Practical guide to oral hygiene

Contents

Below we discuss several aspects of oral hygiene, many of which touch on the theme of how best to help oneself and to best look after oneself. Some practical aspects, such as tooth brushing technique, are also demonstrated in video clips.

Plaque

Dental plaque is just one example of a natural biofilm. A biofilm can be described as a community of micro-organisms attached to a surface. These cells cannot be removed by simple rinsing (they are irreversibly associated) and are spatially organised into a three-dimensional structure enclosed in a matrix of extracellular material. Biofilms may form on a wide variety of surfaces, including indwelling medical devices, water system piping, natural aquatic systems and living tissues in general. Each biofilm is unique, with some universal structural attributes.

The dental plaque biofilm is unique to the oral cavity and enamel surfaces of teeth. It is comprised of over 700 known different bacterial species and more are yet to be characterised. Within this biofilm the bacteria are able to interact, communicate and gain benefits from each other. This degree of organisation makes a biofilm resilient and difficult to manage. It also increases its virulence. Bacteria from the aerobic streptococci genus are commonly found. Anaerobic bacteria such as fusiform and spirochete species are found in deeper layers of plaque and can have more pathogenic affects. Fungi, such as candida albicans and viruses, such as herpes simplex are also found in plaque.

The matrix in which these microorganisms are held provides an abundant food source for the bacteria. The matrix is formed from proteins and carbohydrates (from food debris), dead cells, blood cells, lactic acid, mineral salts and enzymes, and toxins produced by the bacteria.

Plaque biofilm is present on virtually all tooth surfaces. It begins to reform gradually approximately 60 minutes after cleaning. Following an initial binding of bacteria to the surface of a tooth, the thickness of plaque will increase as more bacteria bind and grow. This is a natural process and is actually part of the body’s host defences. However, plaque can accumulate to levels that are not compatible with health, predisposing sites to oral diseases, mainly dental decay and periodontal disease (gum disease).

Periodontal disease, in particular, is also known to have effects on systemic health, due to the infectious (bacterial) and inflammatory nature of the disease. Links between periodontal disease and diabetes, cardiovascular disease, adverse pregnancy outcomes and respiratory disease have long been established. More recently, an association between periodontal disease and Alzheimer’s disease has been suggested, and research into other conditions continues. There are a number of different mechanisms by which oral and systemic diseases are thought to be linked.

Bacteria at the tooth / gingiva interface are able to enter the periodontal tissues and may elicit a transient bacteraemia (presence of bacteria in blood). This is more likely to occur for severe and ulcerated periodontitis. In such cases, simple day to day tasks like chewing and brushing teeth, or having dental treatment can cause bacteraemia. Usually the bacteria are eliminated quickly, however if they are able to find favourable conditions they may multiply (actinomycosis is an example where commensal (friendly) bacteria of the oral flora invade deeper tissues and cause chronic infection). Having bacteria ‘where they shouldn’t be’ is generally detrimental to health.

Another mechanism by which systemic health is thought to be affected is by inflammatory injury by the body’s innate immune system. When bacteria initiate a local response at the gingival crevice (narrow gap between the crown of a tooth and the gum), this initiates a wider systemic response. Bacteria can also release toxins which, once in the circulatory system, can induce vascular pathology.

The adaptive immune system can also be affected. Persistence of inflammation both at the gingiva and deeper in the periodontal tissues leads to B cell and T cell activation (these types of white blood cells are part of the body’s targeted defence response to specific infectious agents). These processes contribute to further periodontal tissue destruction and eventually can lead to systemic inflammatory conditions such as some forms of cardiovascular disease.

It is said that if one stretched out all the subgingival tissues in the mouth, it would cover the area of the palm of the hand. Having ulcerated, chronically inflamed tissue of such an extent on the leg or arm would surely not be ignored. It is important not to ignore periodontal problems, just because they cannot be seen or may not cause serious symptoms early on.

Regular cleaning of teeth for plaque removal limits the chance of these plaque-related diseases occurring. Mechanical removal, brushing, is the only true way of removing this build-up of plaque by disrupting the maturation of the bacterial community from forming the plaque deposits.

Within minutes of brushing, the salivary pellicle, a thin protective layer of saliva covering dental surfaces, is created by the various salivary proteins. This protective layer acts as a receptor for early bacterial colonisation. At this stage, the connections are weak and can very easily be interrupted.

If left alone, the initial colonising bacteria begin to produce substances which anchor them more firmly to the pellicle. This increases the adhesive properties of plaque, making it harder to remove.

As the process continues, the bacterial colonies begin to produce CO2 and to excrete waste products. This makes the environment more attractive to anaerobic and Gram-negative species of bacteria. At this point the plaque is even thicker and denser, making it increasingly more difficult to remove. As further thickening occurs some bacteria may die or even break off, forming new colonies at other sites. Bacteria continue to reproduce and the cycle continues.

This is the reason why so much focus is placed on tooth brushing and interdental cleaning (see below).

Tooth brushing targets the removal of plaque from the gingival (gum) margin, pits and fissures of the teeth as well as the smooth surfaces. Interdental cleaning targets the proximal areas, the tooth surfaces between teeth (Figure 1). The gingival margin, pits, fissures and proximal areas, are all stagnation areas for plaque, and are common areas for dental decay and periodontal disease to develop.

In its initial stages, plaque cannot be seen by the naked eye due to its microscopic nature. As plaque thickens, it may be seen as sticky, white to yellow deposits. It can be felt by the tongue and is often described as a ‘fuzzy’ or ‘furry’ texture. Use of a ‘disclosing’ solution or tablet can make identification of plaque easier and can be used at home to aid better cleaning. The substances (food dyes) stain plaque, allowing easier identification of plaque before and after brushing (Figure 2). Children tend to be fascinated, and motivated, by the colourful ‘before’ and ‘after’ effect.

Tools

There is a bewildering choice of tools available for all kinds of oral hygiene purposes. Fortunately, this also includes some specialised tools for times when brushing teeth may be difficult.

Brushes

Brushing of teeth and gums can be undertaken with a manual toothbrush or electric toothbrush. In some instances, it may not be possible to brush due to pain or restricted access (for example, trismus (difficulty opening the mouth) can make tooth brushing difficult or impossible).

Electric toothbrushes may be more effective at removing plaque than a manual toothbrush; there is an ongoing debate about this. There are different types of electric toothbrushes available and the technique for each is slightly different.

Ideally an electric toothbrush should be rechargeable. The two main types are oscillating/rotary and sonic. Neither type is superior, therefore the user should pick a brush which suits best, with which they feel confident and comfortable with, including consideration of cost and ‘features’.

With an oscillating/rotary brush the head of the brush moves. These heads are mostly round in shape and so can fit around the shape of the tooth well to remove plaque. In sonic brushes, the head does not move but vibrates at a very high rate. With both types no scrubbing / brushing motion is required from the user.

Manual toothbrushes come in all manner of shapes, sizes and hardness of bristles (Figure 3). Many commonly available brushes have large heads but the most widely recommended and easy to use would be a brush with a compact / small head. This allows the brush to get around teeth more precisely and easily. A medium firmness is generally recommended, but for many people a soft or very soft brush is the preferable choice.

Manual toothbrushes can come with wider, chunkier handles if dexterity is an issue. A regular toothbrush can also be altered for better grip. For example a sponge ball can be placed around the brush handle. Or a dental professional could use putty to mould to the individual’s hand for a personalised grip (Figure 4). Electric toothbrushes often have a larger chunkier handle and as no brushing motion is required from the user, might be the best option for those who struggle with manual tooth brushing.

All tooth brushing should employ a systematic approach. This allows all tooth surfaces to be attended to. The buccal surfaces (facing out), the palatal & lingual surfaces (facing into the palate and tongue) and occlusal surfaces (the biting surfaces) must all be brushed. Brushing should take at least two minutes. Many electric brushes have timers to help manage this. Manual brushes and the heads of electric brushes should be replaced regularly, approximately every three months. A good test is to turn the brush head away and if the bristles can be seen splaying out then it is definitely time to change the brush as it is no longer effective (Figure 5).

Below we recap briefly the basic brushing techniques for manual and electric toothbrushes. The techniques are also demonstrated in videos.

- Rotary technique – When brushing the buccal & palatal / lingual surfaces, the brush should be angled so that the gingival margins are included. Each tooth should be brushed individually, a cupping motion around the tooth is advised. Brushing is completed by running the brush gently over the occlusal (biting) surfaces. No brushing motion is required from the user.

- Sonic technique – This is similar to a normal manual brushing technique. The brush is placed at a 45 ⁰ angle towards the gum margin when brushing the buccal and lingual / palatal surfaces. A slow approach moving along the margin, again, with no brushing motion is followed. Brushing is completed by running the brush gently over the occlusal surfaces.

- Manual technique – The brush is angled again at a 45 ⁰ angle towards the gum margin for the buccal and lingual / palatal surfaces. A gentle circular motion or short horizontal, gentle scrubbing, motion is used to remove plaque. Then the occlusal surfaces are also brushed. It is important not to apply too much force as this can wear gums away or cut into teeth over time. Brushing ‘from the wrist’ rather than ‘from the elbow’ allows for a more gentle approach.

Interdental cleaning aids

As with toothbrushes, there are many types of interdental cleaning aids. A common misconception is that these aids are used to remove food debris (like a toothpick would). However, the purpose of interdental cleaning is to clear plaque from the spaces between teeth. Tooth brushing alone does not reach these spaces and without interdental cleaning approximately 40 % of the tooth surface will remain uncleaned.

It is important that every user finds something that works for them. If it is difficult and frustrating, it is less likely to be used. It is recommended to undertake interdental cleaning at least once per day before brushing so that any debris or plaque dislodged is swiftly removed by subsequent tooth brushing. Toothpaste does not need to be used, but a dental professional may recommend using a fluoride or antibacterial chlorhexidine gel if required.

When interdental cleaning is taken up, it is likely that the gums will bleed. This bleeding is not due to damage or trauma, if the cleaning has been carried out correctly, but due to inflammation in these areas. It is common to experience some bleeding at first, but with regular, well performed interdental cleaning each day bleeding should reduce and stop over a couple of weeks.

Interdental brushes come in different sizes, size is normally indicated by a colour, and colours change depending on the brand. Handle styles are also different according to brand (Figure 6).

If gripping the brush is difficult, a long-handled or wider-handled interdental brush may be best. If one is struggling to reach difficult areas at the back of the mouth, a long-handled brush may be more effective.

The brush used should fill the interdental space for the best level of plaque removal, it should not snag or stick. A smooth motion when placing in and removing is ideal. Different areas may require different sizes of interdental brushes.

The gums are not flat, on the upper jaw they slope down gently and slope up for the lower jaw. The interdental brush should be placed in the space following this incline. Once in place, the brush should be gently moved so that it cleans each tooth, and then gently removed. Bending the brush can help it to be sturdier, especially for posterior teeth. Being gentle is also key, as a rushed forceful approach may add to the risk of the brush curling and bending. The technique for interdental cleaning is also demonstrated in videos.

Rubber tips also come in different varieties, they are used in the same way as interdental brushes (Figure 7). Some people find rubber tips easier to use as they do not bend as much and may be easier to access tight spaces. Although not as effective as brushes, rubber tips might offer a ‘good enough’ alternative.

Floss may be for some areas the only interdental-cleaning option, or it may be the generally preferred option (Figure 8). It must be used safely and correctly to be effective. Traditional floss can be quite bulky, so a floss tape is better advised. Floss can be used wrapped around the fingers or ‘flossettes’ are available which provide a handle for easier management. This handle can be short or longer, like a toothbrush handle.

Floss should be introduced from the top of the tooth, through and down into the interdental space. This should be a gentle motion. Once in this space, the floss is brought against each tooth. It is often described as making a ‘c-shape’ or ‘hugging into’ the tooth. It is then gently removed. No ‘see-sawing’ motion is necessary, a simple gentle removal of plaque is all that is required.

Superfloss (Figure 9) is a special type of floss which can be used around bridge work. It has a thinner ‘threading end’ and a thicker floss attached to it.

The thinner end is threaded in an area to allow access for the floss to pass underneath the bridge work to remove debris and plaque. It should not be used for regular interdental spaces.

Air & water flossing is becoming increasingly common. A flossing unit is used with a tip that is placed into the interdental space and water and/or air is used at high pressure to mechanically remove plaque / debris. Some people may find it easier (and easier to control) to use a plastic syringe for exactly the same purpose, especially when mouth opening is limited.

Toothpastes and mouthwashes

Toothpastes

A toothpaste containing fluoride is recommended for everyone. Fluoride has a role in the prevention of dental decay. There are several ways in which it is believed that fluoride ions take on this protective role. Fluoride ions promote the remineralisation of tooth enamel in areas where the tooth may have already begun a process of demineralisation. Fluoride ions also work to convert hydroxyapatite (the calcium mineral found in enamel) into fluoroapatite which is less soluble in acids created in the development of caries.

A pea sized amount of toothpaste should be used when brushing. It is important to spit out after brushing but not to rinse the mouth. Rinsing means the fluoride is washed away not allowing for any benefit to the tooth tissues. The highest amount of fluoride possible should be used. In shops, the highest amount of fluoride ions in toothpaste available is 1450 parts per million (ppm). Information about the fluoride content can be found in the list of ingredients on a toothpaste tube.

Sometimes a toothpaste with an even higher amount of fluoride is appropriate. This is the case when there is an increased risk of dental decay, for example for people afflicted by xerostomia (dry mouth) or trismus (difficulty opening the mouth). High fluoride-content toothpaste may also be used as a precaution in the daily oral hygiene management following radiotherapy of the head and neck region. These types of toothpastes need to be prescribed by a dentist or doctor.

Sometimes toothpastes can be uncomfortable to use if the oral tissues are particularly dry or sensitive following treatment. Strong mint flavours can give a burning sensation to the mouth. This is unpleasant and may deter someone from continuing with a regular tooth-brushing regime. Using a flavourless or mildly flavoured toothpaste can help with this. It may also be preferable to use a toothpaste free of sodium lauryl sulfate. Sodium lauryl sulfate is added to many products, not just toothpastes. It is a detergent and foaming agent and can act as an irritant (or even allergen), and can exacerbate dry-mouth problems. Toothpastes free of sodium lauryl sulfate are available, checking the list of ingredients on the toothpaste package will provide this information.

Some people choose to use a variety of whitening toothpastes (including the latest hype in black toothpastes, containing carbon black as the active ingredient). However, there is no evidence that they actually whiten teeth. These toothpastes tend to be very abrasive which is not good for teeth and should be avoided.

Mouthwashes

Using a mouthwash should never be thought of as a replacement for good daily tooth brushing, but it may have its place for some individuals at specific times and circumstances. If a mouthwash is being used in addition to brushing, it should be used at a different time to brushing as not to wash away fluoride from toothpaste.

Chlorohexidine mouthwashes are often advised following oral surgery to help inhibit plaque growth and for its antimicrobial properties. It is not recommended for long term use but may be used as an adjunct to brushing when the risk of infection is high or when brushing is simply not possible.

Chlorohexidine can cause staining of the teeth and ideally should not be used for more than two weeks at a time, where possible. An alcohol-free preparation should be used as alcohol-containing preparations can dry the oral tissues. Chlorhexidine mouthwashes can be quite harsh on oral tissues, so are not recommended for patients with oral mucositis as a common adverse effects of chemo- and/or radiotherapy in the treatment of head and neck malignancies or other malignancies such as lymphoma or leukaemia, or when suffering from other oral mucosal lesions.

Instead, saline rinse can be used if oral tissues feel sensitive. Some studies have shown that this can improve physical and social-emotional quality of life measures for people experiencing painful oral mucositis. Saline solutions can be made at home from salt mixed with boiling water and left to cool. Professionals may also provide ready-made saline solutions as mouth rinses. Also saline mouth rinses should be used at a different time to brushing teeth, to allow for full protective effect of fluoride in toothpaste (if using toothpaste at the time).

A fluoride-containing mouthwash used at a different time from brushing can add a fluoride boost throughout the day. Having this extra exposure of fluoride to the teeth can be helpful in a preventative approach to dental caries. Often these mouthwashes can be quite strong in flavour so should be used with caution. It is also advisable to check that the mouthwash chosen is an alcohol-free preparation.

Oral hygiene in difficult circumstances

Motivation to achieve good oral hygiene can be a struggle for anyone at times. During and after treatment for oral cancer, be it surgical and / or radiotherapy modalities, the motivation to do anything may slip. It is, however, enormously helpful in many regards to be kind with oneself and help oneself by trying to maintain good oral hygiene standards – it is a major contribution toward optimal outcomes. Tools and ‘tricks of the trade’ exist to deal with difficult and unconventional situations, some of which we describe below.

Pain

Pain when undertaking oral hygiene practices is common, especially after oral surgery, when mucositis occurs during chemo- and/or radiotherapy, when there is infection, or after trauma. It is important to employ common sense in these situations. Removal of plaque is important and can reduce the chance of further problems developing. However, conventional oral-hygiene approaches at such times may not be appropriate and in fact may be harmful both physically and also psychologically. A bad experience can deter one from trying again (similar arguments about avoiding disappointment and frustration apply to eating and avoiding former favourite foods until one is fully fit to enjoy them again).

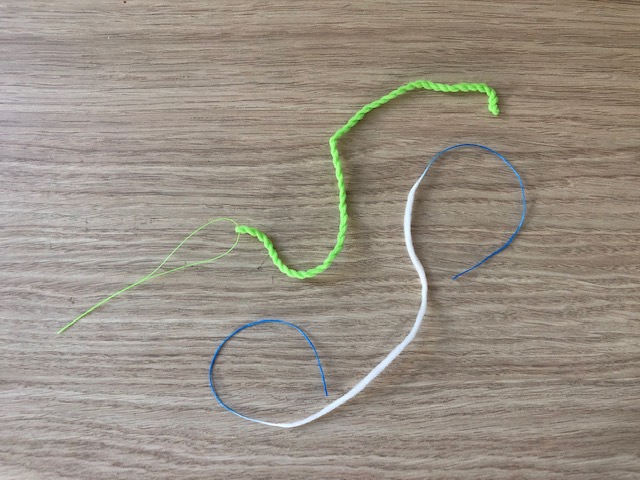

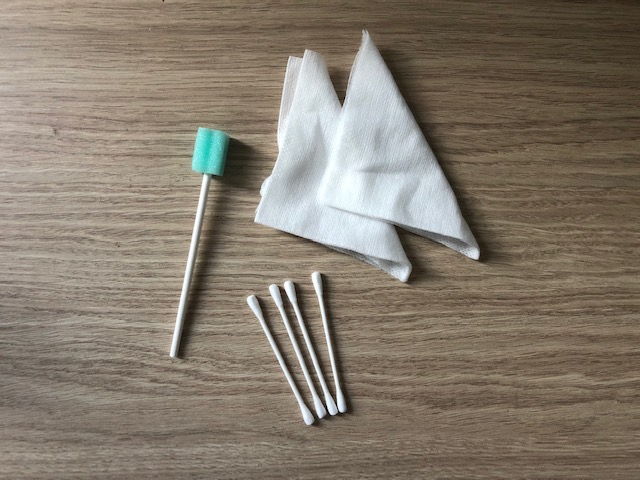

Using a soft or super-soft toothbrush is advised. Failing this, moist gauze or even cotton buds or swabs can be used to remove plaque that is accumulating (Figure 10). Sweeping them along the gum margin gently, where it is possible, is best. It may be that some areas of the mouth are more tolerable then others. It is fine if the whole mouth cannot be cleaned as at normal times. This is a realistic and pragmatic approach, and ‘normal’ practices can be resumed gradually and as soon as possible.

The intensity of mint flavours in toothpastes and mouthwashes (see above) can induce pain and discomfort. Using a sodium lauryl sulfate free (see above), non-flavoured toothpaste may also help. At times it may not be possible to use any toothpaste.

If mechanical removal of plaque by brushing is (temporarily) impossible, a mouthwash may be more tolerable. Although mouthwash will not remove the plaque, some mouthwashes at least inhibit the growths of bacterial colonies (bacteriostatic effect). Alcohol-free chlorhexidine mouthwash, including non-staining preparations, has such properties.

Some days it may not be possible to remove plaque with any of the methods. This is normal and no reason to despair. Establishing a good oral hygiene regime as soon as possible, but only when ready is completely acceptable and follows the wisdom of common sense.

Difficult access / trismus

Trismus can present many difficulties and frustrations, and make ‘normal’ oral hygiene practices feel incredibly difficult. It is important to think ‘outside the box’ at these times. It is unlikely that thorough brushing in all areas of the mouth will be possible, but trying to complete as much as possible cannot be stressed enough.

Completing some sort of oral hygiene regime is still of the utmost importance as prevention is key. People suffering from trismus may be at a higher risk of dental decay due to a liquid diet. Trismus also makes restorative dental or periodontal treatment difficult, so preventing problems from occurring is particularly important.

As always, brushing teeth in front of a mirror is recommended so that one can see what us actually being done in the mouth. Soft tissues, such as lips and cheeks, may need to be actively (but gently) moved out the way to allow better access. This can be difficult when skin is tight, but perseverance is key. Asking a dental professional for a plastic dental mirror may be an option. It can be used to retract cheeks and lips to allow for better access. Using a finger to touch where aiming to brush, then placing the toothbrush on top of the finger can also help. This is particularly useful if sensation has been lost in some areas of the mouth.

A toothbrush with a small compact head (manual or electric), or even a child’s brush is recommended. Single tufted brushes may also have their place for better access for those hard to reach areas. For interdental cleaning long handled interdental brushes (see above) are available, or consideration of a water or air flosser might be a good alternative. Water or air flossers (or some plastic syringes) often have long narrow attachments to direct the water/air flow and thus take less space to fit into the mouth than a finger holding an interdental brush.

Nil by mouth status

It is a common misconception that teeth are solely brushed to remove food debris, this is not the case. Even when on a ‘nil by mouth’ diet, plaque still needs to be removed.

It is important to determine whether somebody has a ‘safe swallow’ when thinking about tooth brushing. This will often be discussed with the treating clinician or the speech and language team. If somebody is not able to swallow safely and there is a risk of aspiration, brushing teeth gently without toothpaste may be a good practical solution. There are also suction toothbrushes available which can be an aid to reduce the risk of aspiration. Using a non-foaming toothpaste may also have its place, as this can be less distressing.

Fungal infection

Oral fungal infections are common following treatment for head and neck cancers. Xerostomia can make the mouth a breeding ground for such infections, as can struggling to maintain good oral hygiene, as well as having lower immunity.

It is important to recognise the signs and symptoms of oral fungal infections. Candida albicans which gives rise to oral candidiasis or ‘oral thrush’ is the most commonly seen. Unfortunately, with thrush really good brushing is important even though the mouth can feel very sore and uncomfortable. Using a very soft, small toothbrush and soft interdental brushes can help to remove plaque. Candida may be living in the plaque film. The tongue is also an important area to clean as plaque can accumulate there as well, especially if xerostomia is an issue.

Using a tongue scraper can help. These devices are specifically designed for cleaning the tongue (Figure 11). A tongue scraper is placed at the back of the tongue and pulled gently forwards then washed under a running tap. This should be repeated until the tongue looks clean.

A toothbrush can also be used to brush the tongue. This should be a different toothbrush to the one used for brushing the teeth and gums. As with the tongue scraper, it should be thoroughly cleaned. Cleaning the tongue has the additional benefit of maximising the sense of taste, which may be compromised by the presence of thick plaque on the back of the tongue.

Dentures can be a source of fungal infection, so daily cleaning practices should be undertaken thoroughly (see below). If simple oral-hygiene practices are not helping the situation, it is advisable to seek advice from a dental professional as an antifungal medication may be required to treat the problem systemically as well as locally through excellent oral-hygiene practices.

Lone standing teeth

Where teeth are lost, there will be gaps in the dentition. In some cases, this ends up with a lone standing tooth, a tooth that does not have any other teeth adjacent to it. Plaque adherence around a lone standing tooth can become a problem.

Such teeth can be missed in the brushing routine, especially if they are quite far back in the mouth. There is also more surface for plaque to adhere too. The mesial (front) and distal (back) areas of these teeth may also be missed as a regular toothbrush does not fit well in these areas. As mechanical plaque removal by thorough brushing (see above) is the only true way to stop plaque build-up, lone standing teeth may require a dedicated brushing routine. Large interdental brushes can be very helpful for brushing these teeth when used on the mesial and distal surfaces, using the regular toothbrush for the gingival margins (Figure 12). A single tufted brush can also be of use here as it is compact enough to be used all around the tooth.

Lone standing teeth, like all teeth, are important. However, in some instances they become even more important as they might be the only tooth left in certain areas of the mouth. Maintaining these last remaining natural teeth helps maintain bone levels in the jaws. Without teeth, the jaw bones resorb and shrink. However, having a good level of jaw bone is important when prosthesis is being designed, be it dental implants, dentures or bridges. Beyond helping to maintain healthy jaw-bone levels, lone standing teeth may have an additional role in securing or supporting required prostheses.

Supported oral hygiene

For some people it may be difficult or impossible to undertake daily oral hygiene practices due to mobility or dexterity issues. Following some surgical interventions, there may need for a period of recovery until arms and hands are healed. Other medical issues may lead to a reduction in fine motor movements required to perform oral hygiene effectively.

As oral hygiene is so important, asking for help is a good option. For some this may mean putting pride aside. There is no harm or anything to be lost in asking for some support. This might mean someone else is completing all of the brushing, or maybe just helping with difficult to reach areas.

When assisting with tooth brushing it is important that the head of the person having their teeth brushed is well supported. Having the person sitting rather than standing can help with this. The person assisting should ideally be standing behind the person slightly to one side. This allows for good vision and provision of head support. The person assisting may need to gently move the soft tissues, such as the lips and cheeks with a finger to help with access to teeth and gums. Brushing is in the systematic way so as no areas are missed. Using a non-foaming toothpaste can help the person assisting to see better in the mouth.

Care of prostheses

Dentures

There are different types of dentures falling into two categories, full / complete and partial dentures. Different materials can be used to create dentures, acrylic or chrome, or some combination of both. Regardless of the type and material, dentures need to be cared for to ensure good oral health.

Plaque and food debris can easily accumulate on dentures. This harbouring of microorganisms is harmful to the soft tissues of the mouth and leads to a higher risk of infections such as fungal infections by candida species. Poor care of partial dentures can increase the risk of decay and periodontal problems of existing teeth.

Dentures should be removed every night, cleaned and stored safely until being put back in the following morning. Dentures should be cleaned ideally after every meal. Where this is not possible at least once daily cleaning should occur.

Dentures should be cleaned over a bowl or sink filled with water this ensures should they be dropped they will not break. The technique is also demonstrated in videos.

All areas of the denture should be brushed with a ‘denture brush’ or soft toothbrush. This should not be the same brush used for natural teeth. A denture cleaning paste or fragrance-free liquid soap can be applied to the brush. Regular toothpastes may be abrasive, so it is not recommended to use them for regular cleaning of dentures. After cleaning, the denture should be rinsed well with cold water.

When not in the mouth, dentures should be stored in a solid container to protect them. It is not recommended that dentures are stored in a ‘denture cleaner’ solution as these can bleach / wash out acrylic dentures and corrode chrome. Any use of denture cleaner should follow the manufacturer’s instructions carefully.

Obturators

An obturator is a form of prosthesis to seal an opening in the maxilla between the oral and the nasal cavity after large surgical resections in the maxillar region. In some circumstances, an obturator can be a preferable form of oral rehabilitation over surgical reconstruction with free flaps.

There will be different obturators at different points in the treatment and recovery. An initial surgical obturator will be placed during surgery in the operating theatre right after the resection. This initial obturator will stay in place for a couple of weeks and it is not to be removed.

Another temporary obturator will then be placed. This second-stage obturator should be cleaned much like a denture – over a sink to avoid breaking should it be dropped, with a toothbrush or denture brush and a denture paste or fragrance free toothpaste. All surfaces of the obturator should be brushed to ensure bacterial plaque and secretions are removed. This kind of care and cleaning regime is also required for the third-stage, definitive obturator. However, in addition to daily cleaning it is recommended that a definitive obturator is removed for a period of time, overnight if possible, and kept in a moist environment (for example in a plastic container with a tight-fitting lid and with a small amount of water). The specialist providing the obturator should be able to advise when the time is right to begin removing the obturator for these prolonged periods. If special soft linings are used, advice will be given on how to care for these.

Some people may need to clean the soft oral tissues when the obturator is not in place. People affected by xerostomia are at a higher risk of dried secretions becoming lodged in and around soft tissues. These secretions can normally be removed with a damp brush or sponge swab. It is important to check these products as for some sponge swabs the sponge can become separated from the swab stick.

Care and use of an obturator is person specific and specific advice about the most suitable approach is best to be obtained from the team providing treatment.

With regard to oral hygiene, dental implants need to be treated with the same level of care as natural teeth. Tooth brushing is still required as is interdental cleaning. Seeking out a good hygienist / dental therapist / dentist can be very helpful. They can give tailored, personalised advice on the best equipment and techniques to clean effectively.

It is important to note that while dental implants obviously cannot be affected by dental caries, they are at risk of periodontal problems. Periodontal problems affecting implants tend to progress quicker than in the natural dentition. Periodontal fibres do not readily form between the implant and bone.

Bleeding around implants is a sign of poor oral hygiene and if not corrected with improvement in oral-hygiene practices may lead to the loss of the implant. It is advisable to seek examination and advice from a dentist if concerned about bleeding around implants whilst cleaning. Regular and thorough examination of the implants must also take place to ensure any issues can be detected early.

It is tempting to think that implants being placed can solve dental problems previously experienced. This is simply not the case. Care of dental implants requires the same level of motivation, time and diligence as should be given to oral hygiene for natural teeth.