Hard tissue necrosis

Contents

Bone necrosis (osteonecrosis) in the head & neck region often occurs in combination with necrosis of adjacent soft tissues such as the skin or the lining of the mouth (mucosa). More information about this additional aspect of bone necrosis is on our pages about diagnosis and treatment of soft tissue necrosis .

Some general remarks

Having briefly outlined medical and surgical treatment options for the management of osteonecrosis of the jaws (ONJ) on the previous page, below we discuss these options in more detail. Any considerations about suitable, or less appropriate, treatment schemes for individual circumstances are closely linked to the different causes and hypotheses about the pathology of ONJ , be it necrosis caused by previous radiotherapy treatment (osteoradionecrosis, ORN), by medications that interfere with the bone remodelling process (medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws, MRONJ), such as bisphosphonates or denusomab, or other less common causes. However, in addition to such bone-pathophysiology focussed considerations there are many more aspects to take into account when choosing the individually most suitable treatment option(s) for ONJ.

Of the less common, but varied causes, of ONJ the most prominent ones are a range of infections. According to some recent microbiological studies, even latent and persistent periodontal disease, together with other trigger events, may be a significant enabling factor for the development of ONJ. Treatment of these underlying causes combined with local débridement is normally also curative for the resulting ONJ. Broadly, this is true for most, if not all, cases of ONJ that are not related to either radiotherapy or antiresorptive medications. In many of these cases the treatment of the underlying conditions, such as diabetes is not within the remit of maxillofacial surgery, so will not be discussed further here.

The situation is different for the two main causes of ONJ, radiotherapy or antiresorptive medications. There, the causes cannot be eliminated and treatment is aimed at managing the sometimes severe, consequences. Our discussion below addresses management needs of these two forms of ONJ.

ONJ caused by either of these two causes can occur in milder forms, more severe variations, and debilitating very severe forms. The underlying medical conditions that lead to radiotherapy treatment to the head and neck region (malignancies in the head and neck region), or long-term treatment with antiresorptive medications (most commonly to manage severe osteoporosis, but also in the management of bone metastases) in the first place are very different. This accounts for normally very different life situations and/or prognoses. Accordingly, similar extents of ONJ may call for different treatment modalities for the two causative factors and different life situations (see below).

As a general trend, milder forms of ONJ may be managed successfully with medical options and/or minor surgical interventions. More severe forms typically require more invasive surgical resection & reconstruction. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to the individually appropriate management of ONJ. Further, there are only a few firmly established facts and many myths, ambiguity, biased and poorly evidence-supported reports in the literature, about the pathophysiology of the condition as well as treatment modalities and protocols.

In very general terms, the greatest obstacle to effective treatment of all forms of osteonecrosis is the lack of understanding of the pathogenesis of these conditions. Accordingly, there are no clear ‘gold standard’ treatment recommendations, but there is ongoing debate about current treatment strategies.

Non-surgical treatment options

In most cases, clinical findings are that all forms of ONJ, including milder forms, are accompanied by some form of lesion and/or necrosis and/or infection of adjacent soft tissues, in particular the oral mucosa (parallels with osteonecrosis of the external auditory canal have been pointed out – a similar situation where bone is only separated by a thin layer from a heavily bacterially colonised area). With this fact in mind, classical and well-established management methods make good sense. Rigorous oral hygiene regimens, including ‘tricks’ for optimised self-care, and including chlorhexidine antibacterial mouthwash and/or irrigation of small exposed areas of bone and meticulous local wound care are essential. It has also been pointed out that more can be done to avoid the development of ONJ. Before starting therapy with antiresorptive or antiangiogenic drugs or radiotherapy, careful examination of the dental status (including prosthetics and/or implants) followed by all necessary dental treatments, and optimised oral hygiene as a starting point can be useful prevention strategies. This proactive strategy makes good sense in the light of recent experimental findings that existing periodontal disease may be a factor in the development of ONJ, possibly in a synergistic mode in combination with other infections or lesions developing later.

In addition, taking determined action as early as possible is the best chance to avoid (or delay) progression of ONJ from milder to more severe forms. In many cases, this will include a course of systemic antibacterial and/or antifungal agents to control local infections. Infections in areas afflicted by ONJ are typically caused by a range of bacteria that are commonly involved in dental infections, and are usually sensitive to treatment with standard antibacterial agents such as penicillin, amoxicillin, clindamycin or metronidazole. Sometimes it is useful or necessary to obtain more precise microbiological characterisation of the infectious species and change antibacterial and/or antifungal agents to more targeted choices. The duration of systemic antibacterial / antifungal treatment courses may vary considerably. Anti-inflammatory agents such as corticosteroids in combination with analgesia may be helpful during acute episodes.

This type of management leads to a resolution and healing of small ONJ lesions in most cases, time and perseverance permitted, and irrespective of the lesion being caused by radiotherapy or by antiresorptive medications.

An alternative medical treatment scheme for the management of ORN was suggested some time ago. The medication scheme is known as PENTOCLO, or triple therapy. The drug cocktail is based on the hypothesis that fibrosis (scar formation) and atrophy (tissue wasting) are the two main effects of long-term damage to soft tissue by high-energy radiation. Significantly, this hypothesis of explaining the pathophysiology of soft-tissue necrosis resulting from radiotherapy (in the treatment of breast cancers) does not actively consider infection(s) and does not take the particular conditions of the oral cavity into account, nor does it address differences in the pathophysiology of hard and soft tissues in their response to high-energy radiation damage.

Nevertheless, the suggested medication scheme derived from the fibrosis/atrophy hypothesis was adopted seamlessly for the medical treatment of ORN and later its use was even extended to include MRONJ. The scheme consists of three drugs:

- pentoxifylline , assumed to have anti-inflammatory properties;

- tocopherol , assumed to act as an antioxidant;

- clodronate , an antiresorptive agent from the group of bisphosphonates.

To date, there are no controlled studies of the efficacy of the scheme in the treatment of ORN, despite a number of publications claiming success. Most of these reports are on small groups of patients. Neither is there any substantive and convincing explanation of the exact working mechanisms of this drug cocktail, or even two of its components although there is plenty of speculation. On closer inspection, most of the publications originate from few groups, including the group who originally suggested the scheme for the management of soft tissue necrosis following radiotherapy in treatment for breast cancer. Most treatments reported as successful were achieved on small ORN lesions (which can also be successfully treated in more conventional ways; see above). PENTOCLO was used in several studies in conjunction with antibacterial agents and/or steroids, so any treatment success may just as well be attributed to these agents. In the reality of clinical practice, the PENTOCLO regimen is commonly five drugs, the regimen adding an antibacterial agent, ciprofloxacin and a steroid, usually prednisolone.

It seems at least counterintuitive to use a drug cocktail in which one component, clodronate, belongs to a group of antiresorptive medicinal drugs, bisphosphonates, known to be associated with medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (MRONJ). Schemes using a combination of pentoxifylline and tocopherol have also been used in the management of MRONJ, omitting clodronate from the cocktail.

The use of PENTOCLO medication schemes is controversial. In the light of the limited information available, in the UK the NICE (National Institute of Clinical Excellence) recommendation is to use these medication schemes only as part of a clinical trial, but not otherwise. There is a clear need for more rigorous investigations into this type of medical treatment scheme and its potential merits for the treatment of ORN and MRONJ.

This should include a step back to the basics, that is back to the laboratory to properly unravel the pathophysiology of ORN and MRONJ, alongside laboratory studies of the interaction mechanisms of the various medical agents with the physiology and pathophysiologies of bone. Of course, when we say ‘bone’ this is no more than an umbrella term for different types of bone, and of non-uniform properties of different types of bone in different parts of the skeleton, even just over the small area of the jaw bones, and necrosis associated with different causes.

Surgical interventions

In the same way as osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ), covers a wide range of severity from minor (and often non-symptomatic) lesions all the way to debilitating forms, there are variable degrees of invasiveness of surgical interventions to deal with ONJ.

There is mounting evidence that surgical intervention as the first-line treatment modality, whenever possible, has the best chances of success for resolving ONJ lesions at all degrees of severity. There are also indications that extensive surgery provides results superior to those of conservative surgical or non-surgical (see above) interventions. Increasing evidence suggests that the better success of sufficiently radical surgical interventions is likely to be related to the prolonged and often failing healing of these lesions under other treatment schemes. This failure, in turn, has been ascribed to the presence of necrotic and / or infected bone itself preventing recovery of the adjacent mucosa and subsequent healing of the affected site. Non-surgical treatment options can provide symptom relief, but closure of mucosal lesion(s) remains challenging in this way. If healing using conservative methods fails, then surgical intervention is the only option.

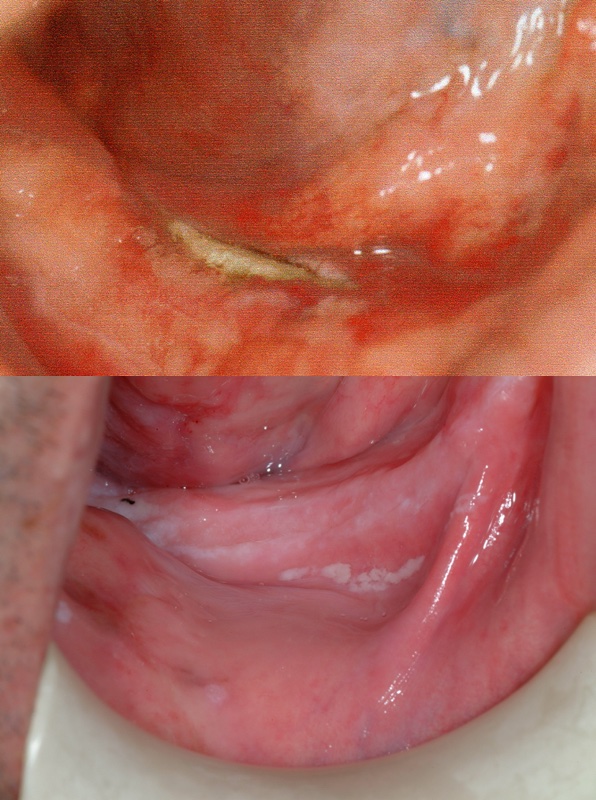

Minor, superficial surgical débridement to remove necrotic bone in some circumstances (Figure 1) may be an appropriate minimal intervention. Its success relies on the ability to achieve a ‘watertight’ seal by means of antiseptic packs, mucosa or other vascularised soft tissue. Without seal, complete mucosal healing is unlikely.

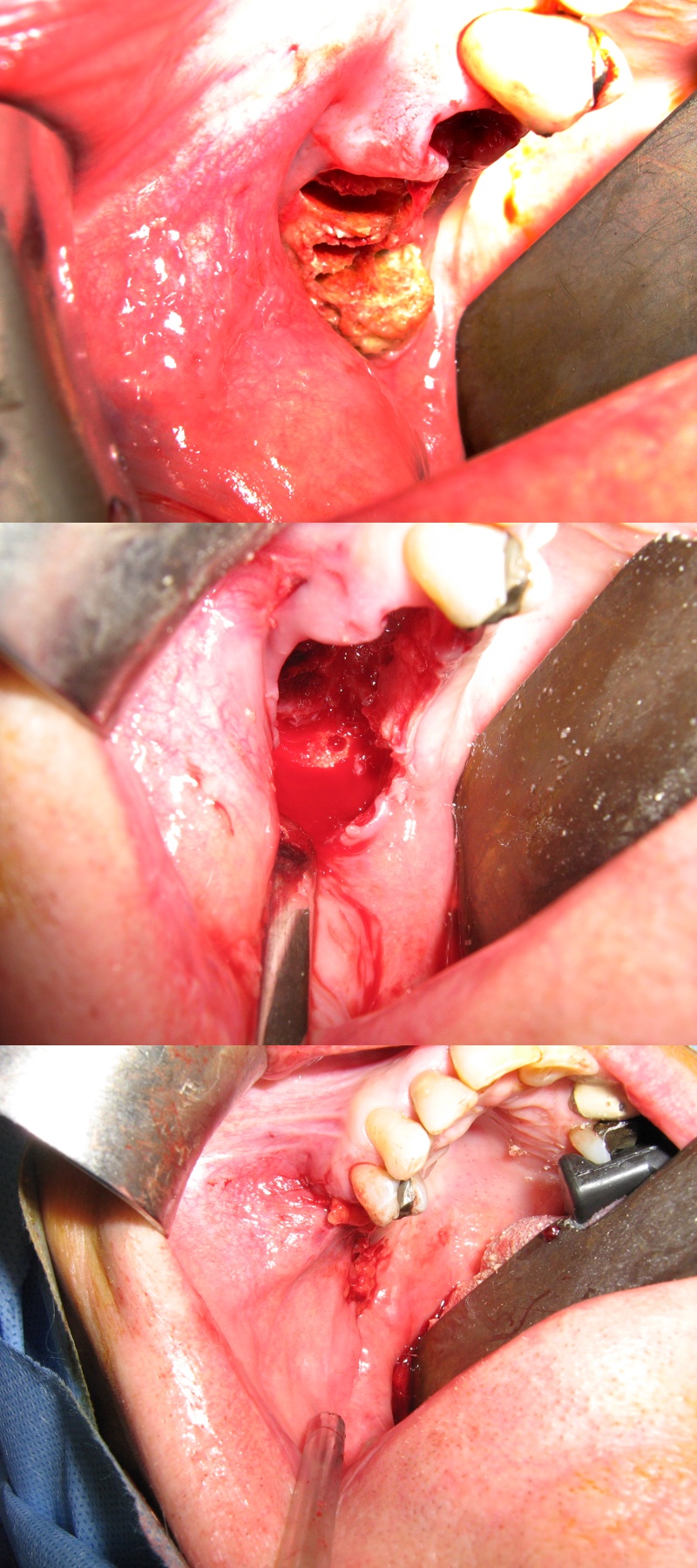

More extensive forms of ONJ require more extensive surgical strategies. These include removal of all necrotic bone (sequestrectomy), smoothing of bone edges, decortication (Figure 2). In some such cases, primary wound closure may still be possible. With increasing defects, it is more likely that vascularised local soft tissue will be needed to provide a local flap for an effective seal. Other possibilities for wound closure are regional or free soft-tissue flaps.

Extended ONJ lesions, most commonly affecting the mandible, require extensive resections where reconstruction of the resection defect by hard and / or soft tissue microvascular free flaps is necessary, especially ORN lesions (Figure 3).

Reconstruction of extended MRONJ lesions can be predominantly guided by the repair aspects of the bony defect, because MRONJ tends to affect the adjacent soft tissues to a lesser degree than ORN does. Accordingly, a single free flap chosen to cover hard and soft tissue defects will typically be the appropriate surgical strategy (Figure 4).

Reconstruction for ORN may require a combination of two different flaps. This is because the residual surrounding soft tissue contains large numbers of cells which have also sustained high-energy radiation damage and when they attempt to heal after surgery, they essentially necrose. This means that the invisible soft tissue future defect must be catered for in treatment planning for ORN. There is no benefit in having a reconstructed lining of the mouth and jaw with a (for example) free fibula flap if the skin coverage then dies. This can appear overly dramatic, but a single, large two-flap operation is often the only way to create a safe healing environment (Figure 4, Figure 5).

A typical combination of hard and soft tissue flaps are, a fibula flap to repair the hard tissue defect, plus a variety of options of soft tissue free flaps (for example, from the thigh or forearm) to address soft tissue defects. The approach increases the complexity of the surgery but can deliver optimal aesthetic and functional results.

Subsequent improvements of quality of life have been reported when ORN / MRONJ are treated with free flap mandibular reconstruction. Even in the presence of significant peripheral vascular disease, free flap reconstruction can be an option, including dental rehabilitation. In some situations, major surgical intervention may be the best option even with palliative intent.

On the other hand, some patients may be immunosuppressed or suffer from carcinomatosis (widespread metastases), both leading to prolonged and complicated wound healing, enhanced risk of flap failure, or even relapse of osteonecrosis. Also, peri-operative use of antibacterial agents needs to consider carefully any possible systemic impact of such medications, depending on the underlying condition(s) and / or other ongoing treatment(s).

Obviously, there is no straightforward treatment protocol for ONJ that would be suitable for all situations. Decisions about the best possible treatment options are a complex balancing act and need to include an individual’s prognosis, lifestyle and life circumstances, needs, desires – and the reality of what can be achieved. Below we look a little closer into these aspects.

Choice of treatment option(s)

The group of people at risk of, or suffering from, ORN or MRONJ are a heterogeneous group – as they suffer(ed) from very different underlying conditions in the first place. Optimal treatment choices for ORN / MRONJ thus cannot be considered meaningfully as separate entities from the overall condition and situation of an individual. It bears a certain aspect of tragedy that ORN / MRONJ usually are simply adverse effects of otherwise often successful treatment of head & neck malignancies or osteoporosis (of different degrees of severity). This is especially so because in many such cases the impact of severe ONJ and its treatment far exceed the impact any previous treatment for the original condition(s) may have had. It has to be said, though, that in the majority of cases the overall risk – benefit analysis tends to be in favour of treatment for osteoporosis or bone metastases with antiresorptive agents. Of course, choosing to have radiotherapy as a sole or adjunct treatment modality for head & neck malignancy is also an individual decision, but is likely to have fewer viable alternatives and will come with a higher sense of urgency.

In order to strike the right balance between over- and undertreatment of ONJ, roughly two categories of considerations play a role. There are ‘technical’ aspects (such as differences between ORN and MRONJ conditions), and equally importantly there are ‘whole system’ / individual considerations of life situation and preferences.

A short summary of clinical and pathological, ‘technical’ considerations with impact on treatment decisions includes

- presence of bone metastases and / or other ongoing malignancy definitely qualifies risk-reduction by prevention before and during malignancy treatment as the best option, sometimes the only option;

- clinically, pathological fractures, skin fistulae and trismus are more frequent with ORN, whereas dental extractions (which could be planned for before starting treatment and be avoided once treatment has started) are a more relevant factor in MRONJ;

- osteolysis (dissolution of bone) is predominant in ORN, osteosclerosis (hardening and densification of bone) in MRONJ;

- pathologically, MRONJ generally disrupts the bone architecture and organisation; ORN leads to increased fibrosis of the bone tissue;

- pathologically, ORN lesions are more homogeneous in their structures with more extensive necrosis and affect the most dense bone structures most seriously (the absorption rate of high-energy radiation is higher the denser the irradiated material is);

- pathologically, MRONJ lesions tend to be more patchy and affect often cancellous bone structures (as antiresorptive agents are incorporated into bone structures all over the body, with higher deposits into well vascularised bone structures; Figure 7);

- the viability of blood supply tends to be more severely affected in ORN than in MRONJ;

- viability of blood supply may offer an explanation for the relatively increased likelihood of success of minor local surgical interventions in MRONJ than in ORN.

As the understanding of the physiology and pathophysiology of bone remodelling, and of the exact effects of high-energy radiation and of antiresorptive agents will continue to improve and grow, so will the list above.

Beyond technical aspects, the decision-finding process of filtering out the individually best treatment option(s) includes a multitude of individual aspects.

Irrespective of all these other considerations, if someone’s life expectancy and condition are poor, the main aim of any treatment has to be best possible symptom relief with the least invasive approach.

Most, but by no means all, people suffering from head & neck malignancies and subsequently having developed ORN following radiotherapy, tend to be elderly. Although this is still numerically true at the time of writing (2019), the age changes which have come with HPV-driven oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma affecting younger people, means this generalisation applies less now than it did 5 to 10 years ago.

With a good prognosis, the preferences of somebody young for treatment of ORN may be rather different from those of somebody at more advanced age. In addition, younger people are more likely to be fit for major surgery. This should not be misread as an ageist statement, far from it; it is simply a matter of fact that the life situation of somebody say, at the beginning of a professional career is profoundly different from somebody else’s who may have been retired for 20 years. The distinction here really is not age as such, but the accompanying individual circumstances and life situations and how these may favour certain treatment options over others. Some people, almost independent of age and life situation, may also have reached a point of distinct ‘treatment fatigue’ from their previous condition(s). Individuals’ expectations about functionality and aesthetic improvements vary widely; it is important to keep a sense of realistic expectations. Part of this expectation management is a good understanding of what can be achieved, which quality of life impairments are caused by ORN and which are a result of, for example major previous surgery and hence will remain.

The situation for those afflicted by MRONJ is basically a tale of two worlds. There are those who suffer from osteoporosis of variable degrees of severity, are otherwise relatively fit and have no other major co-morbidities, and are on long-term treatment with bisphosphonates, and some unfortunate invasive dental treatment, such as a tooth extraction, triggered the development of MRONJ. This is likely to be a group of people with relatively good prognoses and life expectancies, factors which will impact individual decisions regarding willingness to undergo major surgical interventions (see above). The life situation is quite different if somebody suffers from severe osteoporosis, is very frail and possibly has other morbidities, making a decision in favour of major surgery for MRONJ treatment less likely.

And there are those on treatment with a range of antiresorptive medications in order to manage and mitigate the effects of bone metastases. In many such circumstances major surgery may not by the first choice, and alternative local tissue coverage after débridement of necrotic bone may be more suitable than microvascular free-flap reconstruction, but there will be rare cases where major surgery with palliative intent is the best option. Life expectancy, overall fitness and quality of life are likely to be the most important considerations here.

Prevention strategies and adjunctive treatments

Prevention strategies

As far as ORN is concerned, better appreciation of the extent and seriousness of the condition by those who deliver radiotherapy may be a good step in the right direction. Improved appreciation would hopefully remove a major obstacle to prevention by motivating improved delivery protocols to minimise ORN risks at this stage. The role of a specialist in restorative dentistry as part of the multidisciplinary treatment team has been well established in most developed countries. The crux of the problem at the prevention stage is predicting the longevity of a dentition in any individual who may undergo radiotherapy. It is vital to avoid a sense of nihilism (remove all suspect teeth prior to radiotherapy – this may decrease the local incidence of ORN but is hardly in keeping with improving quality of life). Equally the ‘take a chance on healing’ approach inducted into most modern dentists is completely inappropriate in this instance. It really does require a specialist with experience in this area.

For all types of ONJ, ORN as well as MRONJ, awareness of risks and prevention strategies by dentists and patients is of prime importance. This includes knowledge of signs & symptoms so that at least any emerging problems can be addressed promptly / early. The ‘prevention by knowledge’ strategy extends to those clinicians who prescribe antiresorptive medications, they need to fully explain the long-term risks associated with these medications.

‘Drug holidays’ have been proposed for bisphosphonate and denusomab antiresorptives when invasive dental treatment is planned in order to minimise MRONJ risks. This may be a useful option for denusomab, which is usually eliminated from the body approximately 6 months after cessation of treatment. In the light of the very long persistence of bisphosphonates in bone (up to 15 years), common sense suggests that a short interruption of taking these drugs does not make sense. There is no hard evidence about the potential benefits of ‘drug holidays’ for bisphosphonates. It also needs to be kept in mind that a balanced decision has to be made about the overall risks and benefits of interrupting this kind of long-term medication.

Self-help is a powerful ally in the life-long prevention of developing ONJ. It goes without saying, meticulous daily oral hygiene is a crucial prevention approach (also with respect to xerostomia (dry mouth) problems following radiotherapy applied to the head & neck region, and keeping in mind the potential role of periodontal disease as one of the contributing factors in the development of ONJ). Regular visits to the dentist and the help of a dental hygienist are included, accepting a little help to help oneself.

Avoiding any potential irritants that may trigger ONJ by hurting the oral mucosa is a lifelong task for those at risk of ORN, and at least a long-term consideration for those at risk of MRONJ. Such irritants range from toothbrushes with sharp bristles (use ultrasoft toothbrushes instead), to hard foods (classical examples being crisps or crispbread; if in doubt – do not eat it), to ever so slightly ill-fitting dentures. The lifelong risk of injury to the oral mucosa is particularly high after radiotherapy, which leaves the mucosa permanently vulnerable.

Any of the mentioned self-care actions are well worth the effort if they can help to avoid ONJ, or at least slow down the progression of the condition.

Adjunct treatments

Hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) treatment schemes have long been advocated by some as an adjunct option for the treatment for ORN, or as a preventative measure to avoid the development of ORN after invasive dental treatments, following radiotherapy to the head and neck region. There has never been convincing evidence for the efficacy of the approach and finally, the HOPON trial has demonstrated that the approach is useless. Fortunately, the trial also showed that (as one might have reasons to fear, given the cell-toxicity of free radicals) that at least HBO does not trigger or drive recurrence of malignancy.

In some sense, also the PENTOCLO medication scheme (see above) may be seen, and has been used, as an adjunct treatment option. There are no randomised prospective clinical trials, NICE has recommended its use only as part of clinical trials and frankly, the rationale for use has serious limitations. The desperation of both patients and clinicians in wishing to avoid or treat both forms of jaw necrosis perhaps explains some of the wishful thinking that seems to drive these approaches.