Surgical endodontics

The different stages of surgical endodontics

- assessment for endodontic surgery;

- local analgesia;

- incision and raising of a suitable flap for access;

- haemostasis (reducing bleeding);

- identification of the root apex (tip of the root);

- periapical curettage (clearing the area surrounding the tip of the root);

- root end resection (apicectomy; removal of the tip of the root);

- root end cavity preparation;

- root end (retrograde) filling;

- wound closure;

- aftercare;

- assessment of success of the procedure.

are outlined in more detail below. The following page discusses some aspects of surgical endodontics related to different locations of teeth, revision of surgery, more recent developments of potential alternatives, and some additional general considerations.

Assessment for endodontic surgery

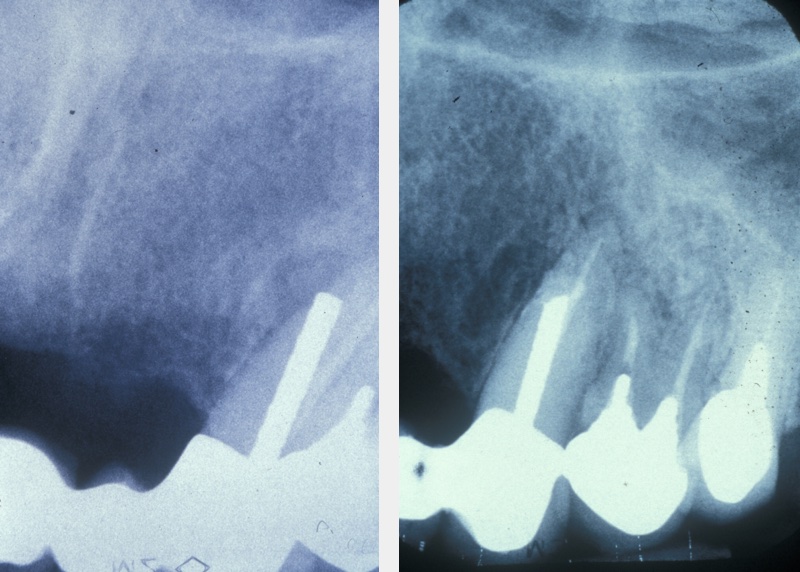

A medical history, clinical examination, and radiological examination should be performed when surgical endodontic treatment is being considered. Where applicable, previous conventional endodontic treatment (root canal treatment) is also assessed and a decision made on its effectiveness. Local anatomical factors, such as the proximity of the surgical area to the maxillary sinus (cavity above the upper jaw) or neurovascular bundles (important nerve and blood vessel structures) need to be taken into account, as does the feasibility of surgery. Figure 1 gives an example where periapical surgery was the preferable option over conventional treatment.

Local analgesia

Most surgical endodontic treatment can be performed under local anaesthesia . A careful technique at this stage ensures patient comfort throughout the procedure. Topical anaesthetic is applied to a dry mucosa (lining of the mouth), followed by a slow supraperiosteal injection (local infiltration) of 0.5 ml of the anaesthetic solution. Most of the discomfort resulting from the administration of local anaesthetic is caused by distension of the periosteum (dense layer of connective tissue covering bone). Therefore, the remainder of the anaesthetic injection is given slowly at a rate of approximately 1 ml/minute. In the maxilla (upper jaw), infiltrations are almost exclusively used, whereas in the mandible (lower jaw) nerve blocks should be supplemented with local infiltrations. Lidocaine as local anaesthetic with epinephrine (adrenaline) added in a 1 : 80 000 ratio is commonly used in the UK. During surgery, the vasoconstrictive properties of adrenaline help with haemostasis (minimising bleeding), with keeping the local anaesthetic confined to the local region during surgery, and with improving the quality and duration of the local analgesia.

Incision and flaps

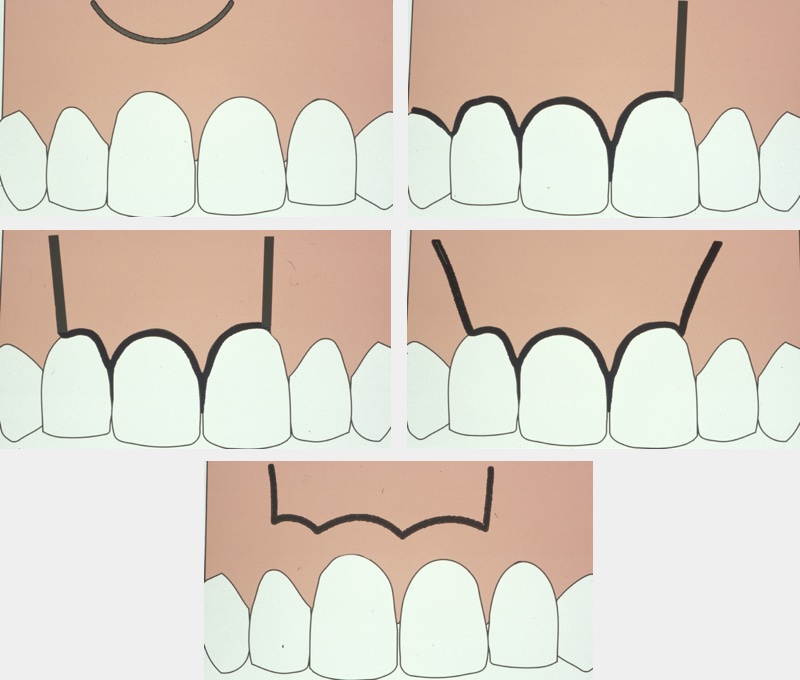

A wide variety of flap designs have been used, but the six main types are:

- semilunar;

- triangular;

- rectangular;

- trapezoid;

- vertical incision;

- Ochsenbein-Lübke flap (not common in Germany, where the distinction is made between marginal and para-marginal flaps).

Figure 2 illustrates the different types of flaps.

Whichever design is chosen there should be an unobstructed view of the operating area and good access for instrumentation. The triangular and rectangular flap designs are currently the most commonly used. Incision should allow a full thickness mucoperiosteal flap to be raised cleanly from the bone. Any relieving incisions should be made vertically rather than at an angle, and should avoid bulbous areas such as the canine prominence in the maxilla where root not covered by bone (and therefore having no useful surface blood supply) may prevent adequate healing of the flap margin. The flap is reflected from crown toward apex, starting in the sulcus, and it is kept moist and free of tension. This minimises any postoperative problems with gingival recession.

Haemostasis

Adequate haemostatic control is important during endodontic surgery to improve visualisation of the surgical area and thus to reduce surgical time and postoperative pain and swelling. It also allows the root-end filling (see below) to be placed under favourable conditions. The epinephrine in local anaesthetic solutions can significantly reduce intra-operative haemorrhage by acting as a vasoconstrictor [treatment-other-medication-miscellaneous-vasoconstrictor-vasodilator] in gingival (gum) blood vessels. Solutions with a 1 : 50 000 epinephrine concentration have been found to cause half the blood loss of those with 1 : 80 000 concentration, with no significant difference in systemic effects.

The design of the flap is also important when considering haemostatic control for endodontic surgery. The supraperiosteal blood vessels run parallel to the long axis of the tooth, and therefore vertical relieving incisions as opposed to angled ones will decrease the number of blood vessels severed. Furthermore, reflection of a full thickness periosteal flap which retains the microvasculature within the body of the flap also limits haemorrhage.

In addition to local anaesthetic solutions containing epinephrine and a careful surgical technique, a variety of haemostatic agents are available to effect adequate moisture control. These are usually used after periapical curettage (see below), commonly used haemostatic agents include:

- cotton/gauze with or without vasoconstrictor - these agents reduce haemorrhage by applying physical pressure and can be readily impregnated with a vasoconstrictor;

- oxycellulose - these agents provide a framework for clot formation (there have been reports of a foreign body reaction to the material together with delayed healing);

- wax - this exerts a pressure or tamponade effect to aid with haemostasis, but histologically a foreign body reaction is also shown to be elicited. It can sometimes be difficult to remove all of the wax from the bony crypt;

- calcium alginate - this agent aids haemostasis by stimulating coagulation via the release of calcium ions, Ca2+;

- calcium sulphate - this usually comes as a powder and a liquid which when mixed together form putty that can be placed into the cavity. This putty then exerts a tamponade effect and blocks the vascular channels;

- ferric sulphate - this is particularly useful for arresting multiple small bony bleeding points (however, it must be thoroughly rinsed out to prevent a foreign body reaction and abscess formation);

- gelatin - this acts by stimulating the intrinsic clotting pathway;

- collagen - this agent acts in a number of ways. In addition to having a mechanical tamponade effect, it also stimulates platelet adhesion and aggregation, activates Factor VIII and releases serotonin, which in turn causes vasoconstriction;

- tranexamic acid mouthwash given pre- and post-operatively is sometimes used to aid haemostasis by inhibiting fibrinolysis.

Identification of the root apex

If the lesion has perforated the cortical plate (hard, outer layer of bone), identification of the apex is relatively simple. However, if this has not occurred, an estimation of the tooth length from a good preoperative radiograph is made. A small round burr, running in a slow handpiece with water irrigation, can then be used at this length with gentle pressure to explore the area and locate the lesion. Care is required to avoid damage to the roots of the adjacent teeth. The bone is gently pared away until the root apex is located and further bone removed to provide good access.

Periapical curettage

Any soft tissue lesion is carefully curetted (removed) from around the apex with excavators and sent for histopathology examination if appropriate. Where possible, the lesion should be excavated in one piece and any remnants curetted out with sharp instruments. Sometimes, the tissue is firmly adherent to the apex, in which case the apex is resected and removed together with the soft tissue lesion.

Root end resection

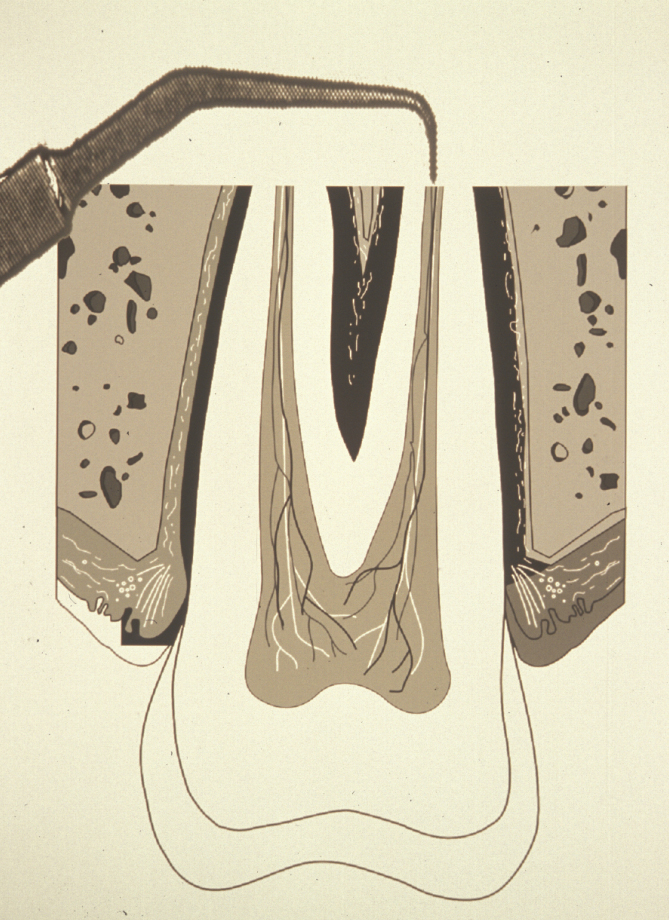

The aim of root end resection is to present the surface of the root so that the apical seal of the orthograde root filling can be examined, and to provide access for root end preparation. Approximately 2 to 3 mm of the root end is resected at right angles to the long axis of the tooth. A bevelled resection is avoided where possible because a larger surface area of dentinal tubules is exposed, which can lead to microleakage. Also, if the root end is bevelled, there is the possibility of leaving behind infected tooth tissue, or of missing part or all of the root canal system (Figure 3).

Root end resection is effectively an apicectomy, and although the term ‘apicectomy’ has been commonly used to describe apical surgery, it only describes a small section of the whole procedure and is, therefore best avoided.

Root end cavity preparation

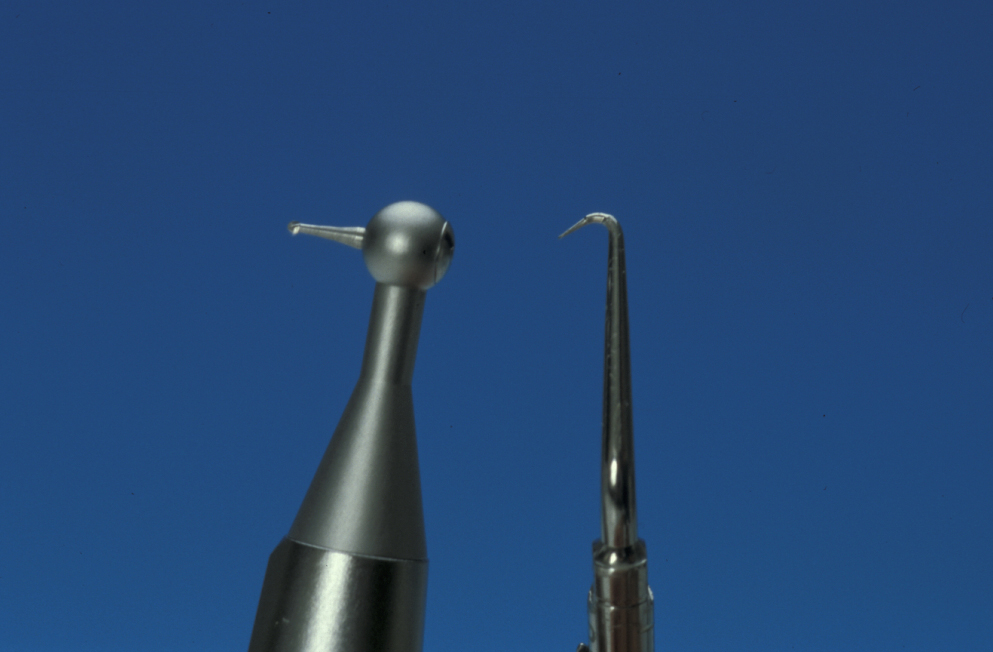

The ideal root end cavity preparation is defined as a class I preparation, at least 3 mm into root dentine with walls parallel to and coincident with the anatomic outline of the pulpal space. A contra-angled slow speed microhead handpiece with a small round burr has conventionally been used to prepare the cavity, but this does not relate to the anatomy of the pulp and often the apical dentine is weakened by unnecessary over- enlargement. There is also a considerable risk of perforating the root-end. Therefore, specifically designed ultrasonic instruments have been developed to create an accurate preparation. Their small tip size allows much greater access than even the microhead handpiece (Figure 4).

Ultrasonic instrumentation enables the isthmus (narrow connection) running between some canals to be prepared and sealed. This isthmus is often a reservoir for bacteria that have not been removed during conventional root canal therapy (Figure 5). In many developed countries the use of magnification and piezo (ultrasonic ) instruments are the accepted standard.

Root end (retrograde) filling

The purpose of the root end filling is to seal the apical section of the tooth and thus prevent any leakage between the oral environment and peri-radicular tissues. Before the root end filling is inserted, one of the haemostatic agents (described above) can be packed into the bony cavity to prevent contamination of the root end cavity.

In most situations a retrograde root filling is indicated. On occasions where the source of irritants is removed by the resection, and the rest of the canal is completely cleaned and obturated, it is acceptable simply to burnish the apical gutta percha. When a root end filling is to be used, there is a wide variety of materials available (Table 1), although not all are commonly used.

Table 1 Materials used for root end fillings

| Commonly used materials | Less commonly used materials |

|---|---|

| amalgam zinc oxide / eugenol mixture mineral trioxide aggregate glass ionomer composite zinc phosphate zinc polycarboxylate |

gutta percha gold foil teflon cyanoacrylate apatite cement gallium alloy |

Amalgam has been used for many years because it is cheap, easy to handle and not particularly moisture sensitive. However, there are problems with its dimensional stability and corrosion, and it can cause staining of the mucosa if carelessly placed. Furthermore, amalgam does not provide an ideal apical seal. It is no longer regarded as an acceptable root end filling material in many developed countries.

Zinc oxide / eugenol based materials have been used to good effect as retrograde filling materials. Leakage studies suggest less microleakage around these materials than amalgam, and because they are eugenol based there is some antibacterial activity.

Glass ionomer has been shown to give a better seal than amalgam by adhering to dentine, and it has antibacterial activity against some endodontic pathogens. As well as being placed in the root end cavity, a thin smear of glass ionomer can be used to seal the whole root end surface. Composite (organic polymer material) has also been used as a root end filling and, like glass ionomer, can be used to seal the root surface. Both glass ionomer and composite materials are very moisture sensitive, which is a distinct disadvantage in apical surgery.

Mineral trioxide aggregate consists of a fine powder of tricalcium silicate, tricalcium aluminate, tricalcium oxide and silicon dioxide. The mixture sets in the presence of moisture. Hydration of the powder produces a colloidal gel with a pH value of 12.5 (a strongly basic gel) that solidifies to a hard cement. Mineral trioxide aggregate has several reported advantages:

- very good sealing ability;

- low toxicity;

- very low inflammatory reaction to the material;

- an inductive effect on osteoblasts and cementoblasts (encouraging bone regeneration);

- no moisture sensitivity;

- low setting contraction.

The disadvantages of mineral trioxide aggregate are that it is relatively expensive and has a long setting time (4 hours) – although the initial set only takes several minutes. Despite this, current research is promising for the use of mineral trioxide aggregate in surgical endodontics, and it is the filling of choice for this purpose in most developed countries.

Wound closure

After placement of the root end filling material and débridement (cleaning) of the surgical area, the flap is reapproximated and compressed for 2 to 3 minutes prior to suturing. There is no evidence for the superiority of resorbable or non-resorbable sutures; 4-0 or 5-0 monofilament varieties have theoretical advantages. Cyanoacrylate adhesives and fibrin sealants have been used but are not widely adopted because of their unpredictable strength.

Aftercare

The postoperative use of anti-inflammatory analgesics may be advised. Chlorhexidine mouthwash, 10 ml rinsed twice daily is also prescribed. The use of prophylactic antibacterial agents is controversial. There is no current evidence base for this although many still use this technique or even use postoperative antibacterials, which has even less theoretical or evidence based support. Ice packs, which are also commonly advised by some, have no real evidence base.

Sutures may resorb or be removed according to personal protocol. An X-ray radiograph is taken at three months. Further radiographs are taken as appropriate to each individual situation.

Assessment of the procedure

Once endodontic surgery has been performed, it should be assessed after at least one year. Success is indicated by:

- absence of symptoms such as pain and swelling;

- no sinus tract (abnormal draining channel);

- no loss of function;

- satisfactory soft tissue healing;

- X-ray radiographic evidence of bony infill at the surgical site.

Figure 6 depicts the appearance one year after a surgical endodontics intervention. Long-term follow up is based on personal protocol after one year.