are demonstrated in videos on our pages about physiotherapy). This needs constant repeating and practising to achieve noticeable improvements.

- Tongue base mobility exercises – practice the retraction of the tongue, which in turn is essential for the transport of a bolus toward the pharynx – by repeatedly retracting the tongue as far back as possible, by repeated exaggerated yawning, and by mock gargling. Most of the swallowing manoeuvres (see above), including various supraglottic swallowing methods, effortful swallow and the Mendelsohn manoeuvre double up as exercises to improve the tongue base mobility and the tongue retraction range.

- Tongue strengthening exercises – practice resilience / strength of the tongue muscle so that the swallowing process can be better supported by the tongue, by holding various tongue positions against some resistance (such as the back of a spoon, or a spatula) for a period of time, repeatedly, and over time increasing the resistance. Resistance to exercise the tongue strength can also be found in the oral cavity (for example, holding the tongue against the inside of the cheek whilst exerting pressure with the fingers on the outside of the cheek). Most of the tongue mobility exercises (see above) also strengthen the tongue, or can be practised against some form of resistance for better effect.

Exercises to improve airway protection

Airway protection is essential when aspiration is a problem, in order to restore safe oral food intake. Exercises that facilitate and improve voluntary airway protection can make all the difference between being able to feed oneself orally, or having to rely on enteral feeding.

- Some swallowing manoeuvres (super-supraglottic swallow, Mendelsohn manoeuvre) also function as swallowing exercises, they tend to improve the timing of the swallowing process by a prolonged elevation of the larynx, or by manipulating / closing of the vocal folds.

- ‘High-pitched voice’ – involves making noises at the highest possible pitch (falsetto voice) that can be maintained for a period of time. This activity considerably elevates the larynx. Sustained and improved ability to elevate the larynx (during swallowing) is a very good mechanism to protect the airway.

- Head lift (Shaker exercise) – involves lifting the head from a supine position, either to hold the elevated head position or to repeat the lift several times (or both). These are general strengthening exercises for a number of neck muscles (the suprahyoid muscle complex) important in the pharyngeal phase of swallowing, aiming to enable better larynx elevation and functioning of the upper oesophageal sphincter.

Brief overview of typical maxillofacial dysphagia circumstances

A very brief overview of some dysphagia aspects in oral & maxillofacial surgery highlights the wide range of difficulties encountered in just this field, across all ages, degrees of severity, short- and long-term, and as a symptom of many different underlying conditions. Swallowing difficulties roughly correlate with the structures affected.

- Cleft lip

and palate:

- common problems include lengthy feeding times, poor food intake, nasal regurgitation, choking & gagging, excessive air intake, stress (for all involved);

- common management approaches include a temporarily restricted diet (after surgery), bottles with special nipples or spoon feeding (and placing the nipple on the hard palate for stable compression), bottles with slow-flow nipples to reduce nasal regurgitation, obturators, semi-upright positioning (breast feeding only works for lip-only and palate-only clefts, it is not an option for cleft lip & palate), temporary enteral feeding, monitoring of nutrition and hydration.

- Craniofacial

anomalies:

- common problems include impaired sucking, airway obstruction, insufficient lip seal, drooling, limited range of motion in jaws, lips or tongue (microsomia usually unilateral);

- common management approaches include enteral feeding, special positioning for feeding (to optimise tongue movement), special soft bottles that can be squeezed to assist sucking, special nipples, feeding exploiting the stronger side of mouth.

- Head trauma:

- common problems include poor lip seal, trismus, slow movements, abnormal chewing, abnormal oral reflexes, impaired tongue motility;

- common management approaches include a range of exercises to support general recovery and restorative dentistry, where appropriate; there may be need for temporary enteral feeding.

- Head and neck

malignancies:

- generally speaking, the nature of dysphagia problems encountered depends on size, type and location of the tumour(s) as well as on the chosen treatment modalities, with a crude subdivision of ‘typical’ symptoms following surgery (with/without reconstruction), and those following radiotherapy;

- common problems after surgery include poor bolus manipulation (for example, from scaring of the tongue or from reconstruction that tethers the front of the tongue and thus impairs tongue base retraction), with prolonged oral phase, food and/or saliva residues, impaired airway protection, poor swallowing efficiency, sensory deficits (for example, leading to reduced swallowing reflex), reduced mouth opening, abnormal chewing;

- common problems during & after radiotherapy include acute mucositis during a course of radiotherapy; and often severe long-term effects on swallowing, including xerostomia (dry mouth), trismus (mainly caused by soft-tissue fibrosis), impaired tongue mobility (also a consequence of fibrosis), soft and/or hard tissue necrosis, slow bolus processing, residual food and/or saliva, impaired airway protection, strictures, persistent dysphagia for years and/or worsening over time (as a consequence of increasing fibrosis after radiotherapy, despite intensity-modulated irradiation schemes).

- it is quite impossible to sketch a ‘common management approaches’ list other than stating that all of the above mentioned assessments and management approaches play a role for this patient group; with need for repeated and prolonged support, often over many years.